Book Review: “The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer” by Alessandra Sanguinetti

By Rafael Soldi | November 24, 2020

Published by MACK

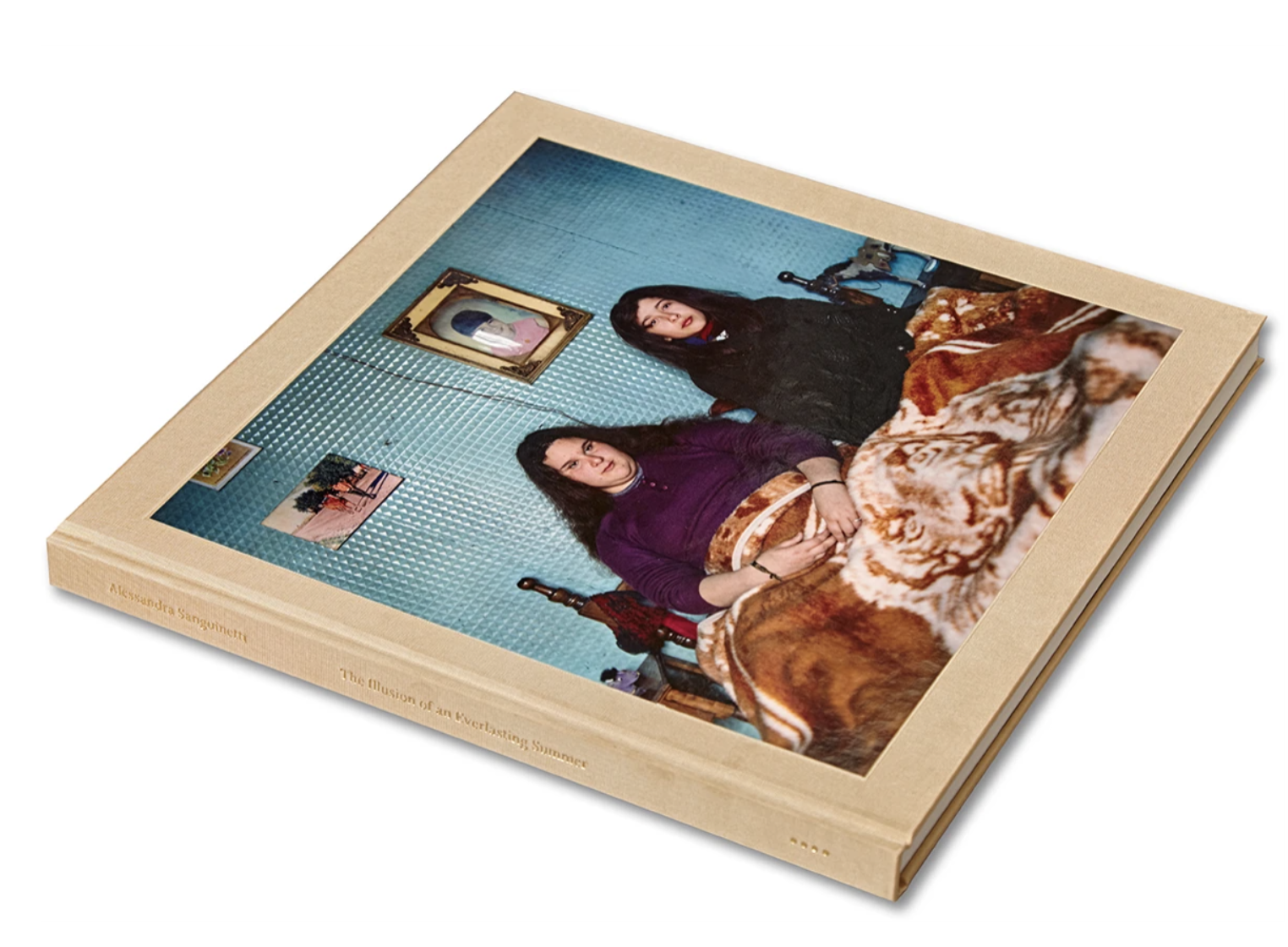

11 x 11 in | 144 pages | Embossed silk linen hardcover with tipped-in image

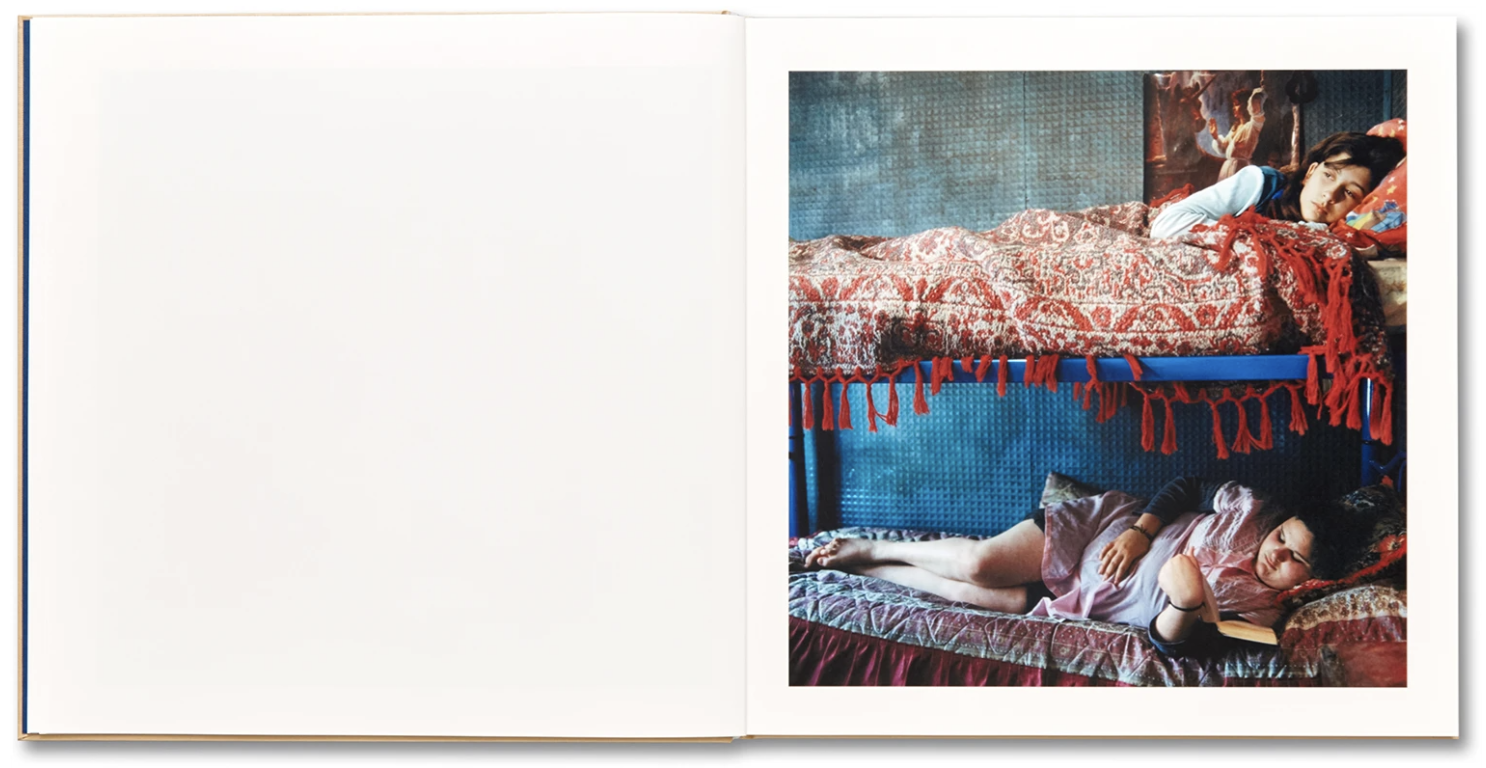

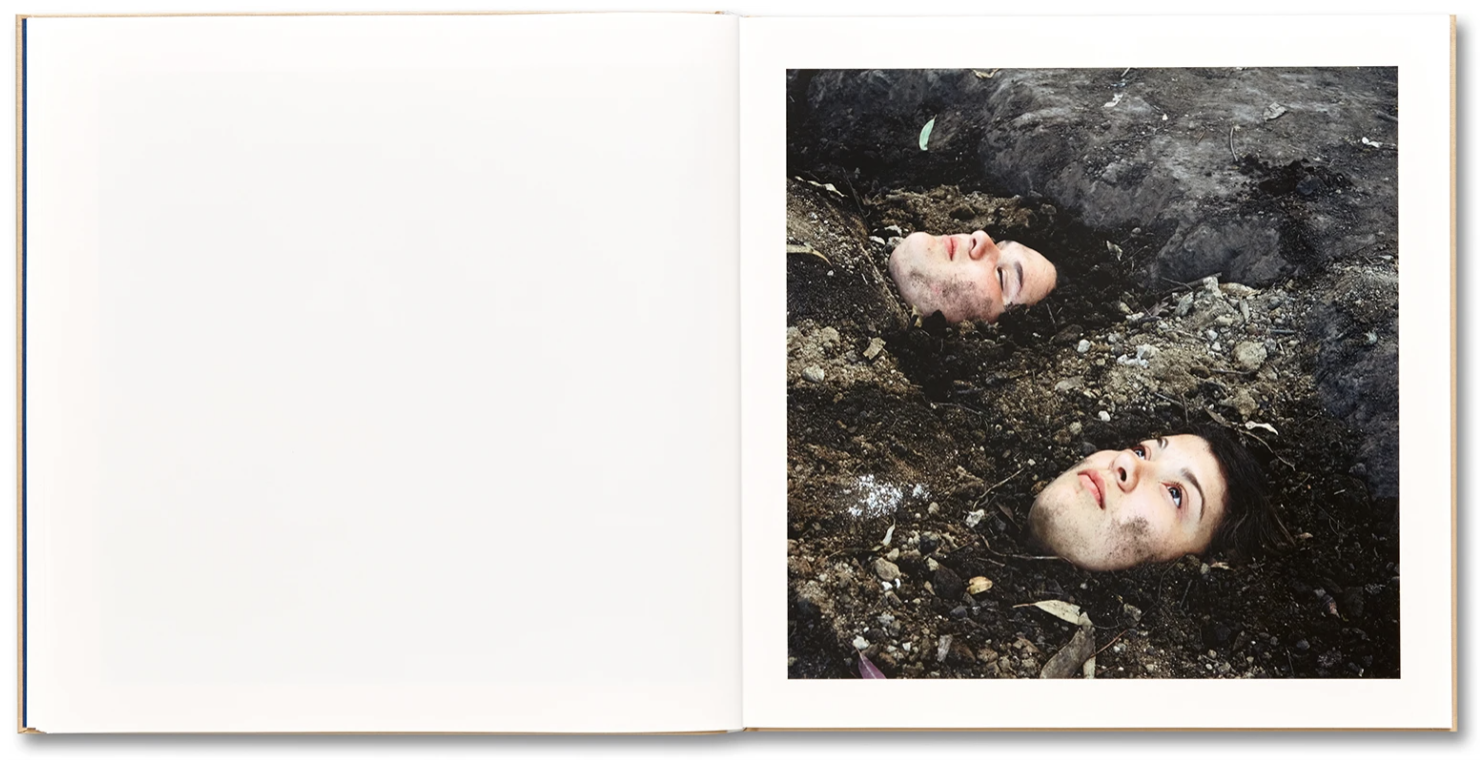

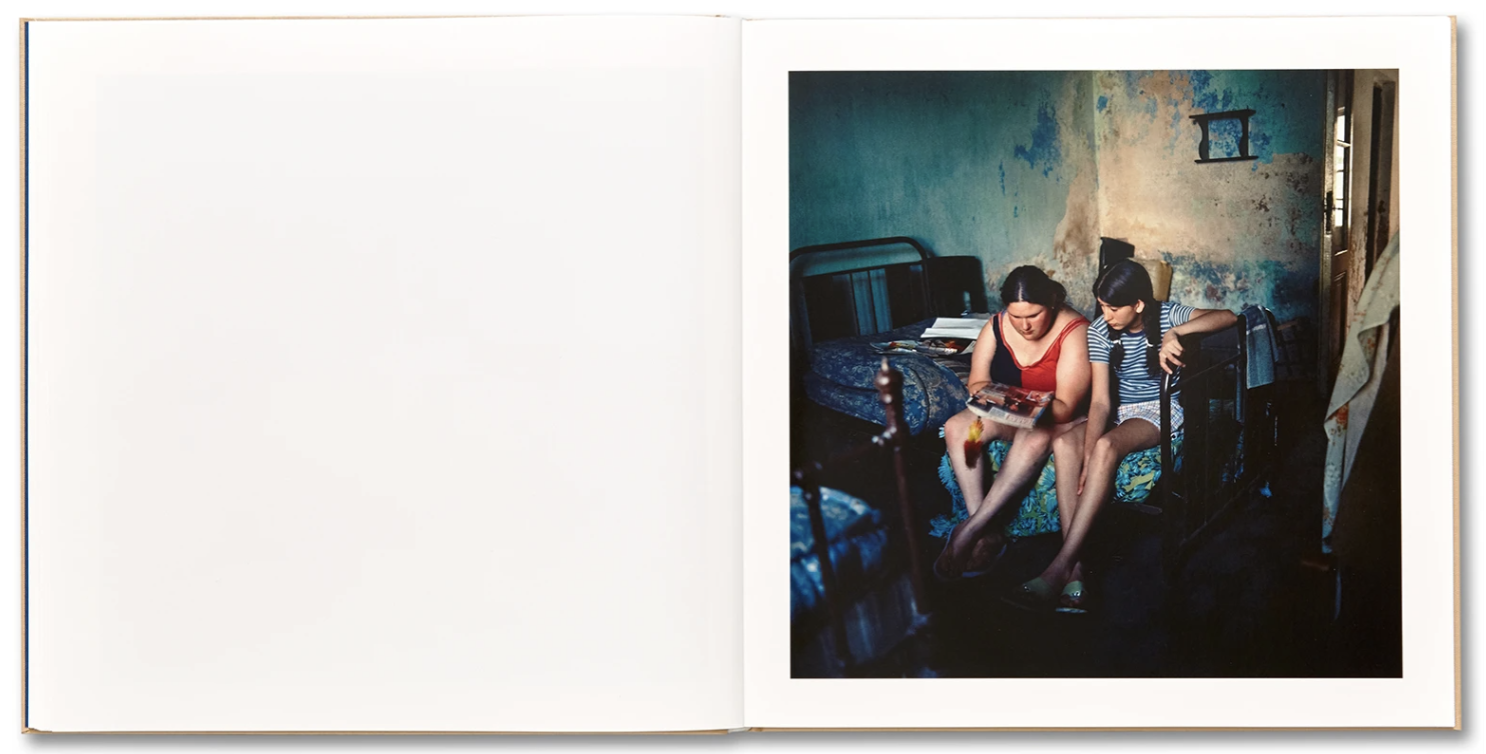

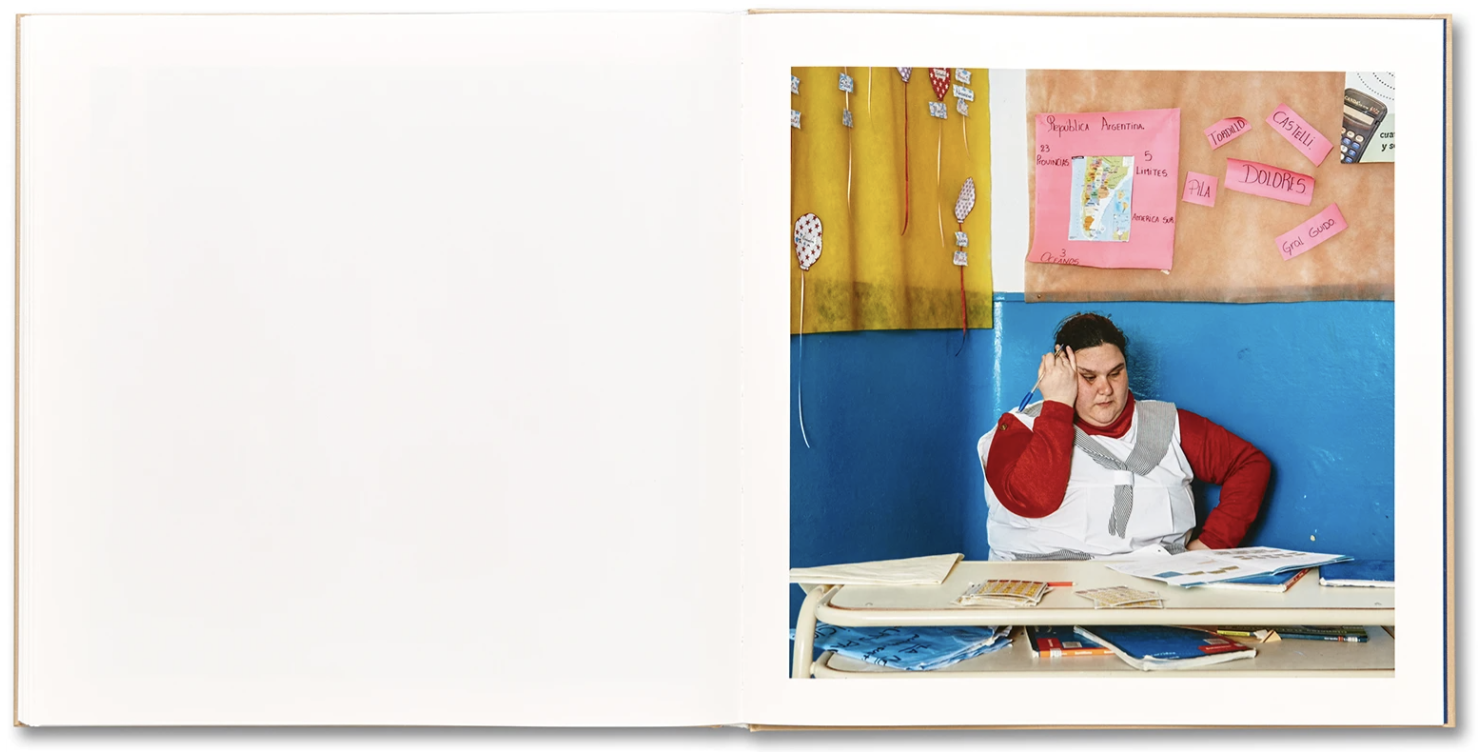

Alessandra Sanguinetti’s The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer (MACK) comes a decade after her 2009 The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and the Enigmatic Meaning of Their Dreams (Nazareli Press / Yossi Milo Gallery). It’s impossible to write about this book without also diving into the first one, for they are both part of one story. Both books are the same size and format—square, cloth-wrapped, with a large tipped-in photograph on the cover. In both, the cover image is a portrait of Belinda and Guille, cousins and the subject of Sanguinetti’s lens since the late 90s. “I started taking pictures of Guille and Belinda in 1999,” writes Sanguinetti, “when they were nine years old. We would pretend we were on a TV show and I would film them while they interviewed each other. They’d dance and sing and ask each other about their favorite fruit or animal or singer. I would whisper to them my own questions.” Sanguinetti’s photographs indeed feel like whispers—quiet interventions into a world that feels otherwise already fueled by fantasy. In The Ilusion of an Everlasting Summer we see Guille and Belinda quickly grow from young girls to young women, their playful imagination confronted by the realities of domestic work and motherhood. We see their bodies change and their faces carry newfound expressions of wisdom, pain, worry and exhaustion. There is, however, still a persistent atmosphere of whimsy mediated by Sanguinetti’s lens.

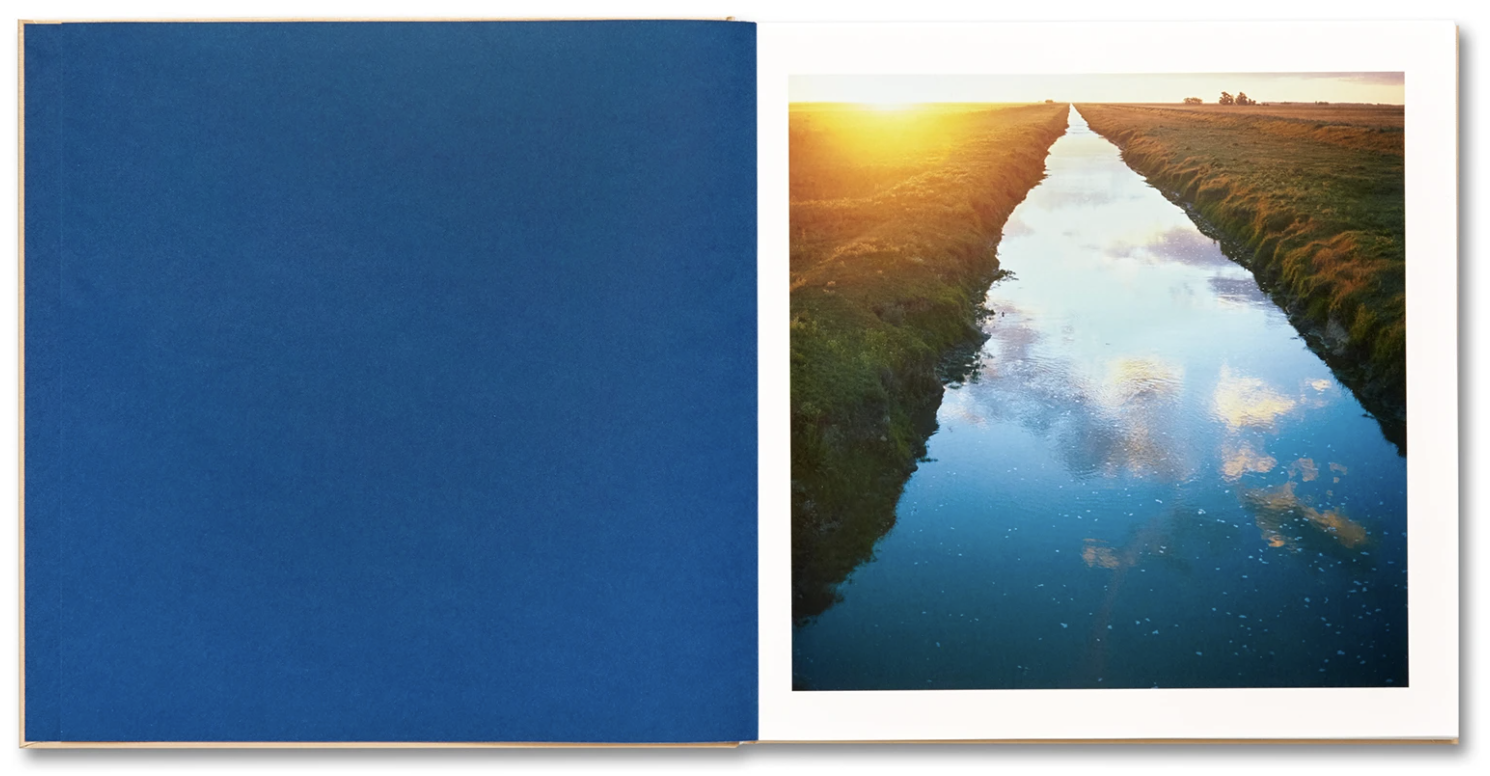

This is evident immediately as we open the book and are first met by an idyllic landscape—an infinite river mirroring an impossibly blue sky as a glowing sun buds the horizon in the distance. We know right away that we are in a place unlike any other. On the next page one encounters young Guille and Belinda crouching at the water’s edge, their reflections crystallized on the surface against the deep blue sky. Notably, the image is upside-down so that their reflection is right-side-up. Sanguinetti’s decision to prioritize their reflected selves—as opposed to their flesh and blood—legitimizes imagination in a world—the farm—entrenched in the realities of sentient life and death. It makes one ask, is this dream-space a reflection of themselves, or are they a reflection of their fanciful subconscious?

Throughout the book we see Guille and Belinda flower into womanhood, and though both shift focus to a world of responsibility, their tender connection remains palpable. In one image we see Guille placing her hands on Belinda’s pregnant belly. In another, their fingers clasp as one hands an egg to the other.

In the first book we follow Guille and Belinda while Sanguinetti works to “crystallize their rich yet fragile and unattended world”. Each image is a rich tableau where they enact a fantasy reel of weddings, pregnancies, motherhood, and other scenarios. A decade later, we bear witness to the theatre colliding with the realities of rural daily life. Sanguinetti captures these moments with the same clarity and dignity that she brought to the earlier, more lighthearted days. Two photographs in particular jump out to me. There is a photograph in the first book titled The Couple, which portrays the two young girls embracing, holding one hand in front, with the other arm wrapped around each other. Guille’s back is to the camera, she is facing away in her underwear and bra. Belinda stares directly into the lens—grounded and erect, shirtless, with dark pants and a dark mustache, clearly playing the role of the man in this fictitious couple. Her lanky body is softly embraced by Guille’s larger one. In the second book we find an image almost identical in composition. This time “the man” is Belinda’s partner, a lanky man with dark hair, shirtless, wearing dark pants—eerily similar to the man she once portrayed as a child. They also hold one hand while the other is wrapped around him. Belinda’s gaze remains aimed at the lens, while her partner looks away as Guille once did. Moments like this bring these two books into beautiful synchrony.

Left: Alessandra Sanguinetti, The Couple. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 1999.

Right: Alessandra Sanguinetti, from The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer

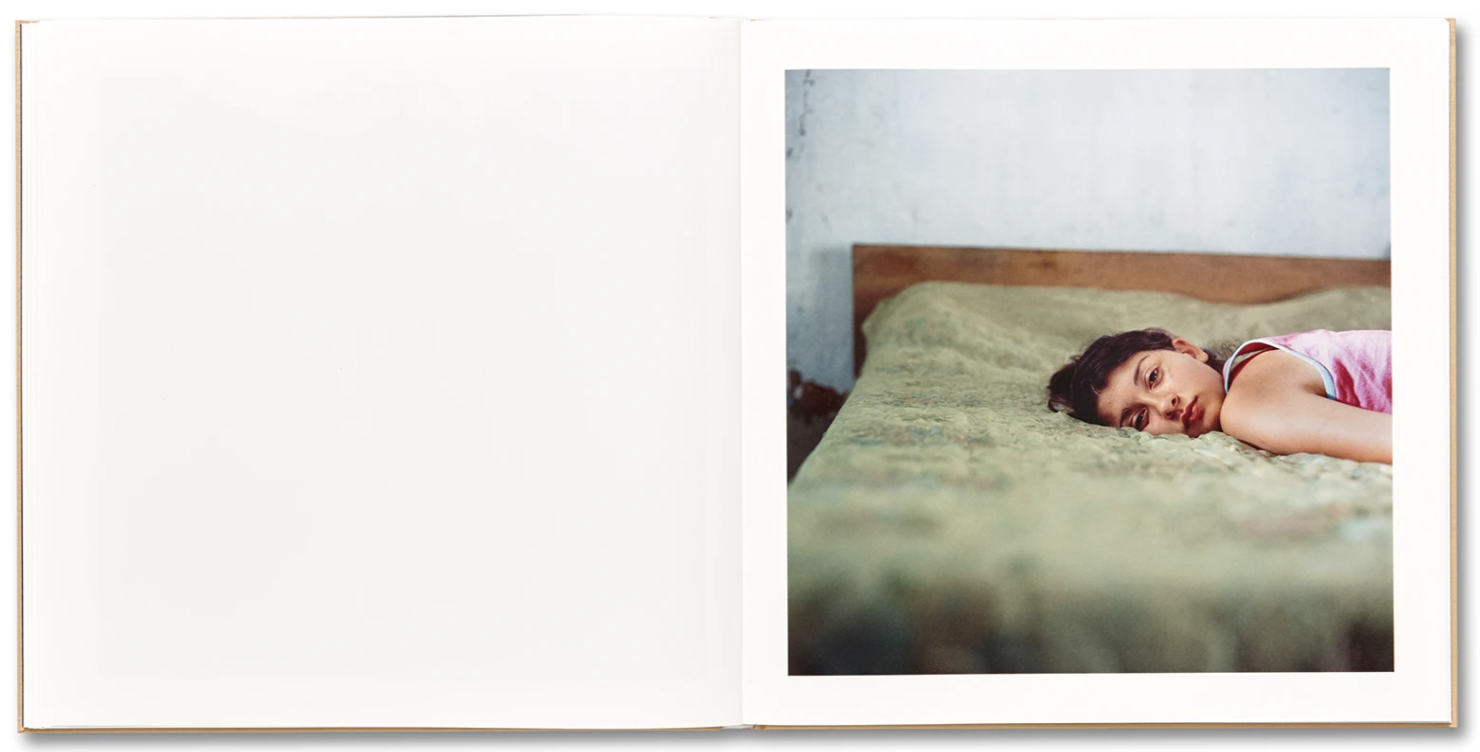

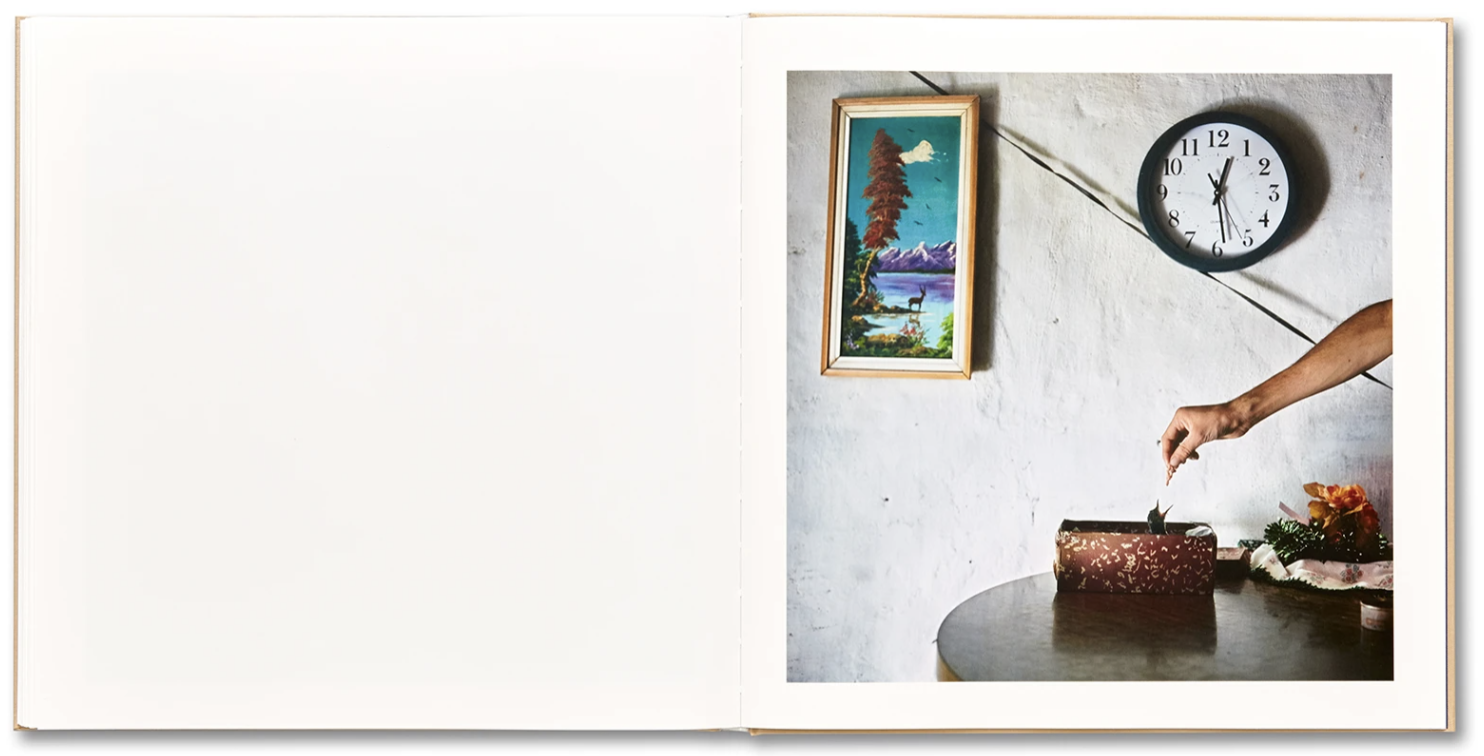

The Enigmatic Meaning of their Dreams was a more energetic book, from beginning to end, full of playful imagination and adventure. The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer begins in the same way, but quickly grows quiet. The everlasting summer is an illusion indeed, and long evenings playing with animals in the farm turn into long days of breastfeeding, working, cooking, and tending to adult life. This second book slows down and we shift to mostly seeing Guille or Belinda photographed on their own, seldom together. Sanguinetti also introduces landscapes, interior moments, and still lifes that help viewers transition from the enigmatic world of childhood fantasy to the quiet rumble of adult life on the farm.

The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer is as masterful as its prequel—Sanguinetti’s vision remains unique and steadfast, and her commitment to a lifelong relationship with her subjects rewards us with an intimate and human glance into the extraordinary imagination of two ordinary women.