Q&A: Katie Knight Curator of Speaking Volumes: Transforming Hate

From the Speaking Volumes: Transforming Hate website:

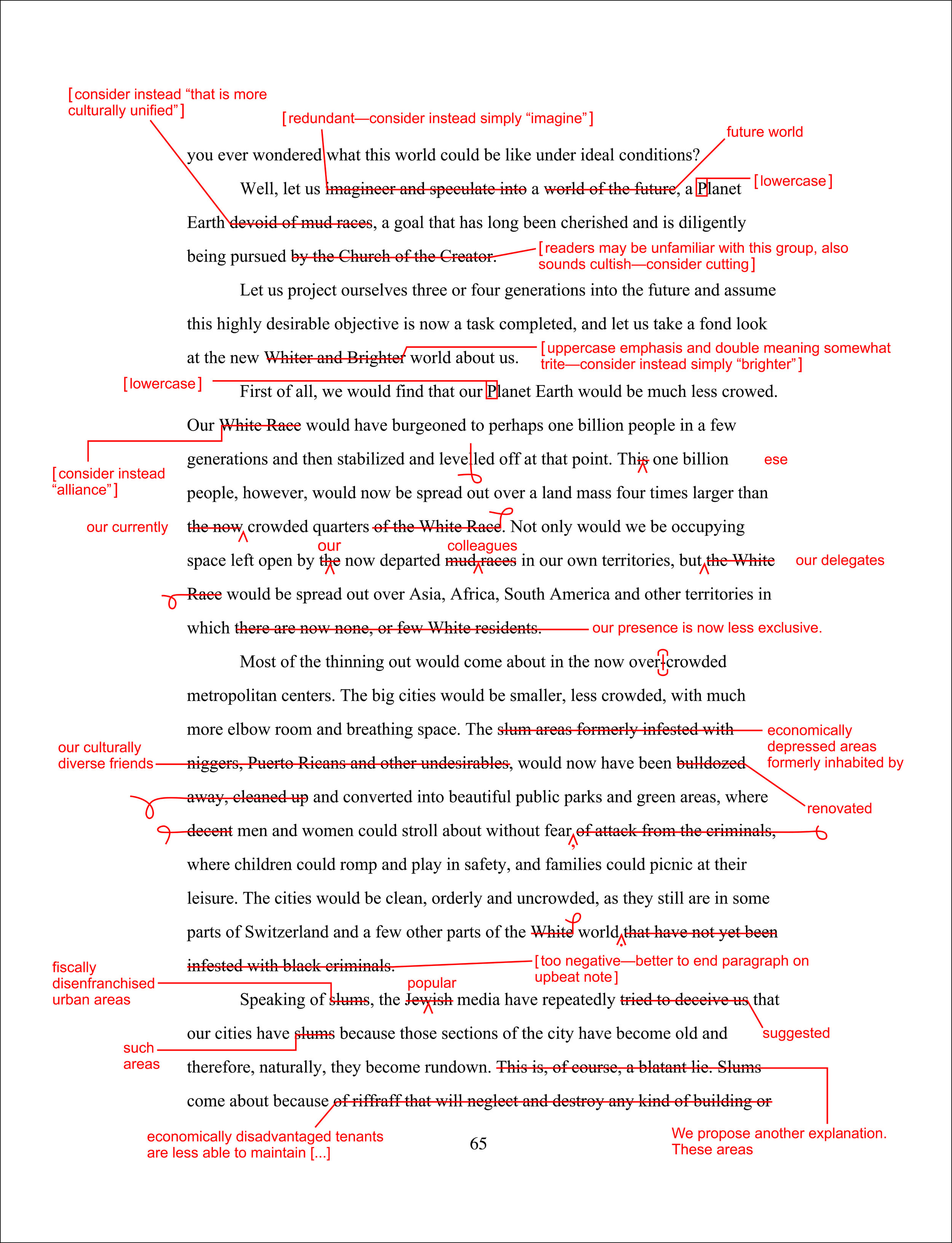

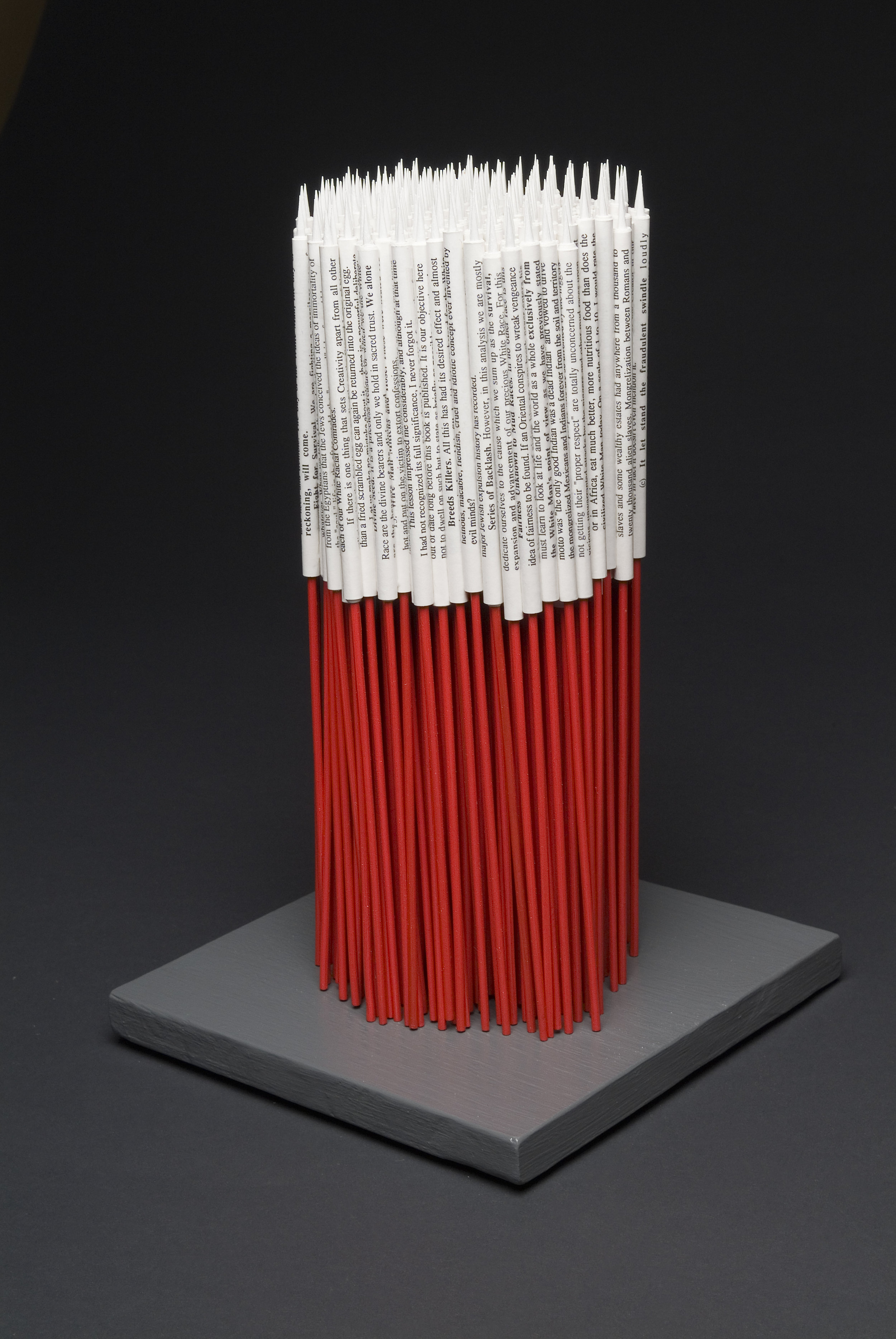

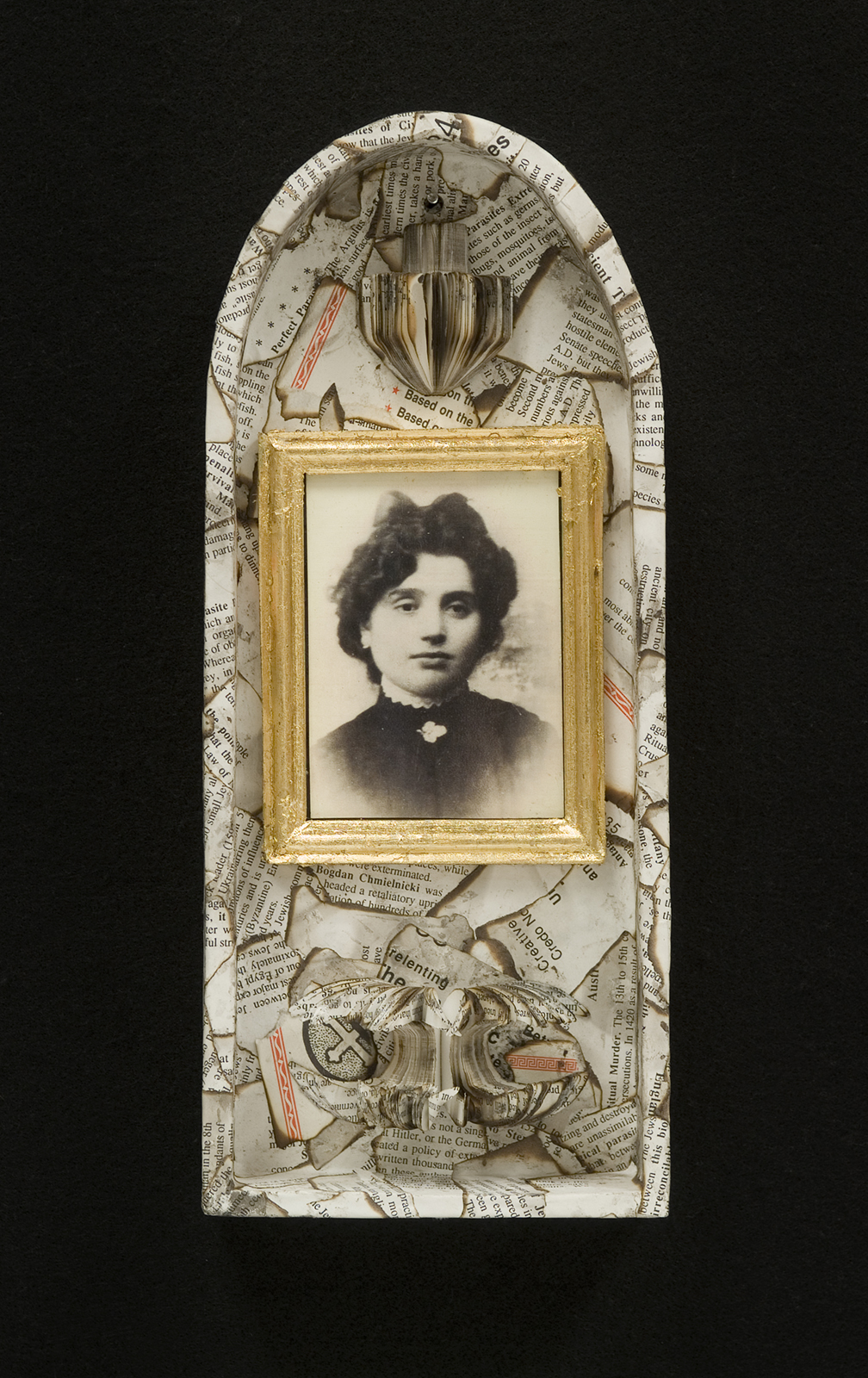

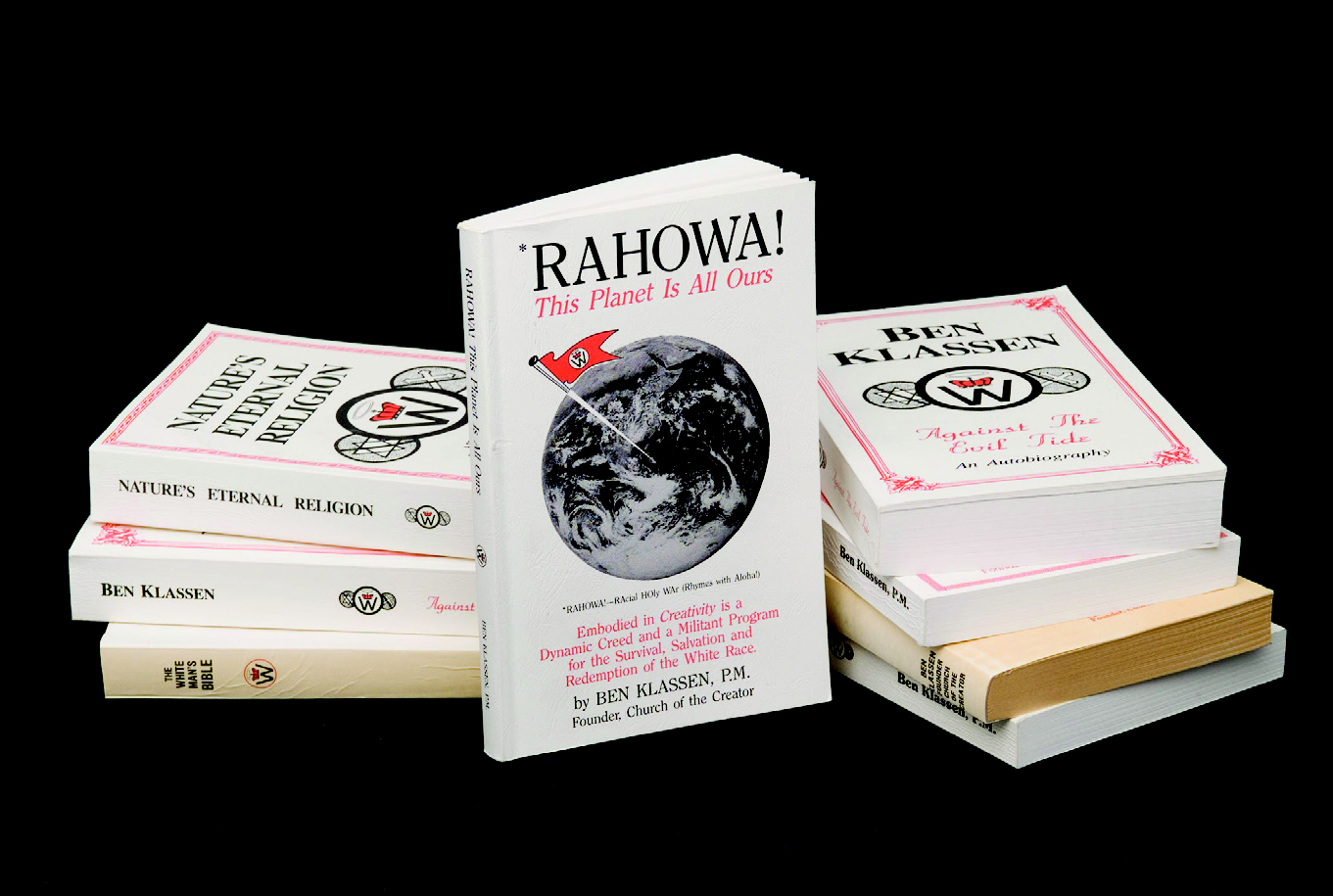

"A rare opportunity for transformation arose in Montana in 2004. A defecting leader of the “Creativity Movement” – one of the most virulent white supremacist hate groups in the nation – presented the Montana Human Rights Network with 4000 volumes of their “bibles,” books promoting extreme anti-Semitic, anti-Christian, racist ideologies.

In partnership with the Network, the Holter Museum of Art invited artists across the country to respond to, integrate, or transform the books in provocative ways. Work by sixty artists was featured in the resulting exhibition, Speaking Volumes: Transforming Hate, which opened at the Holter Museum in Helena, Montana, in 2008.

We have all been socialized to both subtle and overt forms of prejudice that contribute to attitudes of fear and mistrust and restrict our capacity to more fully experience the world. While the rapid rise in the number of hate groups and hate crimes is a cause for alarm, so is institutionalized discrimination. Systemic oppression broadly impacts members of many groups based on their race, religion, gender, sexual identity, country of origin, disabilities, economic class, and age. By responding creatively to hate, injustice and violence, the artists in Speaking Volumes provoke thinking and conversations that encourage empathy for others and respect for social justice."

These artworks are currently on exhibition at The Lincoln Center Gallery and the Fort Collins Museum of Art. I was fortunate to see the works, acquire a catalog of the initial exhibition, and meet both the curator, Katie Knight, and a participating artist, Lisa Jarrett. _Hamidah Glasgow

By Hamidah Glasgow | January 26, 2017

Curatorial Vision

by Katie Knight

(adapted from the longer curatorial essay in the exhibition catalogue)

Cruelty often reflects underlying fear and unmet needs. Might hate be disarmed by meeting needs and relieving fears? The world as we know it would be transformed if we had the insight, skills, and motivation to turn negative expressions into positive influences.

The artists participating in Speaking Volumes: Transforming Hate embraced this challenge in multidimensional forms when they converted white supremacist propaganda into art. The books in their original form represent the most extreme forms of racist, anti-Semitic, anti-Christian, and homophobic thought: yet we are all vulnerable to beliefs that diminish people who seem different. Most of us have been socialized to both subtle and overt forms of prejudice, which restrict our capacity to understand the world and contribute to attitudes of fear and distrust. By responding creatively to hate, injustice, and violence, the artists in this exhibition encourage empathy for others and respect for social justice. As curator of the exhibition, it is an honor and inspiration to work with them as they share their perspectives, ranging from grief to celebration.

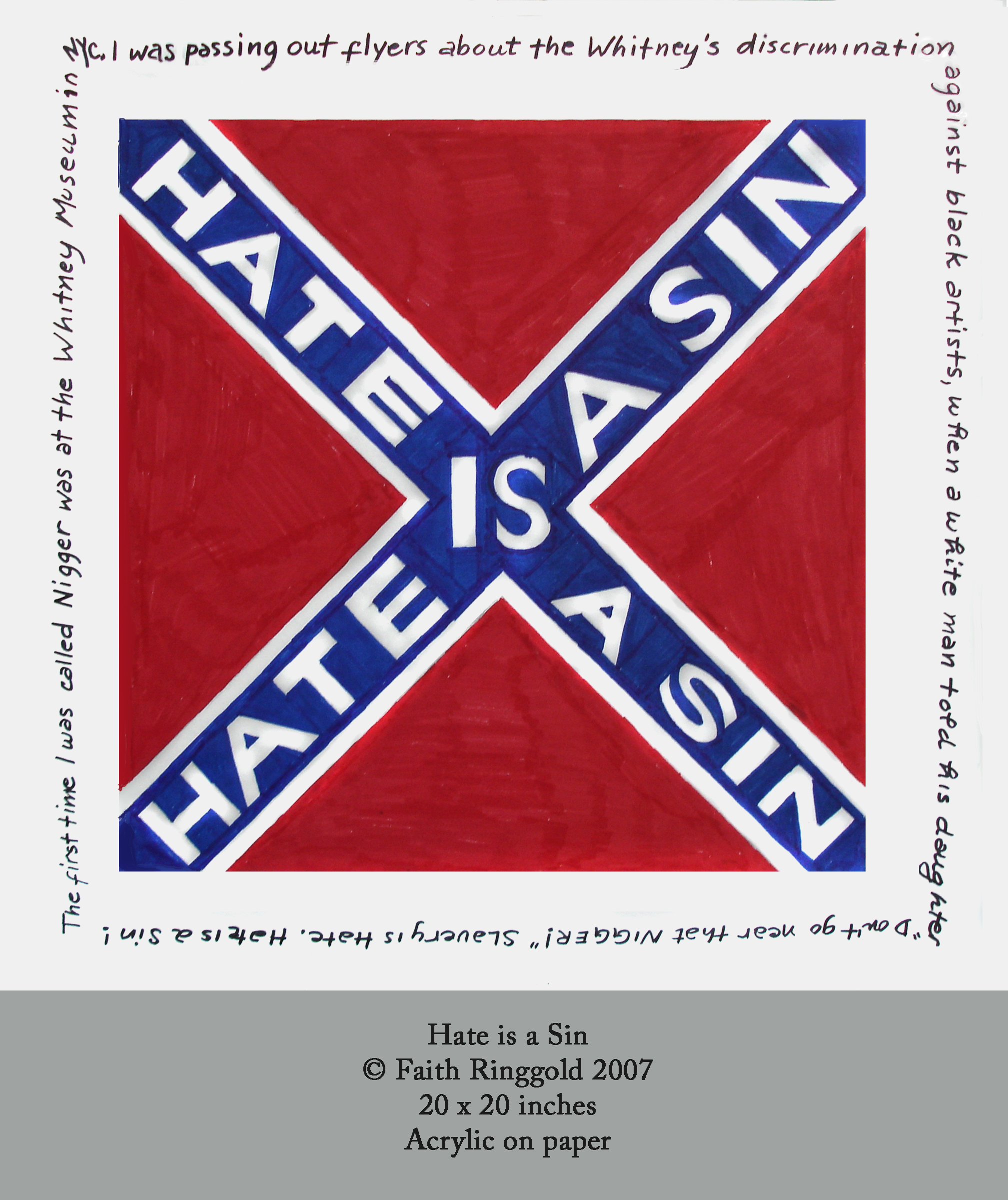

Not all of the artists reshaped the physical material and content of the books. Some chose not to handle the books directly but contributed relevant selections from large bodies of work developed throughout their careers. Many of these artists are pioneers in the use of art as civic dialogue; they have focused on issues of social justice for decades. It is a joy to include their work, which has shaped the collective understanding of the power of art. The work of these individuals has deepened our sensitivity to subtlety and irony while exploring the complexities of equality, race, gender, and beauty.

Historically, visual art, literature, music, theater, and dance have all challenged audiences with interpretations of social issues as artists reflect upon their times, comment upon contemporary problems, or envision solutions. The power of art in public dialogue lies in its capacity to arouse our passions, make us more conscious of emotional experiences, stimulate thoughtful analysis, and draw us into communication about ideas. Encountering works of art gives us shared experiences as a foundation for discussion. Even with all the communication media that surrounds us, all the chatter of daily life, it is not every day that we are invited to engage in deeper conversations about how we live together as human beings.

HG: Given that the exhibition was first shown in 2008, what if any are the differences in how you see/experience the work and the exhibition now in the current political climate?

KK: Issues addressed by this art have become even more urgent since the exhibition opened in 2008! “From the margins to the mainstream” describes the phenomenon of fringe ideas taking hold among a growing population; in this case, overtly racist actions have erupted, and we have seen surge in the number of hate crimes and hate-driven organizations since the recent election. The new president of the USA publicly demonstrates attitudes of racism, anti-Semitism, homophobia, and misogyny, encouraging others to act in ways that are inconsistent with the values of inclusiveness and justice enshrined in our constitution. I do not believe the majority of US citizens are bigots, thus it is vital that we continue to act to defend human rights. We must express our indignation and work toward ending discrimination of all kinds. The Speaking Volumes: Transforming Hate project seeks to stimulate dialogues, education, and understanding, and ultimately motivate us to action on behalf of social justice.

Nick Cave created an assemblage sculpture he titled “Profiling,” in which a stereotypical figure of a Black man surrounded by darts is displayed above a dartboard and a national map. This reference to the controversial law enforcement practice takes on intensified meaning in the context of recent killings of African Americans. This piece triggers powerful responses for me even though I am intimately familiar with it. Seeing the work anew in this context, I am reminded of an incident that occurred when my own biracial son was walking innocently in a white neighborhood of Johanesburg with his father, a Black man. They were angrily accosted by two police officers and one of them held a gun against my son’s head while accusing him of robbery. My son survived, but many have not.

HG: Are there certain works in the exhibition that have taken on deeper meaning over time?

KK: All of the works of art in this exhibition have become more meaningful to me as a result of showing them for nine years, interacting with all of the artists, and engaging with audiences from around the country. Each work has its story, a history of moving people and eliciting responses.

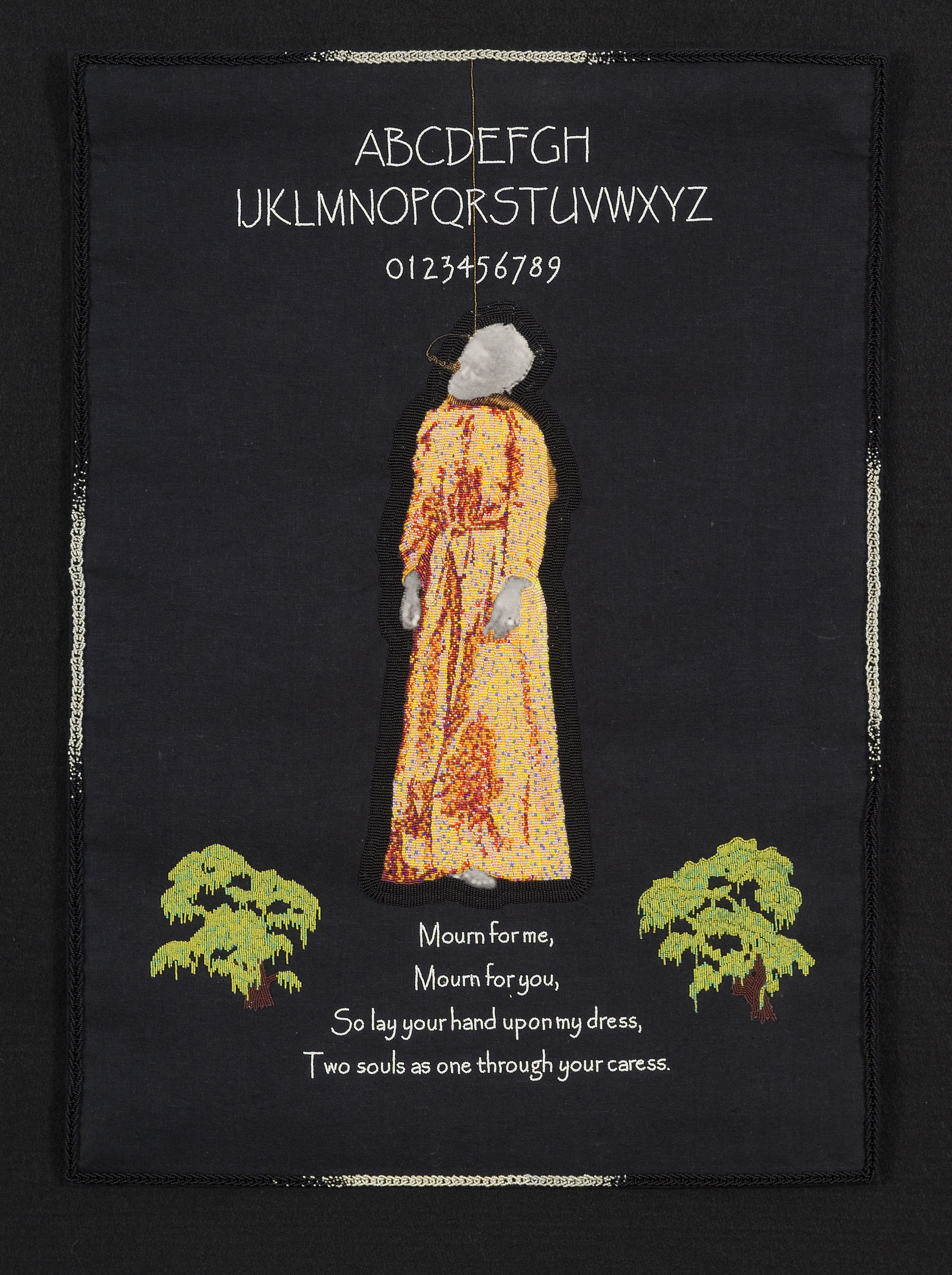

One example is Unbound, by Scott Schult, a beadwork figure of a woman on black cloth with text, has a composition that references early American colonial-era mourning samplers, the kind embroidered to remember a loved one who has died. As soon as I first unwrapped this piece in 2007, it made me cry because the figure hangs from a noose. Her photocopied face reveals that she is African American. Scott’s submission included some details about the original incident in which Laura Nelson was hanged in 1911 in Okemos, Oklahoma. When the exhibition traveled to Living Arts, a spacious gallery in Tulsa, Oklahoma, I learned so much more.

Tulsa residents are keenly aware of the local history of racial violence. Living Arts is located on the grounds of a massacre in which 300 or more African Americans were intentionally slaughtered by an angry white mob. Racism and resentment of the thriving business community known as Black Wall Street led to looting, widespread arson, fire bombing, shooting of those who fled, and the incarceration of male survivors. Thirty-seven blocks containing 1000 homes and businesses were destroyed in the conflagration. Still referred to as the “Tulsa Race Riot,” insurance coverage of the destroyed property was made unavailable by calling it a riot. Although the city sought to block reconstruction, the African American community pooled their resources and rebuilt. Next door to Living Arts is the John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park, a monument to history, tragedy, hope, and resilience.

Okemos, Oklahoma is not too far away, and is the hometown of one of Tulsa’s favorite sons, Woody Guthrie. It turns out that Woody’s father was among the White townspeople who proudly posed with the bodies of Laura Nelson and her son as they dangled from the steel bridge over the river. Woody wrote a very poignant song in the voice of Laura Nelson, Don’t Kill My Baby and My Son. Divergent reports about this incident serve as part of a history lesson on the Oklahoma State website.

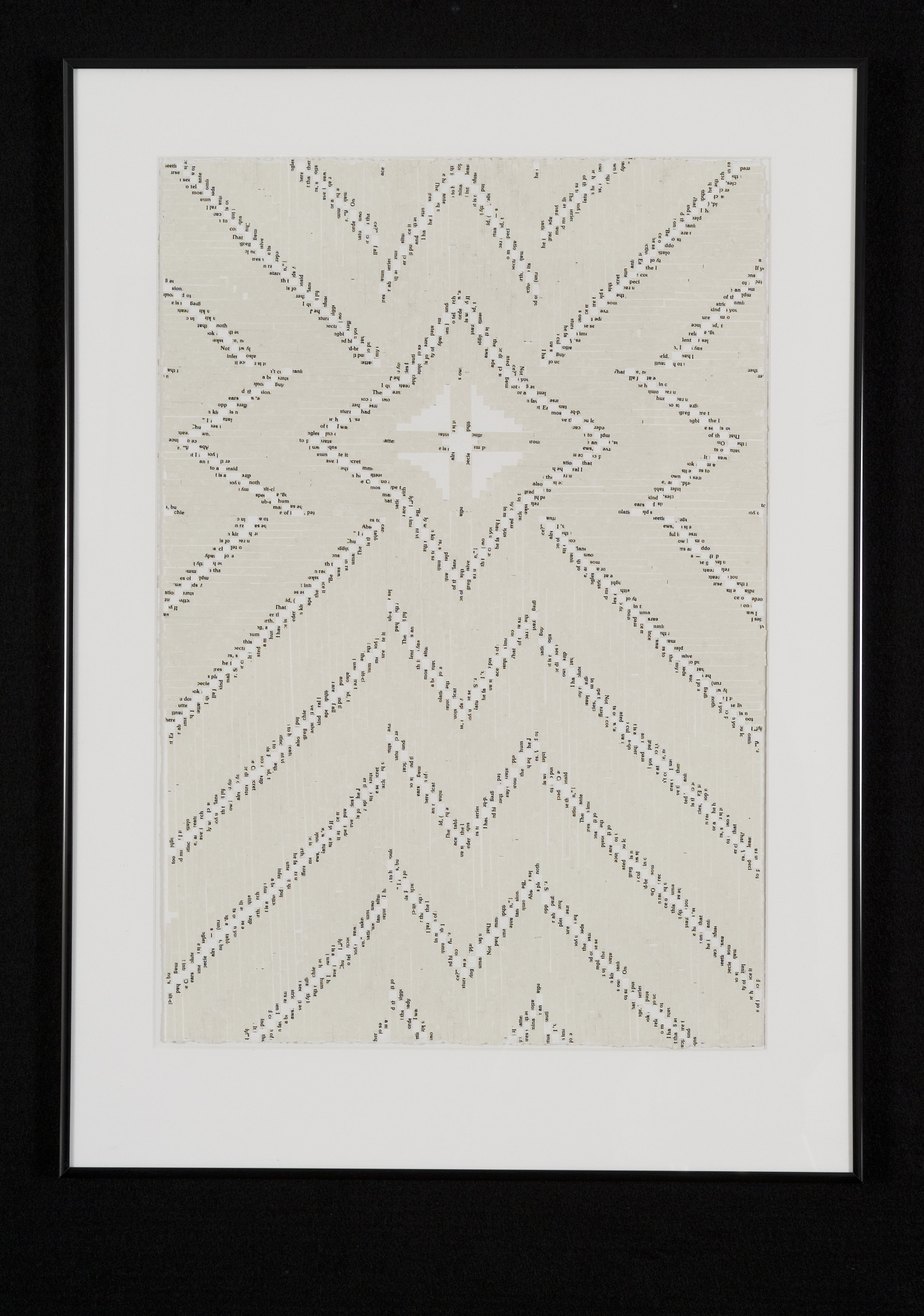

Laura Nelson’s image also appears in Lisa Jarrett’s triptych, In Equality. Her series of drawings on large panels covered with book pages include poems using words selected from the books. While the drawings are haunting, the poems offer hope. Lisa designed a poetry-writing activity for gallery visitors. Writing materials and pages from The White Man’s Bible accompany her triptych. In the nine years this art has toured, many people have constructed their own moving poems, turning hateful messages into calls for creativity and inclusion.

HG: During your curator talk at the Lincoln Center Gallery, you mentioned that your focus when talking about racism now is the institutionalized racism of the prison industrial complex. Is this something that has changed over the period of time that you have been involved in this exhibition?

KK: The prison-industrial complex took over the role of slavery as a system designed to control socially disadvantaged peoples and exploit their labor. The escalating numbers of prisoners, the privatization of prisons, and the criminalization of poverty are deeply disturbing trends. These interconnected issues demonstrate graphic evidence of institutionalized racism and classism. This is documented in the new film, 13th, which is visible online.

HG: What happened to the white supremacist books that were left over after the artists had finished? If they are still around have you thought about inviting new artists to make work based on these books?

KK: The Montana Human Rights Network was eager to clear their offices of the 4100 books, the situation which originally motivated this project. They were very relieved when a mother-daughter team collected all of the remaining books and used them to construct a house. Dana Boussard and Ariana-Boussard Reifel built a small house titled Hate Begins at Home. That work appeared in three Montana venues but is too large for the current national tour. However, the performance piece designed for the house interior is on tour and currently being presented in the gallery.

Any artists who would like to create work inspired by this project could work from scans of pages from the books. I can provide these via the internet. In fact, I do plan to select new art for a complementary exhibition being planned for 2018.

HG: Thank you Katie for your vision and passion.

All images © the respective artists