Q&A: Sara J. Winston

By Jess T. Dugan | February 8, 2018

Sara J. Winston explores representations of sickness, wellness, and methods of care necessary to manage chronic illness, using photography and photobooks. She earned her MFA in Photography from Columbia College Chicago in 2014. Winston’s books are collected by many artists’ book libraries, including The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University and University of Michigan Artists' Book Collection in Ann Arbor, MI. Winston’s book Homesick, published with Zatara Press in 2015, was named one of the best books of 2015 by John Gossage for Photo-eye. Winston’s book, A Lick and a Promise, was released by Candor Arts September 22, 2017.

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Sara! Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me today. Let’s start at the beginning. How did you discover photography, and what was your path to deciding to use it as your primary medium?

Sara J. Winston: Hi Jess! I’m excited to be sharing some insight about my work with you and the Strange Fire Collective community.

I discovered photography at home with family when I was young. My mom had an Olympus OM-1 that she would take out and use for special family occasions like reunions and birthdays. When my brother, who is 9 years older than me, took a photography class during his junior year of high school, I was envious that he was granted use of our mother’s prized camera. I could see that the camera created a connection between photographer and subject and was curious and intrigued to experience this myself. Following in my brothers footsteps 9 years later, I took the same photography course with the same teacher and was immediately enchanted with the medium.

I decided that I wanted to pursue studying photojournalism, and was fortunate to be accepted to a school in Washington, DC, the former Corcoran College of Art + Design. One semester into my studies on the photojournalism track, I realized I wanted to use photography in more introspective and experimental ways and that I wanted to become a master of analog b&w and chromogenic printing; things that were not central to the curriculum in the Photojournalism arm of the Photography program. I transferred into the Fine Art Photography concentration and my world was transformed. We had a lot of independence in the program as well as really dedicated faculty. It felt like a family. Many of my classmates and professors who helped me develop my sense of color and composition are still my closest friends.

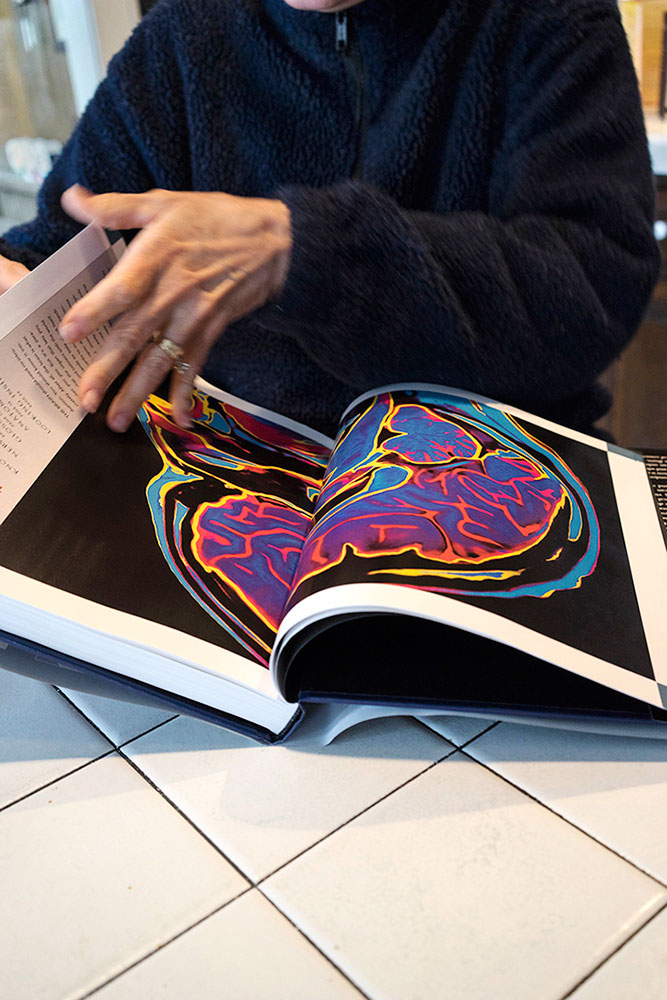

From A Lick and a Promise

JTD: Tell me about your recent project, A Lick and a Promise. How did it come to be and what would you identify as the underlying theme?

SJW: I began photographing A Lick and a Promise in 2015 when my partner and I were living with my parents in rural New York. We had just uprooted our lives in Hamtramck, Michigan so I could receive care and family support while managing my first severe Multiple Sclerosis relapse. I had been documenting throughout the move and afterward, out of necessity to metabolize the experience. I was learning more about my parents, including that despite the 40 years that separated our age, we share similar symptoms. I began to think I was creating a documentary project about intergenerational illness within a family, specifically as it exists within my family, and how the shared experience of illness can create tighter kinship between relatives.

From A Lick and a Promise

When I got to the stage of editing and sequencing the images for a book, I realized, because of the nature of the edit I had selected, this iteration of the work had become something different than I intended. Rather than being about intergenerational illness, A Lick and a Promise had become a visualization of a shared sense of care between parent and child. I had asked my father to write a short essay for the book project, and I don’t think I realized what the work had become on a conscious level until my father shared his completed manuscript. In his writing, he says “A parent always feels that he or she should be the first line of protection for a child, protecting from all of life’s evils and ills... Nothing is more destructive to one’s protective instinct than a health problem of a loved one. The feeling of impotency is indescribable. I have come to realize that if I want to live long enough to share in the future of all my loved ones, I need to take better care of myself, something that before was unfortunately, quite low on my list of priorities.”

From A Lick and a Promise

JTD: Your photographs themselves are quite varied in content, ranging from pictures of people to organic objects, such as plants, to rather banal objects that exist within the domestic space. Throughout these images, there is a certain kind of unifying poetry or visual language that unites them, yet what exactly that is would be hard to put into words. What is it that draws you to photograph particular people or objects, and how do you ultimately decide what to include in your finished works? What is your own editing criteria, if you will?

SJW: I’ve always been fascinated by the visible mark objects leave on the world and the many readings that material culture can convey about human activity or emotion. I think that is what drives me to document such a range of things. When I’m photographing, I’m looking for that kind of trace evidence in my surroundings, but taking extreme care to make a formal photograph, like making a portrait of the object. In that regard, I’ve been influenced by the work of Stephen Shore and William Eggleston.

I’m really interested in my photographs working the way idioms do in verbal communication. In the past few years of managing Multiple Sclerosis with doctors, I’ve realized that I rely heavily on idioms and similes to describe experiences and sensations of my symptoms. There isn’t more concise language to describe what a filleted leg feels like without invoking that language. I’m attempting to do the same with my photographs. It isn't that I wish to romanticize the experience of illness, but more that I'm tired of medical jargon or failures of language to describe indefinite management.

Portraits became important around 2014 at the tail end of my work Homesick. Before then I wasn’t interested in incorporating portraiture. That changed when I started making work about my family’s experience of illness.

Front and Back Cover of Homesick , published with Zatara Press, Richmond, VA, 2015

JTD: I imagine it must be both difficult and cathartic to make work about chronic illness, particularly when focusing on yourself and your family. What has your experience been making this work? What has been particularly challenging, or conversely, particularly rewarding?

SJW: It has been all those things: cathartic, difficult, rewarding. Making this work has been a combination of research, photographing, and opening myself up. I'm reading this fascinating book, The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing & The Human Condition by Arthur Kleinman, MD of Psychiatry. In the first chapter he works to clarify the language frequently used throughout his text to distinguish the nuanced differences between illness, disease, and sickness: illness as the human experience of symptoms and suffering, disease as the problem or deviation that, from the practitioners' perspective, needs biomedical treatment, and sickness invoking the understanding of disorders in relation to macro social forces.

The work I’m referring to in this interview began when I was experiencing my worst MS exacerbation. I needed a lot of help to get well and photographing throughout that period helped me remain grounded. Photographic documentation was the one thing that didn’t change before or after I became sick. When my symptoms became less of a physical distraction, I began to think of the photographs I was making as work I would publish.

Spread from Homesick, published with Zatara Press, Richmond, VA, 2015

When Homesick was published as a book in 2015, I wasn’t ready to be open about what the visual diary I had created was about; my relocation and the experience of loss and vulnerability that were the result of illness. I wanted to create that feeling through my images without overtly describing my own sense of loss and healing.

Photographing with my family is fun. It has brought us closer. There’s a lot of joy in it. It has been important to respect my family’s limits and always represent them respectfully. At the start of my Homesick work, my father said as long as I wasn’t displaying his genitals nothing was off limits to photograph. This remains the cardinal rule. My mother has become very good at ignoring the camera and embracing me as if the camera is a natural extension of my hand. My partner is so patient when I’m photographing him. I try to continue to check in because boundaries are dynamic.

From A Lick and a Promise

JTD: Although the photography world is large and varied, it seems to me that we are only relatively recently entering a time period where very personal work, specifically work about family, domestic space, illness, women, motherhood, or any number of other things, is being taken seriously. What has the reception been to your work? Have you experienced any pushback because of the content? Or, do you think the moment I described has passed, and today it is a non-issue?

SJW: The reception has been more positive and welcoming than I imagined. I’ve been thrilled and humbled by recent acquisitions of my books to libraries such as the Haas Family Art Library at Yale University and Emory University’s Artists’ Book Collection. When I’ve talked publicly about the work, earlier this year in Chicago during Filter Festival and in Pittsburgh during the Silver Eye Book Fair, the exchange of empathy between the audience and myself has been incredibly positive and powerful.

Although we all experience it, illness is very difficult to talk about. The lack of visibility and awareness of chronic illness in particular is a site of crisis. The experience of illness and care is different than it appears on dramatized medical shows. I’ve found that my story of chronic illness can have a universal reach, and in some cases, empower others to tell their own stories.

Any pushback I’ve received has only empowered me to work harder and keep making my work. I believe personal stories about illness need to be told in order to construct a stronger foundation of awareness of the vast range, impact, and realities of debilitating chronic disease. It feels particularly prescient in the current state of our political climate, when the future of health insurance that guarantees those of us with “pre-existing conditions” reasonable coverage may no longer be required by law.

I don’t think the moment you described in your question has passed. I think too often topics like illness, motherhood, domesticity are regarded as “feminine,” which to me has strong derogatory connotations. Many important artists have put a lot of work into leveling the field, but we still have work to do.

A Lick and a Promise, published with Candor Arts, Chicago, IL, 2017

JTD: You have made several artist books, including Worn Out Joy (2011), Flowers for Ruth (2014), Homesick (2015), and most recently A Lick and a Promise, published by Candor Arts in 2017. This last book in particular is an incredibly beautiful object. What draws you to working with artist books? When do you decide a project is ready to publish as a book, and what is your process for going from individual photographs to the book form?

SJW: Part of why I choose to make books is because of my own love for book objects. I’m a collector, a reader, a writer, and a book maker. When I’m editing my photographs, I’m almost always doing so with a book form in mind. I love the intimacy of reading a book. I like that reading isn’t a passive act. When an artist book works, and form and content are aligned, the object really demands the mind’s engagement. One of my favorite contemporary examples of this is Rinko Kawauchi and Terri Weifenbach’s book Gift; a book of photographic correspondence between the two artists published as a conjoined double book, read right to left on one side and left to right on the other, making it possible to read in Japanese or English sequence, or both simultaneously.

I make my photographs to be strong as singular images. In a book sequence I can piece together an intimate narrative and use the visual idioms I’ve created to tell a story of the range of care, loss, and unpredictability of living. My editing criteria is intuitive. I rely on formal characteristics within the images, like shape and color, but also the emotional tone of an image. I think of photographs like words in a sentence that create meaning and narrative when they’re woven together. The photographs themselves are as important as the space between them.

I’m committed to each book being a chapter of a larger series. I’m still figuring out the scope of that series. That’s part of the fun.

Text spread from A Lick and a Promise, published with Candor Arts, Chicago, IL, 2017

JTD: What are you currently working on, and what is on the horizon for you as an artist?

SJW: I currently have several irons on the fire, many of which I cannot discuss yet.

I’m working on making a strong exhibition proposal for Homesick and A Lick and a Promise to be exhibited in a gallery setting side by side. I’m really excited by the idea of seeing that work exist in that context outside of a bound book. I’m busy working on putting together an edit of work I made of the plants of the Detroit Public Library Main Branch, work that I began in 2014 that is ongoing. I’m hoping to go back to Detroit to visit and photograph at the library again soon. Recently I rediscovered an article published about my father in The New York Times in 1988. I’m working through how that article might become a part of a book project I'm working on, titled The Passing Measures. Overall I’m very excited for 2018!

Thanks again for taking the time and asking such thoughtful questions, Jess. It has been a pleasure.