Q&A: Sakura Kelley

By Zora J Murff | Published October 20th, 2016

Sakura Kelley was born in San Diego, California. She received her BA from University of California, Santa Cruz, where she studied Art and Community Studies. After graduating she went on to pursue her work in Japan through a series of residencies, including at BankArt 1929 and Hammerhead Studios. Kelley has exhibited works both domestically and internationally, including galleries in San Francisco (CA), Providence (RI), Quezon City (Philippines), and Yokohama (Japan). Sakura Kelley is currently pursuing an MFA in photography at Rhode Island School of Design where she is continuing her scholarship around queerness, feminism and art.

I first met Sakura at last year's National Society for Photographic Education conference in Las Vegas where I had the pleasure of seeing her talk about her series Bury Your Gaze. Throughout the weekend, we were able to have brief (but enjoyable) conversations about our work and graduate programs. For this week's feature, Sakura and I continue those brief conversations we had in Nevada, touching on the ideas of labels, activism, access, and her work.

ZJM: How did you get into community studies?

SK: It turns out I’ve always been someone who has been in between things, whether that’s mediums or genres. In undergrad, to be perfectly honest, I wasn’t set out to do art necessarily. I had good grades in art classes, and figured that by writing that I was majoring in art was an effective way to get in to [UC] Santa Cruz to begin with. I was always interested in art, but I wasn’t sold on the idea of being an artist or pursuing that full time, mainly because I was interested in social issues and social justice. But it was undeniable that my outlet was creative and that I was a maker, so even though it cost me an extra year to finish, I decided to double major in art and community studies.

During an internship, I went to New York and worked for a radical independent newspaper as a photographer only to prove to myself that I didn’t want to do that kind of work. They say, “don’t knock it till you try it,” and I tried it, and didn’t like it.

ZJM: Do you feel that your background in community studies informs your artistic work?

SK: I think the general interests in my ways of thinking, regardless of the major, is at the core of who I am, and therefore just guides how I move through the world and how I make the work.

ZJM: As far as social justice, do you feel that your work fits under that umbrella?

SK: Definitely not. In the most abstract way, I could say that maybe I think that for us to experience joy or pleasure or real sensations as liberating considering the social world we live in (dehumanizing/desensitizing)

If I can find my own liberation through making, maybe that could abstractly be considered under these categories. I think I was always skeptical of bringing the two together – as far as my art making and categories of social justice – especially with photography. There’s an easy link to be made there, which is why I went and photographed protests or different “lefty” things because that seemed to be the most obvious way to put my creative abilities towards my thinking or my desire to do “good” (to reference my 19-year-old self). I realized more and more that there is such a complexity in what it means to “do good,” and even especially after graduating, becoming a teacher and going to more exclusive parts of higher education and art world environments, I see that there aren’t very many people like me, so it’s actually a big deal that I’m here. This in and of itself has value in the same way that working for a non-profit or direct cause is effective; it’s just a different form. If what I make is not legibly about social justice in a didactic way, that’s okay.

ZJM: This is something that I’ve personally struggled with as well. I didn’t set out to be an “activist” or “social justice artist”, it’s a label that just gets applied. I’m not sure what I would label myself as.

SK: Yeah. If anything, I’m super stubborn and I hate to be put into categories, so in a way, I almost have this chip on my shoulder. To imply that non-majoritarian people should have to be a part of a cause or make work that is “activisty” and to make it kind of a burden is unfair. If you want to do it and that’s your thing, that’s awesome. But I know I’ve felt that I’m supposed to do that kind of work, and I’m like, “Why am I not given the same liberty to make whatever I want to like my white-male-cis-[gender]-artist counterparts?” I would say I have a radical critique or perspective which is very different from what I think of as activism, not because it’s better or worse, but because activism is really about organizers and the scheme that goes along with it.

ZJM: Is your work about Queer identity?

SK: No. Maybe this is a semantics issue. I’ve thought about this, and I like say that I make through queerness.

ZJM: Your identity becomes your own individual access point, but your work isn’t about that, right?

SK: You know, I think that by saying something is “about” something, creates the impression that one looks at the work, and the viewer should be able to download information. In general, maybe this isn’t just about queerness or identity. It’s a different paradigm of how I consider art. The viewer is impacted however they’re impacted. I make through the experiences that are my own. Felix Gonzalez-Torres is a really good example of this. Is his work about Queerness? No, but also totally, yes! That’s the model how I think about what I make and how I think about myself as an artist.

ZJM: Again, I’m having a similar struggle. I’m currently making work surrounding police brutality and stereotype and image - trying to essentially break the ideas that come from images down to its core. But it’s very much through my own interpersonal struggles and reactions to seeing police footage of someone being killed. It always comes back to idea of labeling. Am I making this work because I’m black? Well yeah, in a way I am. I wouldn’t be having these reactions, these fears, these things that I need to process through if it wasn’t for my identity.

SK: In some ways, looking back in some sot of art historical sense, there have been female artists who don’t want to be considered “women artists” because they want to just be seen as artists. I never even put the word queer near any artist statement until probably more recently, because I feared the kind of reductive discourse of “identity art”. Because, and I’m not the first to say this, it is in its own way like a ghettoizing of particular artists. But then, over the last couple of years, I’ve tried to amend this because I want to be known as a queer artist. Not because I want to be on a different shelf of the library, but because it has been so important to me to find other artists both in history and contemporarily. I have been able to do this because they have certain keywords listed next to them. When google search happens, I want these key terms to yield me to whoever is looking for me because I’m looking for them too.

ZJM: Let’s talk about access. This is a question that I get asked a a lot, “I want to make a “x” project, but I don’t feel like it’s my place to make it.” Have you had those experiences? And if so, what would be your advice?

SK: It feels encouraging that people are asking themselves and possibly others this question – parentheses – I hope that they’re not asking the members of that community because we need to stop putting more emotional labor on people. [If someone asked me] “I want to photograph queer people, do you think it’s okay?” I would be like, “Nah…I can’t do that work for you. Please don’t ask other queer people.” This is all super-nuanced stuff. Because if it was in conversation with someone I know well and they were asking me, then I would feel like it makes sense. But if someone was just asking because I’m a queer artist, it is again a reductive way of thinking about identity that is unfortunate. I’m glad that people are asking because I do think that a lot of photographers or even based in the medium’s history is a sense of entitlement that one can just innocently photograph as they please.

My most easy response is, why? I would be curious as to why they want to take these photographs. I’m trying to think of a hypothetical to model my response off of. All of the ones I can think of are deeply personal and people I know, and that’s not fair. Can you give me a scenario?

ZJM: Let’s say a student wants to make photographs at a Native American Reservation.

SK: Ok. Why do you want to take pictures of Indigenous folks? Do you have a desire to help? So on that premise, that I will take at face value, is taking a picture really helpful? How do you know that is helpful? Because if you haven’t thought about it, your opinion is likely informed by the social-colonial mentality that “I should help these helpless people”.

If we’re talking about getting them representation, do you have to take the picture then? If so, then maybe you should lend them your fancy camera. That’s self-representation and the camera is a lovely tool that’s very easy to teach people how to use. And in fact in the digital era, you probably don’t even need to teach them how to use the technology, they’re probably producing their own images now with their iPhones. So why don’t you find a publisher for that group and really promote them.

[Helping people] is typically the response, [but] I think that people like to use that rhetoric to cover – what they may not consciously know – that they want to make interesting images. And you want to make interesting images because you would like to sell them. And when you sell them, are you going to give them that money? And even if you are, is that efficient as an economic proposition? There’s a lot of basic [and] fundamental problematics built into most general curious people [, though] they’re already self-reflective in asking other people the opinion of if they should or shouldn’t.

I want to also add that just because you’re [considered] in-group is not a free pass. You’re certainly in a better position to start the project, but that doesn’t mean that we aren’t accountable to each other, that we don’t run a high risk of re-instituting internalized “whatever”. We need to redistribute responsibility. There is responsibility for that in-group member too, and you could produce something responsibly – possibly – as an out-group [member]. Otherwise it is black and white. We’re again putting more labor on the backs of people who have already been oppressed. Let’s redistribute the sense of responsibility. I hate [the narrative] of “I’m privileged, I’m a white man and there’s nothing I can do.” There’s so much you can do, you just might not get to be the savior this time, but there’s a lot of shit you can do.

ZJM: That brings us back to this idea of activism, activism versus art. Is your making helping? And what is the better approach, to make or to help?

SK: Again, the fundamental idea is, what is considered helping? And when I open up that can of worms, it is important to make note that there are different categories of actions, and if possible, I would like to think of them not as “better” or “worse”, but existing on a wider axis of ways to exist in this world. It’s like trying to do an impossible calculus on what’s considered help or what’s more effective. Over a lifetime, regardless of what type of work I make, if I can get into the position where I can mentor other artists that are people of color, queer people, and really cultivate this rising of true diversity, then that seems really important to me. But that’s an extremely nuanced thing, because how can I compare that to the work that I was doing as an intern at a radical newspaper (an action from the outside that could be considered “doing something”)? Can we compare these two? They seem like apples and oranges, entirely different categories. If anything, I do have the aspiration to be someone who can provide a model that you can be a complex person, that you don’t have to be reduced down to your hyphens of identities. I can do more than what is expected of me as a two dimensional poster version of my identities as a queer artist of color.

Maybe there’s an understanding in a different way, and that’s where materiality and affective responses have become increasingly important to me. It’s not about this intellectual understanding of data, maybe making is a way for me to transfer or infect somebody else with these experiences. Also because a lot of the things I’m interested in are not “queer”. Where do I draw the line? Is it about queerness? Is it about being a person of color? Is it about being a woman? There’s no point where I’m like, “This piece is about x”. It’s about the feeling of erasure or the instability of trying to deconstruct normative ways of thinking. What I’m interested in is not just that we do that, but the real emotional and physical impact it has on one’s body to be in that kind of state. If I can transfer that feeling of anxiety or terror to the viewer, that’s where I would consider it to be successful.

ZJM: Let's talk about your work. Can you tell me about your series, Bury Your Gaze?

The Japanese term minitsukeru describes an interconnected relationship of the experience and the body. The first character (mi) means body, the second character (tsukeru) means to join or to apply. It is used in two ways: the first use describes the action of putting something on one's body, as in clothing or jewelry; the second more abstract meaning is to acquire knowledge, to become accustomed to, or to master something such as a skill or craft. The two uses connect how familiarity is gained through the body, and conveys the tangible effect learning has on the body. What has been put on my body acts as muscle memory that directs how I use the camera and the materials I work with. I am interested in this term to anchor my approach and my logic formed by experiential knowledge carried on the body.

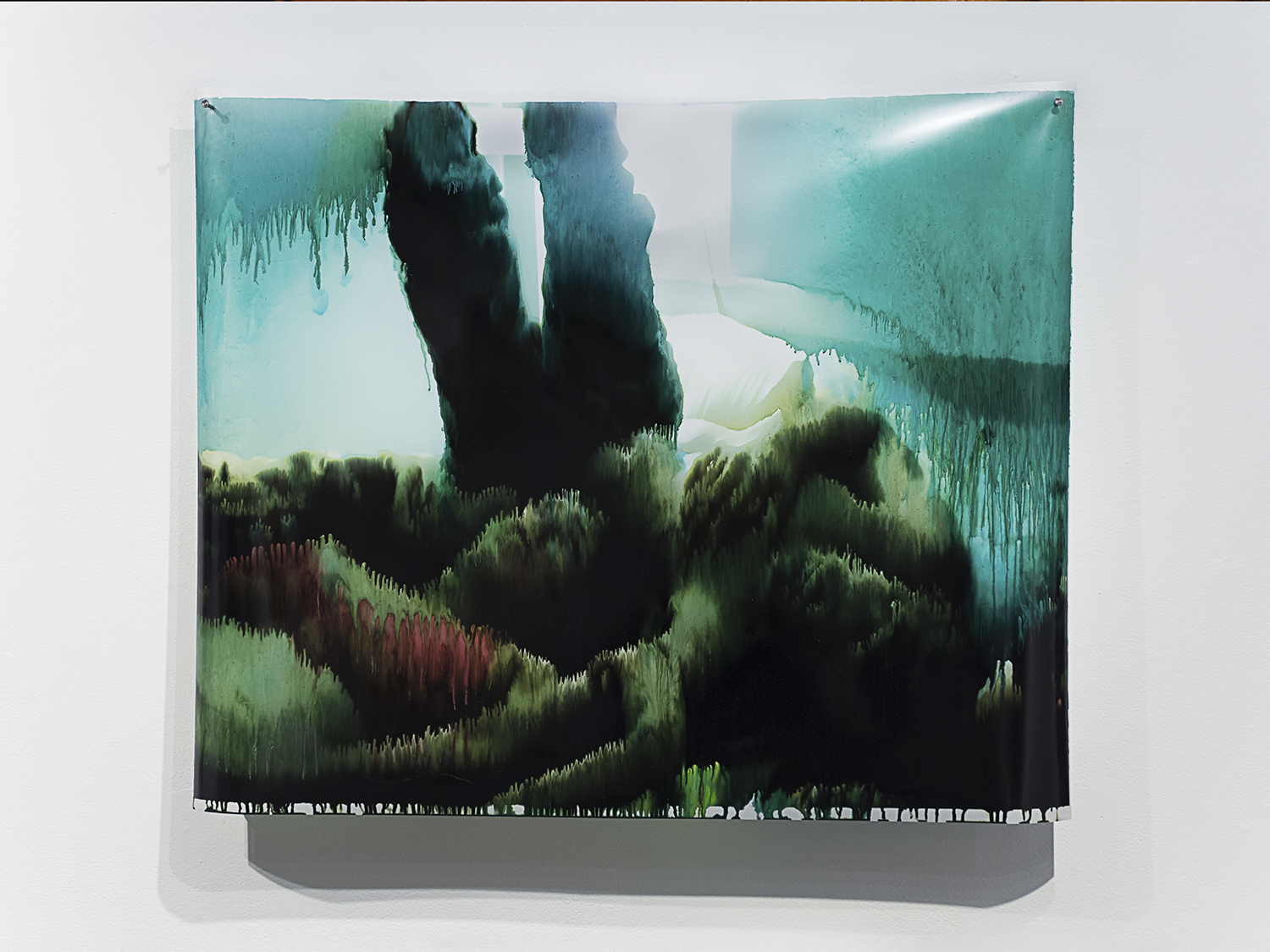

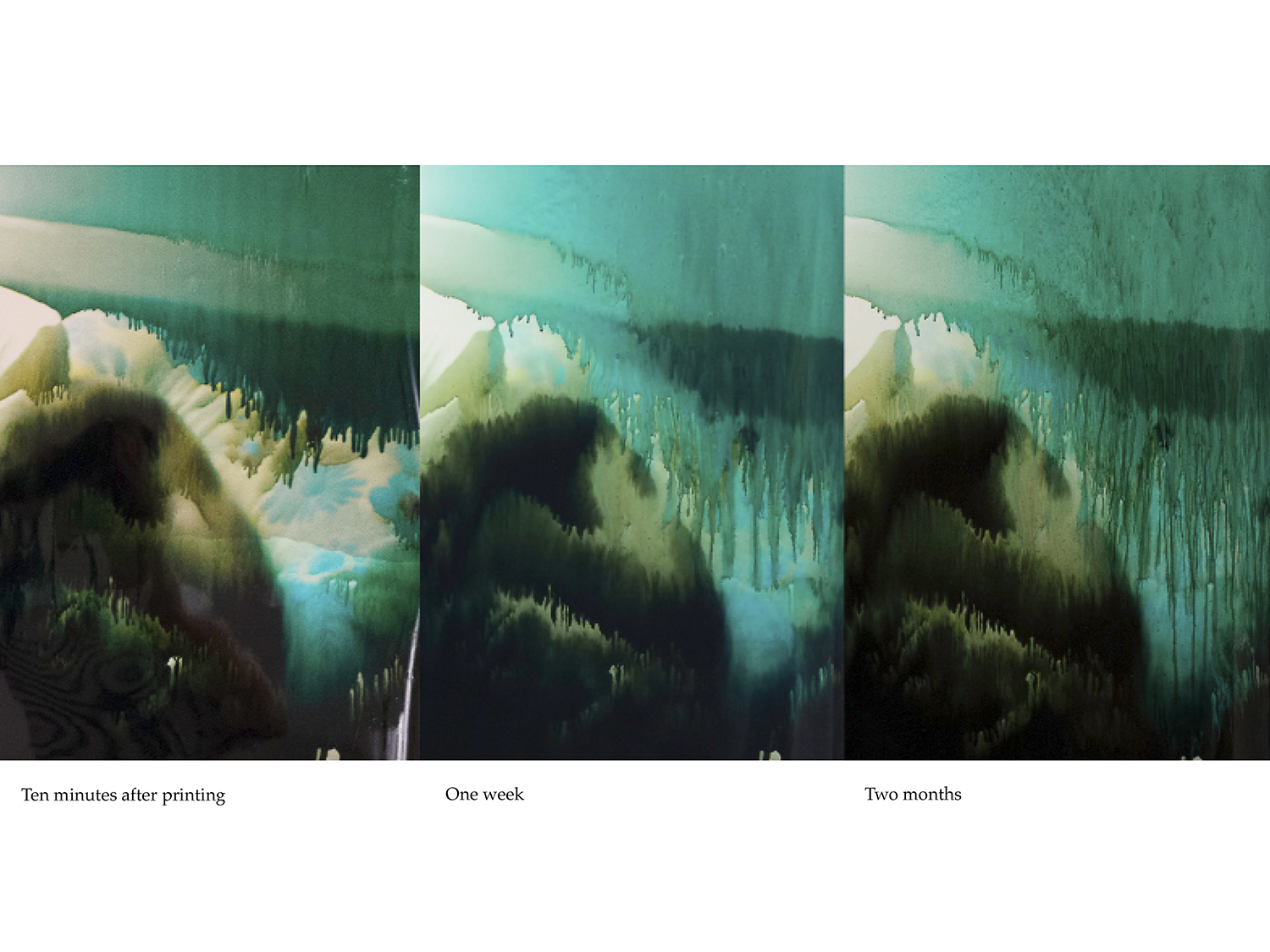

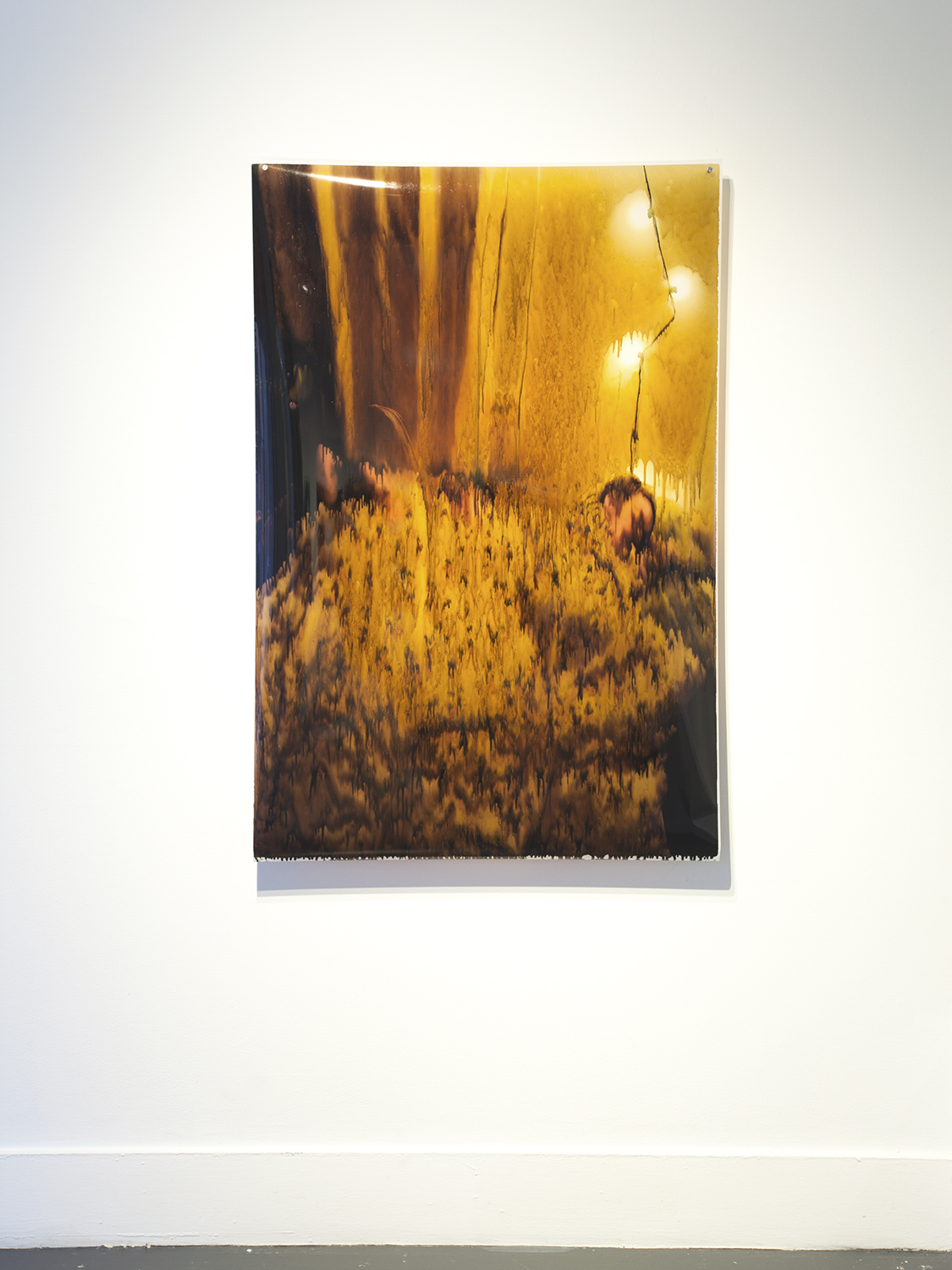

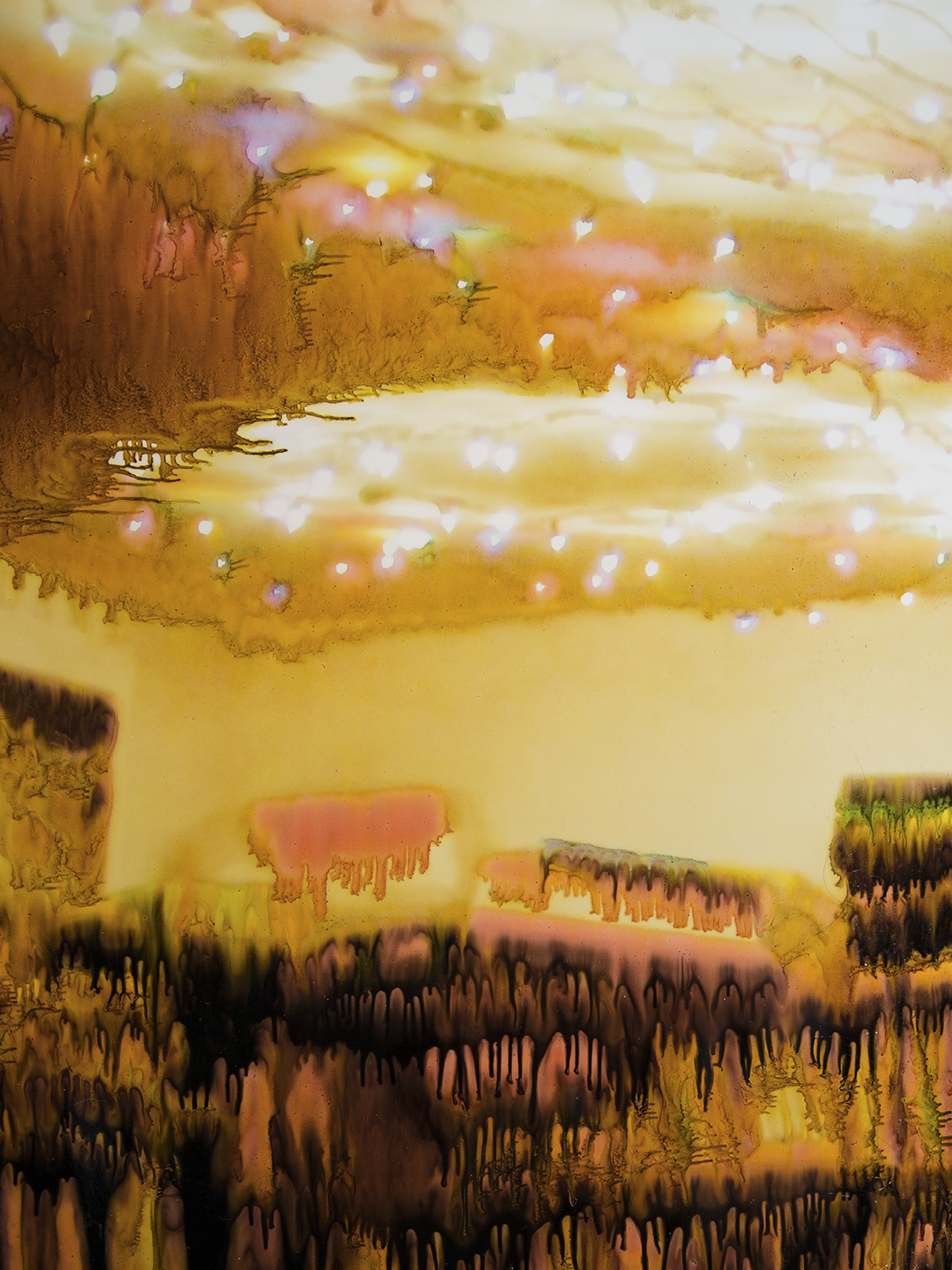

As a multiracial queer individual I have a heightened awareness of how people interpret and categorize bodies. These experiences inform my use of various photographic tools and processes to subvert conventional modes of representation. My recent body of work, Bury Your Gaze, explores “illegibility” as a possible alternative approach to the more commonly valorized goal of “visibility” within a queer context. For this series, I print photographs on a synthetic substrate that repels ink, suspending the images in a liquid, unfixed state. The imaged bodies shift into amorphous shapes that defy assumptions of identity as fixed and challenge the viewer’s ability to categorically label identities. At the same time, the work embodies a sense of chaos caused by foregoing established definitions for the sake of finding new ways to know and understand oneself. Intimacy is entangled with this instability, yet the images maintain the essential tenderness and vibrancy of the exchange between myself and those photographed; often articulated in the saturated, vivid colors. In this series, as well as with all of my work, I aim to evoke visceral reactions that prompt relating not just through intellect but also through one’s body. In doing so, I hope my photographs give material space for intangible, and often invalidated, feelings that relate to queerness

ZJM: How did you come to the physical process for the series?

SK: I’ve been thinking of the condensed version of this, the “origin myth”. The story is couched in grad school. I was working one series of work that I ended up feeling like I mastered in a way after my first year. So I was wondering what to do with it, and I was starting to experiment with different types of materials that I could print on and what I could get away with on these fancy-ass Epson printers. I was looking for something translucent because I was feeling like my original desire to use photography to lend stability and evidence was escaping me. In one such experiment, I bought what I thought was translucent material for inkjet printing (and it turned out it wasn’t) and the ink was running as it came out. I was working with images from my previous series, and the result were these beautiful color fields, but I wondered what the point was in abstracting something that was already abstract? There was nothing at stake in doing that process. I began wondering what type of image would be interesting to abstract or bury when put into this manipulation. At the same time I was reading Judith Halberstam’s book “The Queer Art of Failure” in which the basic premise is, “what’s so bad about failure if what you’re failing is a white-centric hetero-patriarchy?” In one of the chapters she talks about the value of being lost or the opposite of visibility. Maybe there's a benefit to being invisible. And I wanted to inspect what we mean by visibility or legibility. That clicked with this material process.

I have been photographing the people closest to me all of my life, but I have never shown photographs of people in critiques or any public way, because I feel, I intuitively knew and understood that they would be typecast into these (possibly wrong and/or offensive) categories. and that I would be subjecting these people close to me to problematic scrutiny. These are the images that I had to use with this process. I didn’t want to, but I knew that’s what I needed to do. It was forcing me to confront one of my deepest fears, but I also wanted to do it in a way that made sense to me, that wasn’t about explaining queerness or illustrating queerness for an imagined audience that doesn’t know it yet.

ZJM: Is it correct to say that your process is important to your work?

SK: It just dawned on me, do other photographers not think of what they do as process? In some ways there are different lines of work that we call “process heavy”, but is analog photography now considered “process heavy”? On that spectrum it’s interesting because the process that I made this series off of is actually not that different from conventional [photographic] print making.

ZJM: You’re just changing the substrate.

SK: Exactly. It’s almost just highlighting the material reality of a digital print or photography in general. If it was on a normal piece of paper, the ink would be soaked into the paper. But the ink level is same, the speed is the same. It’s really just highlighting the process that exists with digital photography. The ephemerality in and of itself is the point.

ZJM: How long does it take for a print to cure?

SK: Over the first couple of months, there are noticeable shifts in the ink. After about seven to eight months, it is stable as an image, but it remains tacky. It’s a photographer’s worst nightmare.

ZJM: I know that working in such a way would drive some people insane because of the lack of archival stability.

SK: I get it. That’s another misconception. I feel some people think that because I’m doing this that I have some sort of freedom and detachment to these images. No! It sincerely provokes a sense of terror to lose these images that are so important to me! The reason why I gravitated towards the camera in the first place was because it gave me a sense of permanence and evidence as a person who felt in general constantly discredited or not believed or without authority. It was challenging and emotionally taxing for me to do this project, especially to do to images of people I deeply care about.

ZJM: So what is next for you, Sakura?

SK: Lunch! That’s a funny question because in casual conversation when someone asks me this question, I actually double take because I don’t knowif they mean big picture or are you walking my way, but I assume you mean big picture.

Next summer I have a show in Tokyo in a gay bar, Tac's Knot, that the owner has been showing work by gay artists since the 80s or 90s. It’s really an incredible archive that he has.

I feel myself at this juncture or cusp, of course continuing to make work, but really taking the time to flesh out this sense of community that I started in these last two years in grad school. I see myself doing that through teaching, through solidifying these kinds of connections with you and other artists, because it is worth taking conceited effort to make these coalitions among artists, to bring about the kind of future that I want to see.

ZJM: Thanks Sakura, it’s been great talking with you again.

SK: It’s been a real honor! I consider it one of my highest priorities to participate in the culture of art making along side artists who are engaged in the reality of our world—and the complex questions that arise from it. Thank you Zora, for your work as an artist and your work as a member of the Strange Fire Collective.

I would also like to encourage artists, especially q/tpoc, to reach out to me if they find this conversation or my work relevant, we’re all looking for each other! Another world is possible and I’m hella ready.

All images © Sakura Kelley