Q&A: ria brodell

By Jess T. Dugan | July 21, 2016

Ria Brodell is an artist based in Boston whose current body of work addresses issues of gender identity, sexuality, religion, and contemporary culture. Brodell studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and received a BFA from Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle ('02) and an MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts/Tufts University 9'06). Brodell has had solo and group exhibitions throughout the US, is a recipient of an Artadia Award ('14), a Massachusetts Cultural Council Artist Fellowship ('14), and an SMFA Traveling Fellowship ('13). Brodell's work has appeared in ARTNews, the Boston Globe, New American Paintings, Beautiful Decay, and Art New England, among other publications.

Jess T. Dugan: Let’s start at the beginning, in a way. How did you discover drawing and when did it become your primary medium?

Ria Brodell: I don’t exactly remember when I discovered drawing, but I know it was very early. I remember drawing with my grandma and my aunts at their kitchen table. As a kid, especially at school, drawing gave me confidence. I suppose it’s always been part of my creative process.

JTD: Tell me about your project, The Handsome and the Holy. In your statement, you write, “I am interested in the play between queer desire and the construction of gender identity.” Can you elaborate on this idea, particularly as it relates to masculinity?

RB: The Handsome and the Holy was the first time I tried to tackle the subject of my gender identity, sexuality and Catholic upbringing through painting. In that series I was reaching back to my childhood. As a kid, part of me knew that something was “queer” about who I was attracted to, and who I wanted to be (Cary Grant, Ken, the Prince in all the Disney movies), but I didn’t have the language or the knowledge to understand what that meant. The way I wanted to express my gender (in the most masculine ways possible) did not mesh well with having to wear a little plaid skirt to school.

Self-Portrait as Prince Charming, 2009, from The Handsome and the Holy

However, Catholicism was such a big part of my family, and when I was a kid, Catholicism was comforting to me. When creating the pieces for The Handsome and the Holy, I chose to represent those comforting aspects specifically, like my guardian angel, or the story of St. Anthony helping me to find GI Joe’s lost gun, etc. While the self-portraits in the series were a way for me to express my “queer desire,” a way to embody the masculine figures I loved (who always got the girl). They were a way for me to realize that image of ideal masculinity, even if just through paint.

He-Man and St. Michael Find They Have a Lot in Common, 2008, from The Handsome and the Holy

JTD: You reference your religious upbringing as a significant influence on your artistic practice. In what ways has religion informed both your personal identity and your practice as an artist?

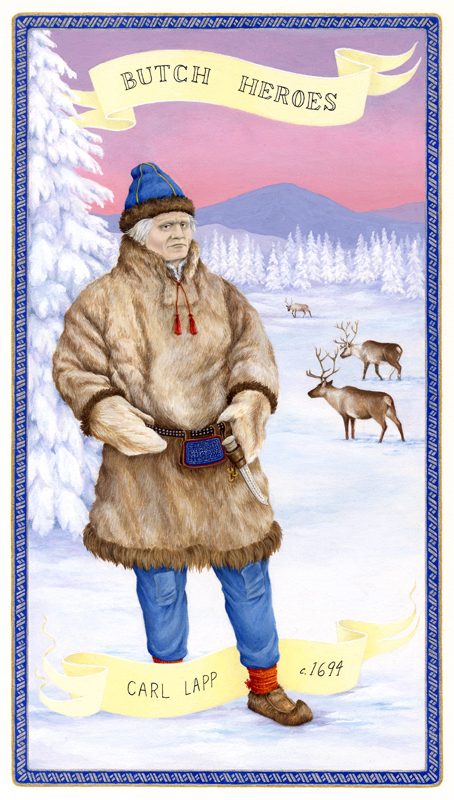

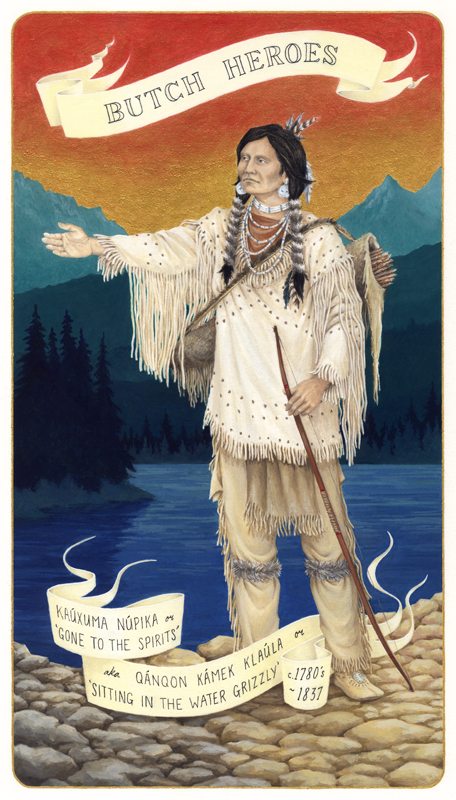

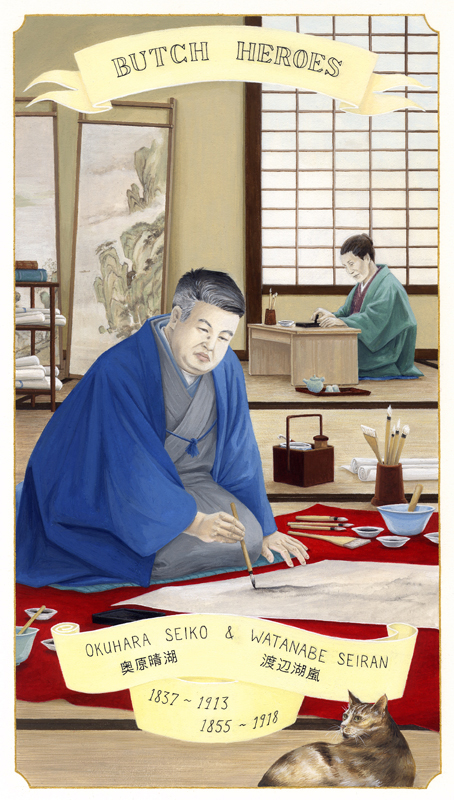

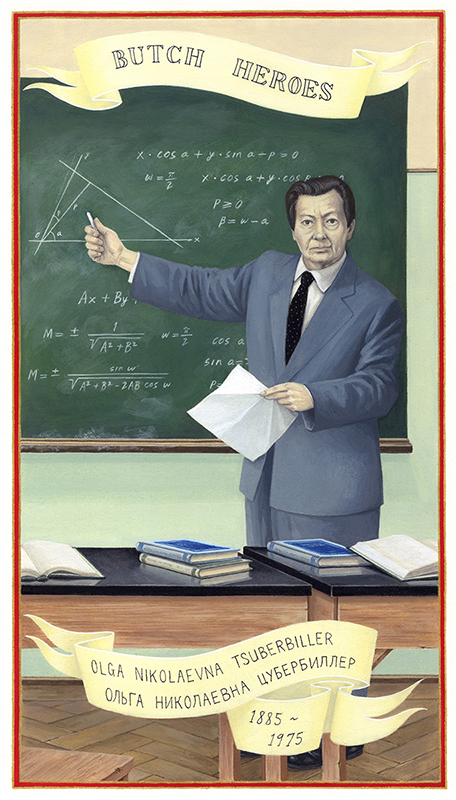

RB: I wouldn’t say my religious upbringing was a significant influence on my artistic practice, as my practice has gone in many different directions, but it is a subject I have chosen to incorporate into two different bodies of work at this point. With The Handsome and the Holy, it was a major part of my childhood struggle with being queer, and with the Butch Heroes, I’m using the Holy Card format because it has personal significance to me, but I’m using it subversively. I feel that I should say that I am not religious any more.

St. Anthony finds G.I. Joe's Gun, 2009, from The Handsome and the Holy

In terms of how my religious upbringing has informed my personal identity, that’s a continuous investigation. I think it permeates many aspects of me: from how I view myself to how I interact with others. It’s hard to point to how exactly, but I know it’s there and I’m still analyzing it. The need to analyze myself might be part of it too. As a queer person, my identity (specifically my gender identity) is something I think about, at some level, on a daily basis. Sometimes I wonder if my religious upbringing is what has prevented me from transitioning. But, at the same time, that need to analyze my personal identity, that struggle with religion, and sometimes with family, has lead me to the research I am doing for Butch Heroes. That project has given me a much larger perspective on gender identity and sexuality than I had before. And, perhaps that has made me feel a little more comfortable.

Man Up!, 2010, from The Handsome and the Holy

JTD: I have always loved that series. So many stories of queerness and gender transgression have been altered or completely erased from history. What was the genesis of this project? How did it begin?

RB: I had done a series of portraits of myself in the future as an old man for The Handsome and the Holy series and the act of making those portraits got me thinking about history. Specifically, how did we survive? How did queer people in the past live their lives? I knew that Catholicism suggested “homosexuals” enter a life of service or at the very least live a life of chastity (I looked that up in the catechism book when I was in high school), so thinking of my options in the past, I made, Self Portrait as a Nun or Monk, circa 1250. After that self-portrait, I decided to dive into history and try to find the stories of real people.

Self-Portrait as a Nun or a Monk, circa 1250, 2010, from The Handsome and the Holy

JTD: A project such as this requires a lot of research. How do you go about finding individuals to portray? What are your primary venues for this kind of research?

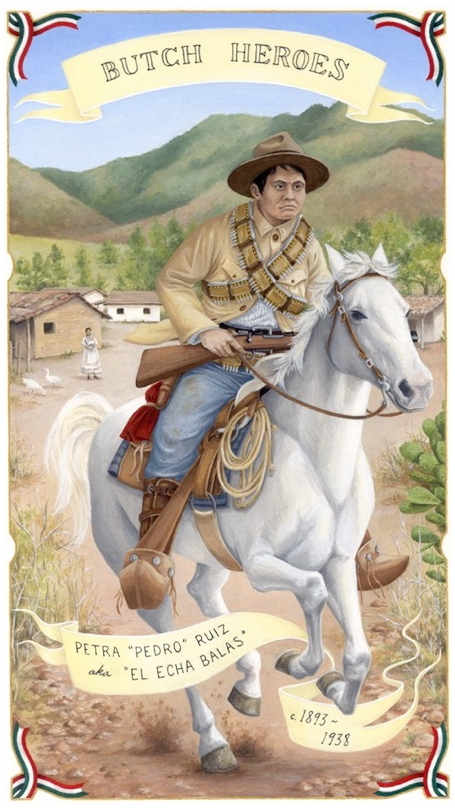

RB: I started by going to the LGBTQ sections of local libraries, Boston Public Library, Tufts, Boston College. Scouring books on our history for names and stories. Finding the names is the hardest part. Once I find a name and a story that excites me I try to get access to the original source, which may be a newspaper article or a personal journal entry, etc. I look for anything that includes the subject’s own voice, or hopefully a description of them. I try to find other sources to verify the information and then I get into all the details, clothing, occupation, setting, etc. That’s the fun part. Figuring out how to represent aspects of their lives visually. At that stage I could be looking at old maps of Stockholm, or buffalo robes at a Natural History Museum, or watching videos on how to plaster a traditional Scottish house. Each painting takes me on a crazy journey.

Jeanne or Jean Bonnet, 1849 - 1876, United States, 2012, from Butch Heroes

JTD: Going back to the idea of religion, why did you choose to draw your butch heroes in the format of traditional Catholic holy cards?

RB: It was a personal and logical stylistic choice for me. I still have a collection of holy cards that belonged to my late aunt. I used to love going through the collection with her, hearing her tell the stories, she had people sending her cards from all over the world. They are beautiful, intimate, and in a way, they are a teaching tool. They’re a way to present role models and to remember those who were important to you. They are still given out at funerals. I thought that was a perfect way to present the lives of people who were long forgotten and abused during their life time, especially because so many of them were accused of “mocking God and His order” or deceiving their fellow Christians.

Charles aka Mary Hamilton, 721 - c. 1746, England, 2010, from Butch Heroes

JTD: What reactions have you received to this work?

RB: It’s been great so far. It’s very exciting. I think the most unexpected part is receiving emails from people I don’t know offering encouragement or wanting to use a particular painting in a lecture or article. I had a library in London contact me because they wanted to include Mr. and Mrs. How in an event on LGBT History. I love that, it’s perfect. And, another thing people say is that they want a book, so that’s in the works too.

JTD: Speaking of a book- what are your plans for the project? Do you have a sense of when the project will be finished, or do you envision it as something you will continue over a longer-term period?

RB: So, yes a book is in process. It will include all of the portraits and the stories that I’ve completed to date, one or two essays by guest writers, and all of my research sources. I’m currently in the research stages for the twenty-fifth portrait. I will be showing them for the first time at Gallery Kayafas in Boston in March/April 2017. At this point, I plan on keeping the project going. I would love to find people to paint from areas of the world where I have found the research to be difficult, particularly Africa and the Middle East.

JTD: Representation is so important. Especially now, in light of the gains made by the LGBTQ community and also in light of the negative backlash as a result of these gains, how do you view your role as an artist as you capture our community’s history and create representations for others to see themselves reflected? Do you view your telling of LGBTQ history as activism?

RB: I think you said it well. As an artist I do want to, “capture our community’s history and create representations for others to see themselves reflected.” I have always believed that our history is important and shouldn’t be forgotten. We can learn so much from history, and there are so many parallels with what is happening today. In terms of whether I view my work as activism, I admit it’s nice to think of it that way. Maybe it’s more gentle activism.

JTD: What’s next for you as an artist?

RB: I don’t know what’s next really, but I always have a “side project” going on. Currently that’s my Daily Drawing Project. I started it to keep up my drawing practice and as a way to focus mentally. Another strong interest of mine is animal rights and conservation, so I have taken to drawing a different animal every day. I’m calling the project: Kingdom Animalia, and I’ve made over 200 drawings.

American Robin, January 4, 2016, from Kingdom Animalia

All images © Ria Brodell