Q&A: nabil gonzalez

By Jess T. Dugan | November 17, 2016

Nabil Gonzalez was born and raised in the border city of El Paso, TX. She received a double BFA from the University of Texas at El Paso, where she studied Graphic Design and Printmaking. In 2016, she obtained her MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design where she continued her studies in Printmaking. Nabil has exhibited works nationally and internationally, including galleries and museums in the U.S., Mexico, China and Colombia. She is currently living and working from her home town of El Paso, where she has continued her research on the disappeared women of Ciudad Juarez, a city located across the border in Mexico. In her work, Nabil explores the erasure and reestablishing of identity through repetition and layering of images, marks, and materials. Often, her work contains haunting messages that unfold slowly through the varied and multilayered surfaces she builds up over time in her works. Through her work Nabil tries to bring awareness to a society that has become numb.

Jess T. Dugan: Let’s start at the beginning. How did you discover your passion for making art and what led you to pursue a career as an artist?

Nabil Gonzalez: Well, as far back as I can remember I have always been interested in art. As a child I would spend most of my time drawing, coloring or making some sort of crafty project rather than going outside to play. But as I got older I started to feel a real connection with art making, and when I was 14 years old I took my first art class. Somehow I felt that art gave me a powerful voice and it allowed me to express and share my feelings, ideas and opinions with the world. Soon after taking my first art course I discovered art can be a very powerful and universal language and how an image can carry so much information and reveal so much. I’m a very quiet person, so art gives me that powerful loud voice I need to capture peoples’ attention and communicate my ideas and opinions with the world through a creative outlet.

JTD: Much of your work focuses on the disappeared women of Juarez. Can you tell us about this epidemic and what drew you to make work about it?

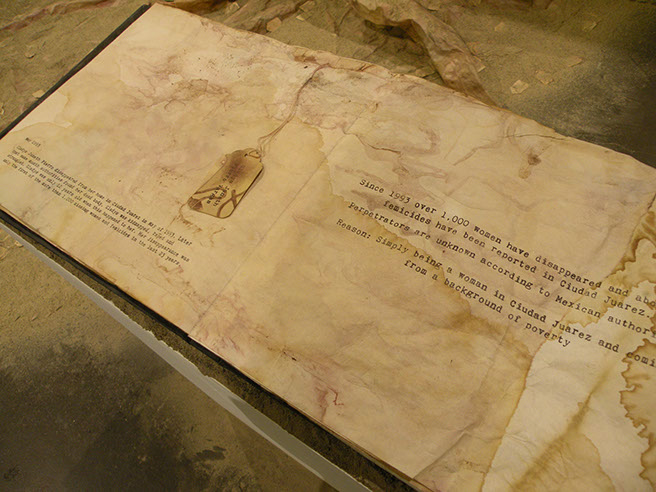

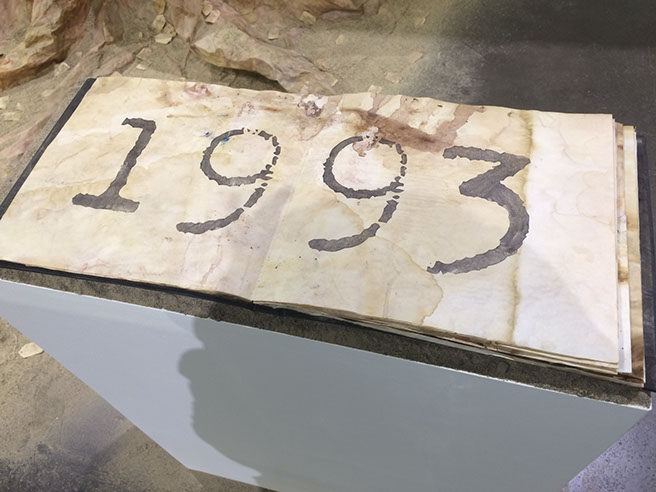

NG: Yes, so the disappeared women of Juarez or Las Muertas de Juarez is very serious epidemic that first struck the border city during 1994, also being the year when the North American Free Trade Agreement was agreed to by both American and Mexican presidents. NAFTA “meant” new beginnings for the border city; it meant Ciudad Juarez would become an industrialized city that would bring new opportunities and well-paying jobs for the Mexican people at the many maquiladoras (factories) that migrated from the US to Mexico with the sole interest of finding cheaper labor.

Maquiladoras attracted large numbers of young women in search of“well payed” jobs so they could pursue their dreams of obtaining a higher education and helping their families con el gasto (provide). A lot of these women had no choice but to take on the night shifts due to high demand, which didn't sound that bad being that the factories provided their workers with free private transportation from their neighborhoods to the factories and back home.

So it’s no news to the world how the Mexican system is very corrupt, so soon a lot of the factories became corrupt allowing drug cartels to manipulate them and distribute and sell drugs within the maquiladoras. This lead to an even worse problem: young women started disappearing “mysteriously" from their course of going home to work or from work back home. The women were being abducted from the factories by men who worked for the drug cartels. Many of the disappeared women were forced to participate in orgy parties organized by the cartels, where the women were physically abused and brutally raped and then murdered. Some of the most powerful families (by powerful I mean they own very important corporations in the city and control more than half of the city and the government) from Ciudad Juarez (I will not include any names) are known to have participated in these crimes as abusers and murderers. The lifeless bodies of the women are then simply discarded and thrown in Lomas de Poleo located just on the outskirts of the city. That’s not always the case: sometimes the bodies are completely disappeared.

Let’s also not forget the other women that disappeared as the years went by. They not only were disappearing from the factories at night but also from the downtown area of the city and even in broad daylight with numbers of witnesses around. It’s been about 23 years and so many women have disappeared, there have been countless protests by the victims’ families against the local and national government for their lack of action against such an outrageous social and political issue.

Nuestras Hijas

JTD: You grew up in El Paso, TX, just across the border from Ciudad Juarez, and regularly heard about the disappearance of women and girls throughout your own childhood. What role does your personal biography play in your work?

NG: I think that by living in the border growing up I was well aware of what was going on and in a way exposed to this because I was a young woman growing up in the area often visiting Ciudad Juarez on weekends with my family. As I got older (by older I mean 17), I started visiting Juarez at night with my friends to go out to night clubs and take advantage of the fact that we would not get carded at night clubs because we were young women from el otro lado (we were American). It wasn't until one of the many nights visiting Juarez that I had an experience that put me in danger that I realized I could have been one of “them.” I think this personal experience was what made me REALLY aware of the danger it meant to be a woman living in Ciudad Juarez. This experience was what lead me to focus my work on this issue, it made me feel the need to be a voice for the disappeared victims.

I think that by having gone through that experience and by growing up in the border and hearing about this problem practically my whole life, it affected who I am as a person and specially who I am as a woman. I believe that it was that personal experience that lead me to want to make the world aware of the reality these women and families live every single day of their lives. It made me feel the need to be a voice for the disappeared victims and reestablish their identity in society. So what better way to achieve that than by reaching out to the one thing that gives me that powerful voice I need to get peoples’ attention, ART? The only language that allows me to go beyond borders and raise questions among present day societies and encourage important conversations amongst ourselves.

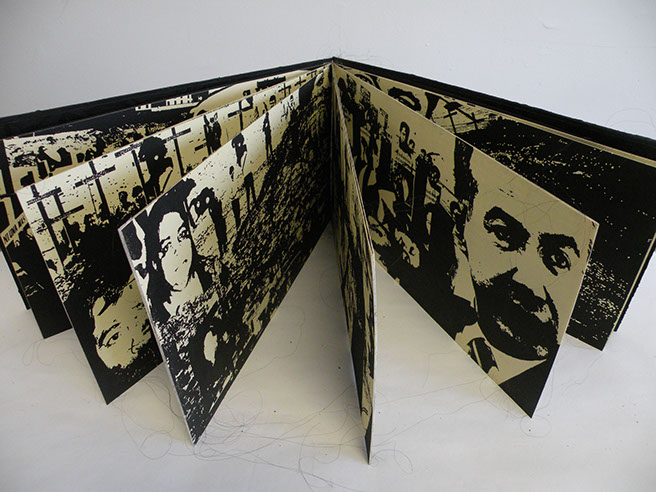

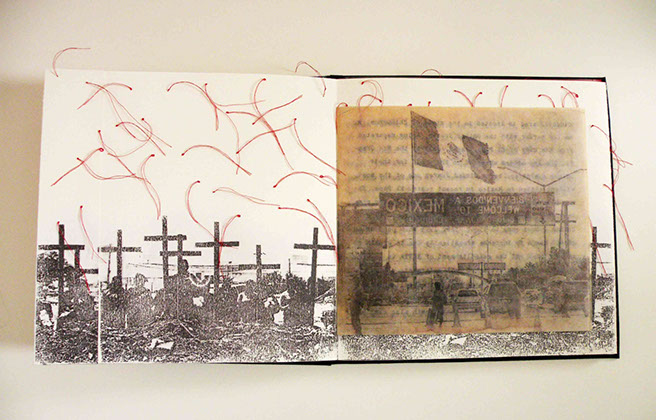

Desaparecidas

JTD: In your artist statement, you say that you “want to be a voice for the countless disappeared victims of social and political crimes.” How does this goal manifest in your work? As an artist who is socially and politically engaged, what kind of responsibility do you feel when making work?

NG: Yes, I want to be a voice for the disappeared victims. I think it’s important that society doesn't forget who these victims are and most importantly that they just don't become a case reference number. Throughout the past four years I have been able to find around 400 names of women that have disappeared and I feel the world should know their names. If you look at some of my works like 1994, Desaparecidas, Memento Mori and Femicide you will be able to find the names of the disappeared women. Including their names in my work has become very important to me because I feel that I acknowledge and remember every victim’s existence and memory with every action I take in producing that specific piece of art that contains a name. It also becomes some kind of ritual because every time I make a piece with a victim’s name I repeat that name and it stays in my mind.

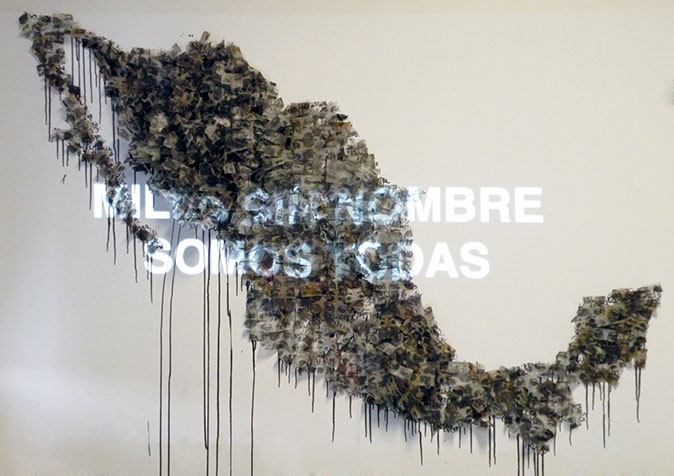

23 Años de Silencio

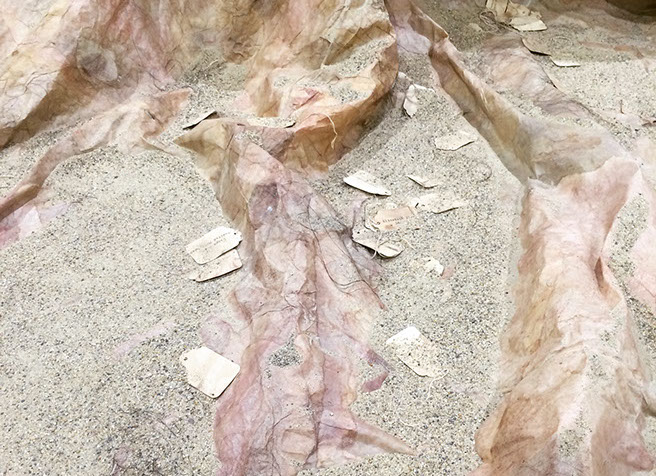

Repetition is one of the strongest elements present in a lot of my work. For example, if you look at works like Rastros, Somos Todas, Nuestras Hijas and 23 Años de Silencio you’ll notice that they all have one thing in common and that is the element of repetition, whether it’s an image, a mark, or an action. I feel that by repeating something so many times it starts to have a real meaning, people will start to notice and wonder what the meaning is behind the work. I also see it as a way to visually represent the severity of the problem and the enormous number of disappeared women.

It’s a big responsibility to make this kind of political work that involves lost lives because I’m always concerned about what the victim’s families would think of my work if they ever saw it. I think that respect is the most important thing here. I have to really think about what I’m going to do next and what it is that I want to say with my work because I don't want to offend anyone. My goal is to educate societies of the reality these women and their families went through and create important dialogs in present day societies.

Rastros

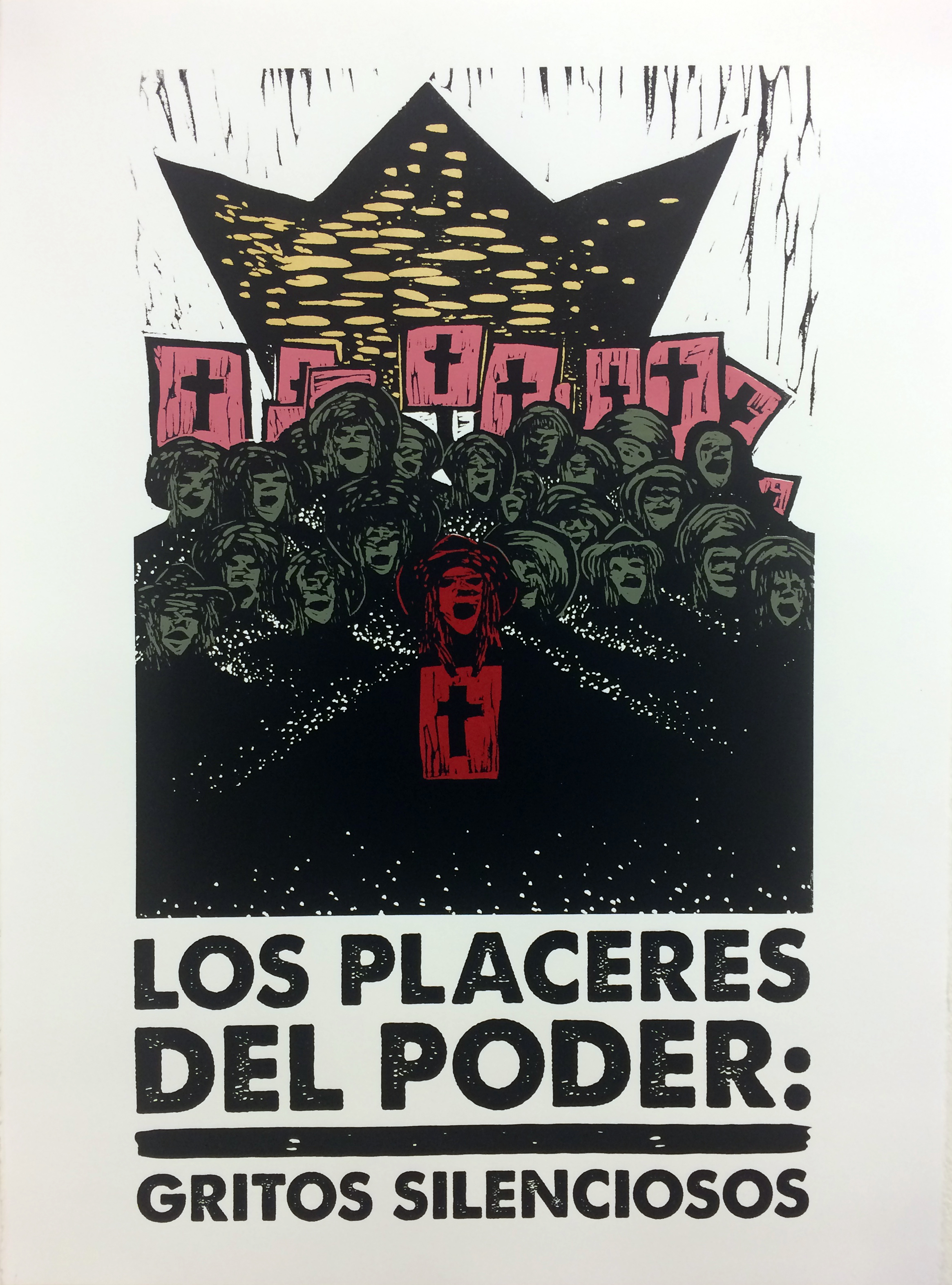

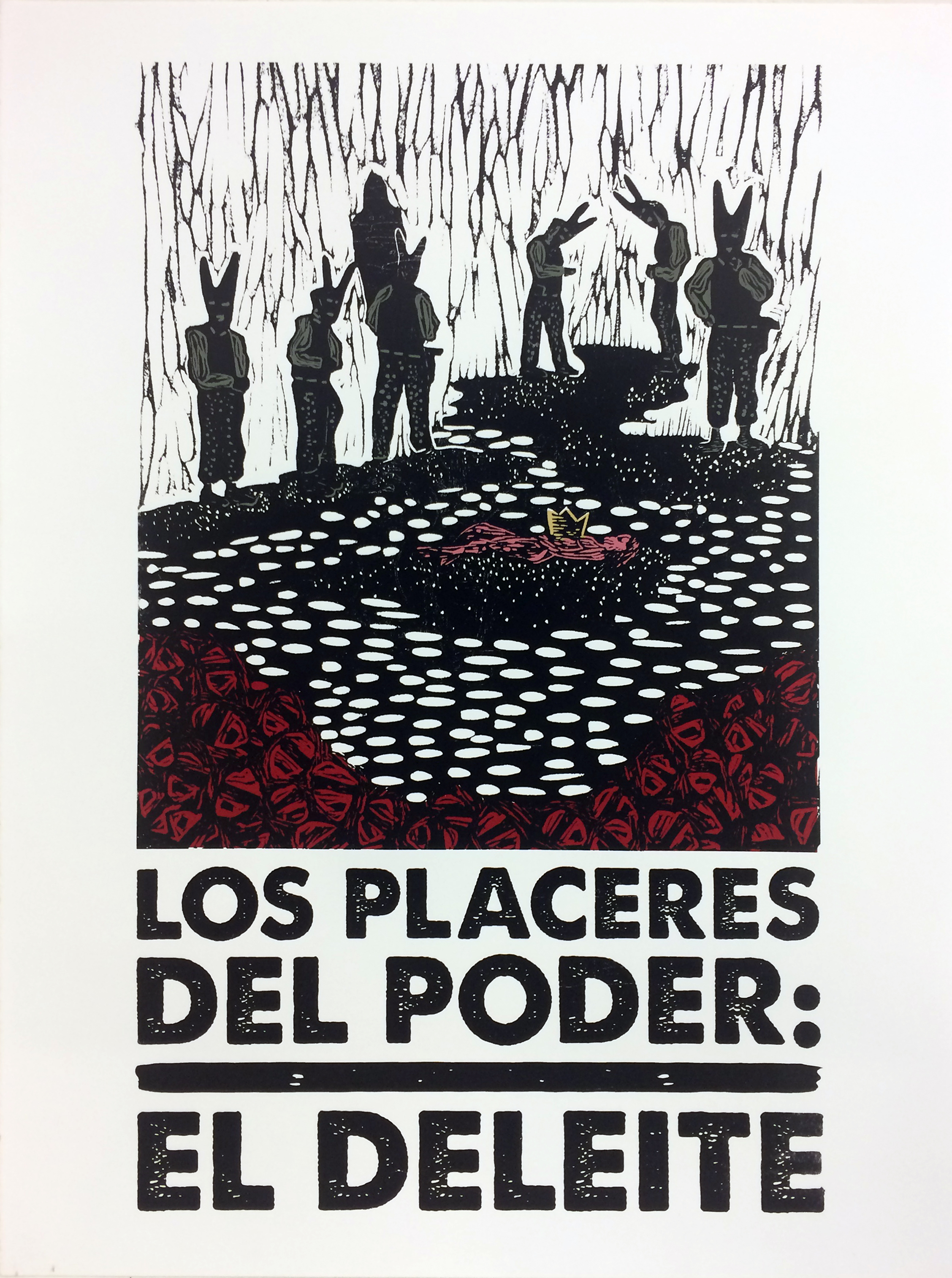

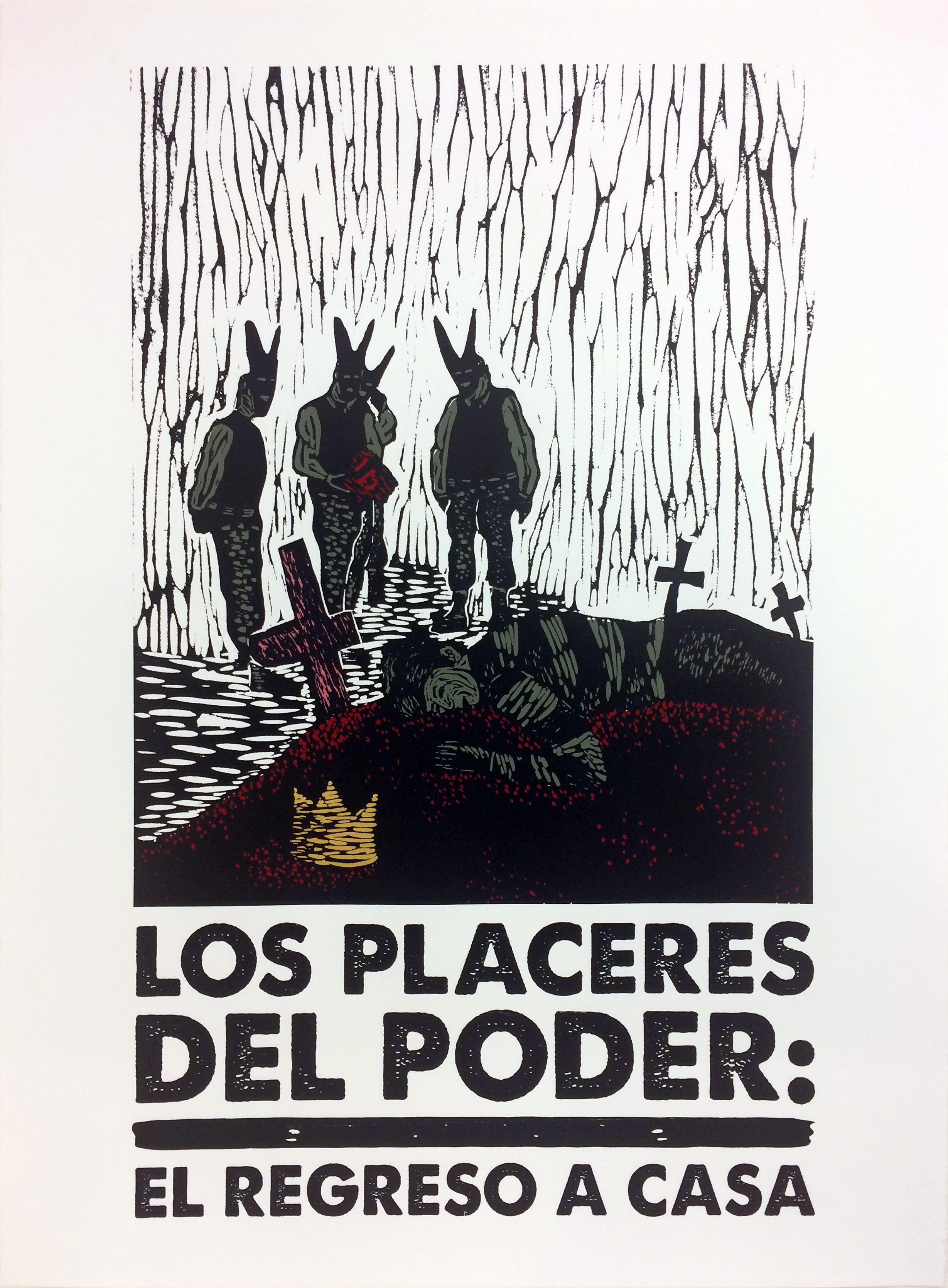

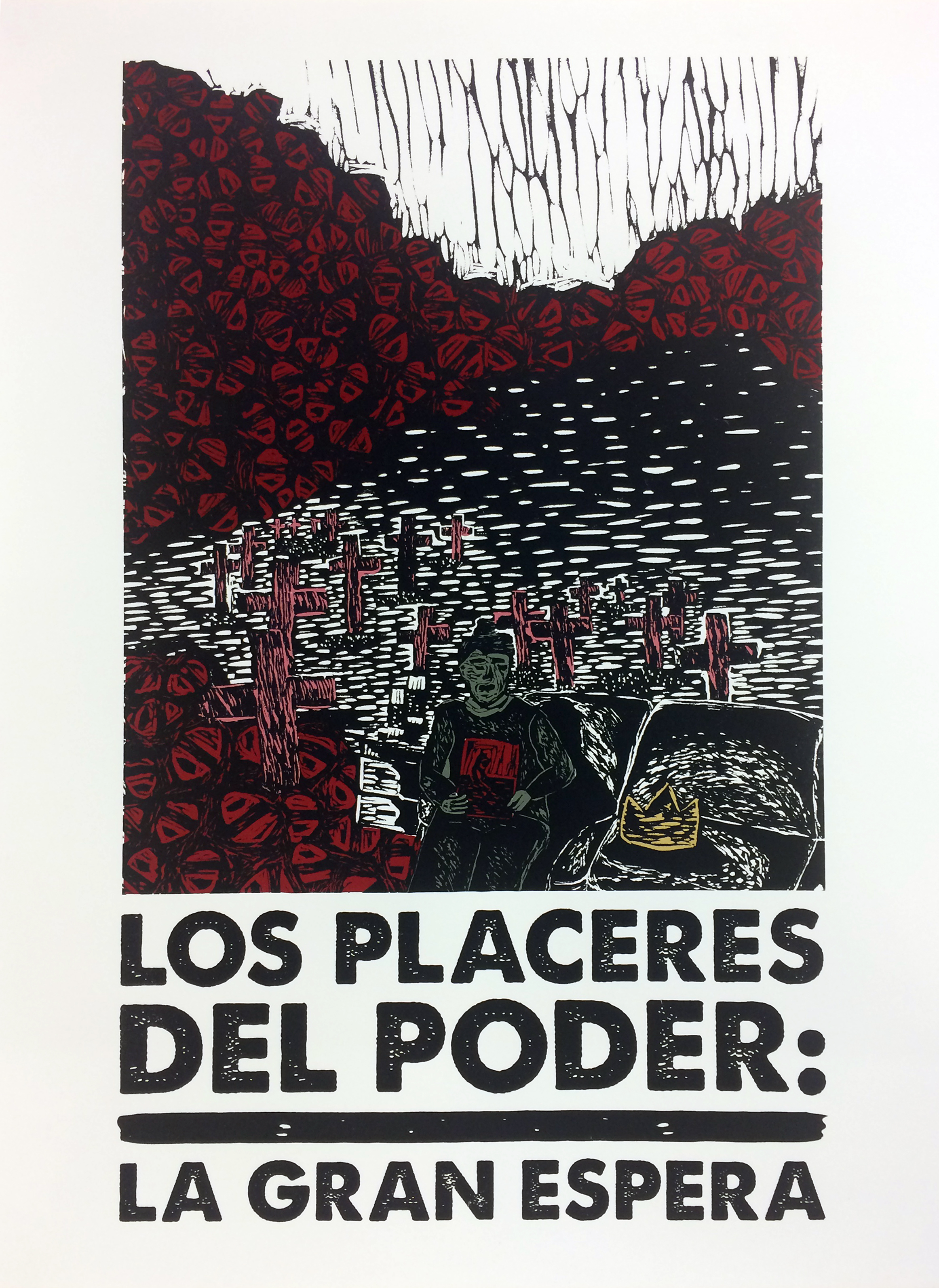

JTD: When we met recently, I was particularly struck by your poster series “Los Placeres del Poder.” Tell me about this series and how it came to be.

NG: Los Placeres del Poder started as a series of drawings and an investigation of my understanding of the problem. It was a kind of exercise for me to get back into drawing and trying to illustrate the way I saw and understood the problem in my head. It was a real challenge for me. It forced me to step out of my comfort zone because I’ve never seen myself as a good illustrator. Most of my work comes from photographs and collages that have been some how manipulated in Photoshop. I think this series of drawings were such a success that they became the illustrations for my thesis writing. I feel they really tell a story from beginning to end.

After completing the series I was really drawn to the drawings and felt they could be pushed a step further so a few months back I started doing some research on traditional Mexican protest posters made by activist students in the 70s. I found the quality of the posters so interesting, especially the violent marks that are so particular to woodcuts or linoleum cuts. I just wanted to try it. This series of Los Placeres del Poder is still very new so I’m still trying to understand it more, but I feel they still have that narrative story that the original drawings have even though the posters are much simplified.

In a way I think the posters are more violent because of the nature of cutting into a matrix to create an image. When I think of my work I don't just think about the finished product but of the entire process from the initial idea to the execution process and the making of the work, of how violent some processes can be.

Los Placeres Del Poder: La Bestia

JTD: Your work situates itself within the museum or gallery world as well as within a more overtly political environment. Within your project “Los Placeres del Poder,” you have a limited edition set of prints intended to go to museum exhibitions and collections and you also plan to create a mass produced edition that can be wheat-pasted throughout El Paso. How do you view these disparate formats and audiences, and in what way do you balance these two separate outlets?

NG: I think that yes they are two very different outlets. The museum feels like a more controlled environment and the “real world” feels like a more freely open outlet. I definitely think that the conversations would be totally different. The museum setting will always provide the viewer with more information regarding the work and to a certain extent the conversations would be more educated conversations versus the dialogue that a wheat pasted poster on some public space would have. The museum setting is a more controlled environment and it attracts a specific group of people (people that are interested in the arts). Because this is the case, I feel like it limits my ability to reach larger, more diverse audiences. I feel that by pasting the posters around the city, especially close to the border, they will reach more people, perhaps even people that would never step foot in a museum. I feel that street art has a louder voice because the art seeks the viewers.

JTD: Depicting violence can be particularly challenging. Graphic imagery sometimes functions as a call to action, while other times it risks making us numb to the atrocities of a particular situation. What concerns do you have about depicting violence, particularly sexual violence, and how do you negotiate this challenge in your work?

NG: As people, we tend to shut down when we experience things that are not so pleasant, especially when it comes to violent acts. Yes, we might feel sympathy towards the victims but we tend to stay away from those kinds of things because we don't want to be thinking of such horrific acts the rest of our day. So when I depict such acts in my work I have to be very careful how I do it because I don’t want to push people away from my work. I have to find different ways of portraying those acts of violence. I don't like being so literal. I like keeping that element of suspense, so I use beauty to bewilder my viewers and capture their attention leading them to study the work more deeply. A good example of this would be one of my most recent works, “Femicide.” As you study the work you can start bridging those connections between imagery, materials, textures and sometimes even scents. When this starts to happen I think the viewer’s reality has been changed because now they’ve become aware of the violence and they’ve somehow become aware of it without really knowing. Now when the viewer encounters those textures or scents in the future, maybe they will be able to make a connection to my work and the violence being portrayed.

JTD: Your practice as a whole incorporates printmaking, photography, sculpture, and installation. What role does each of these media play and when do you decide to use one or the other?

NG: It’s all a process. Most of my work starts as a photograph that I then edit in photoshop or by hand. I abstract the images by layering the same image several times, by removing information or by collaging different images together. Once I’m happy with an image and I feel it’s interesting enough, I then transform it into a printing matrix, which then adds another layer of transformation. I feel that my processes is a metaphor to my topic because it starts as a photograph that tells a “truth” but then it gets transformed so many times that it starts to loose information and its initial “truth,” just like the identities of the women. They start as an individual with an identity but they get so corrupted by the government that society forgets about them and they just become a case reference number.

Printmaking is intuitive in my work. It feels like it’s my default mode: everything starts as a print but as I go on with the project I start making other decisions and that’s what leads me to transform a simple print into an installation. It all depends on what I'm visually trying to represent. On the other hand, my decision to make sculptural work is very recent but I feel that my sculptural work still has a lot of printmaking references. The repetition is still there and, to a certain point, the matrix is still present. For the most part everything I make starts as a print and then I let it morph as I go on. I really don't have a specific set plan for each piece. I make decisions as I go and see where things take me. Maybe it ends up as a simple print or somewhere along the process it turns into something completely different.

JTD: What is on the horizon for you as an artist?

NG: I have made it my mission to be a voice for the countless unheard victims and to try to acknowledge their existence with every mark and action I make in my work. I will definitely keep making political work that sparks a curiosity and creates important dialogues in today’s society. Maybe it will serve as a call for action, but I know that what I do with my work is very heavily charged that it’s not just simply art. I will definitely keep making political work, especially with the recent elections. I have so much to say and I will keep doing it as long as art gives me the powerful loud voice I need. Let’s not forget the rich history printmaking has of being an outlet for protesting against a system. Print is not dead!

All images © Nabil Gonzalez