Q&A: Logan Bellew

By Rafael Soldi | January 11, 2018

Logan Bellew is a photographer and independent arts project manager based in Brooklyn, New York and Nicosia, Cyprus.

He has worked for and contributed to projects and publications with the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Scottsdale Public Art, The Tamarind Institute, The Phoenix Art Museum, The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, The Santa Barbara Museum of Art, the Getty Foundation, The Princeton University Art Museum, Alexander Gray Associates, and Galeria Fortes D'Aloia & Gabriel among others.

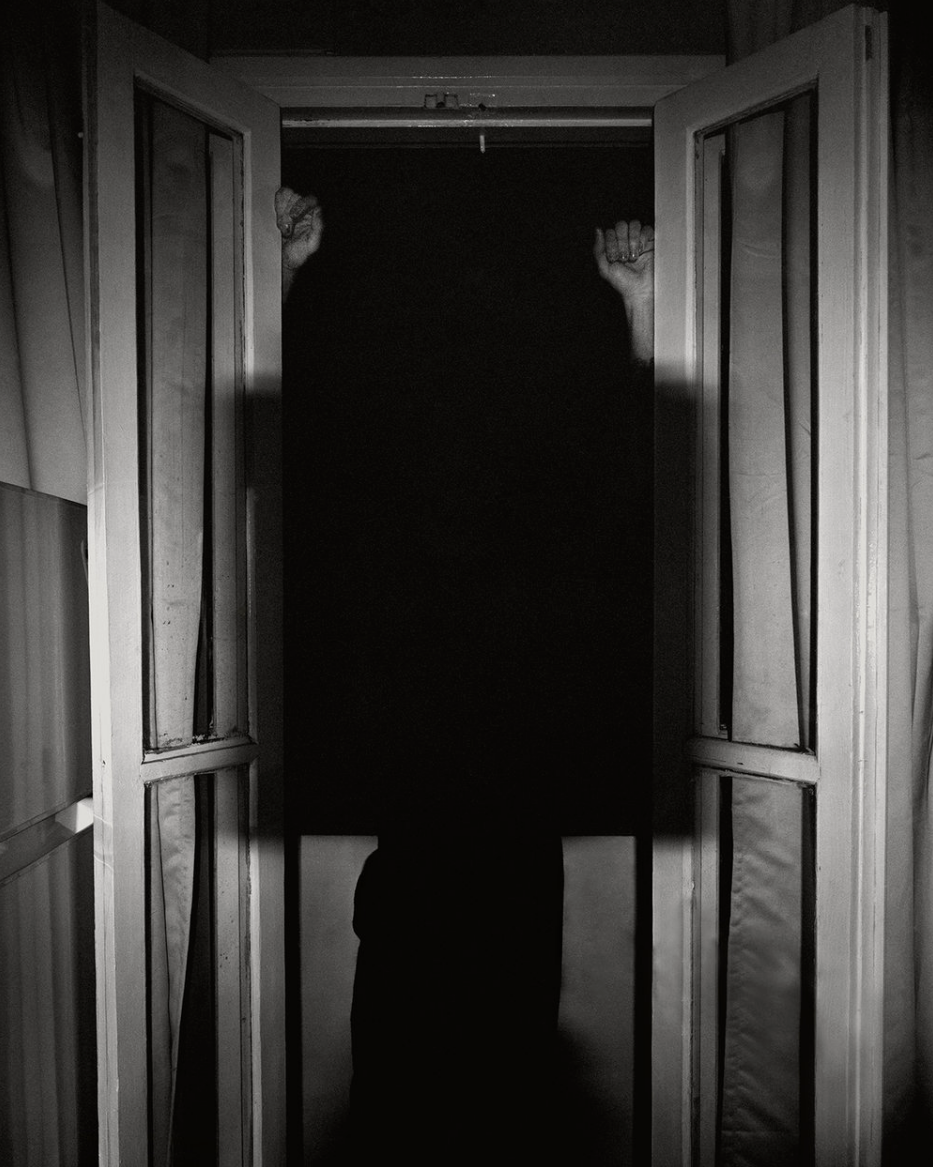

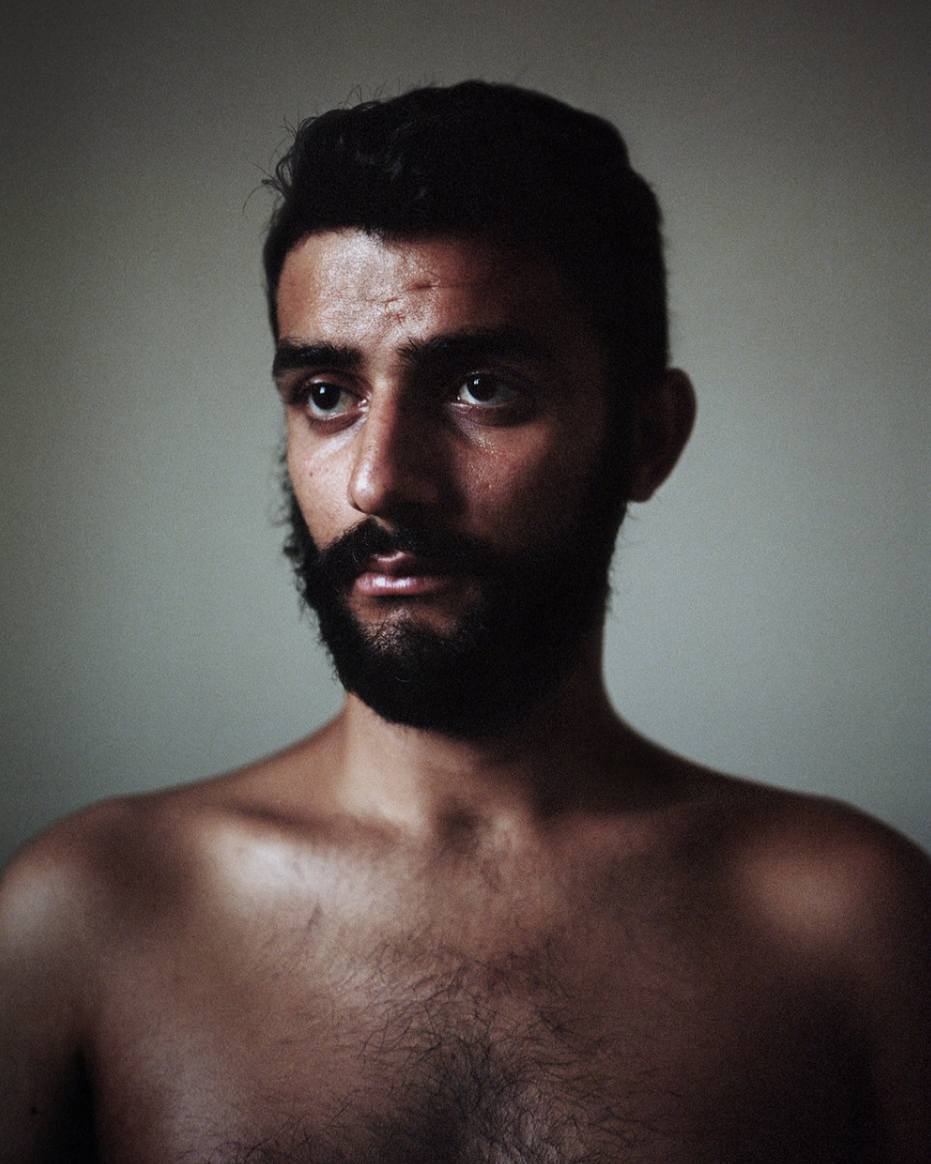

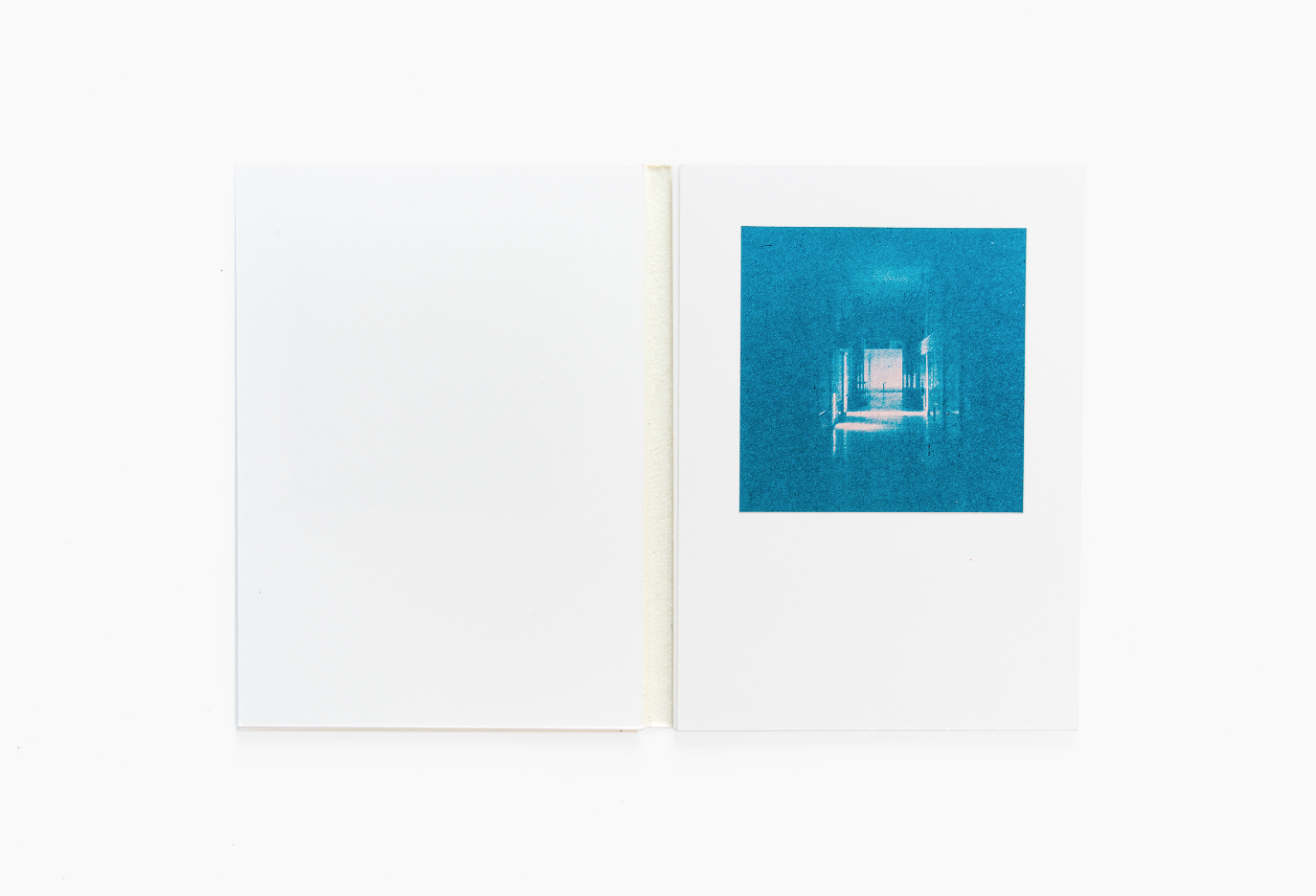

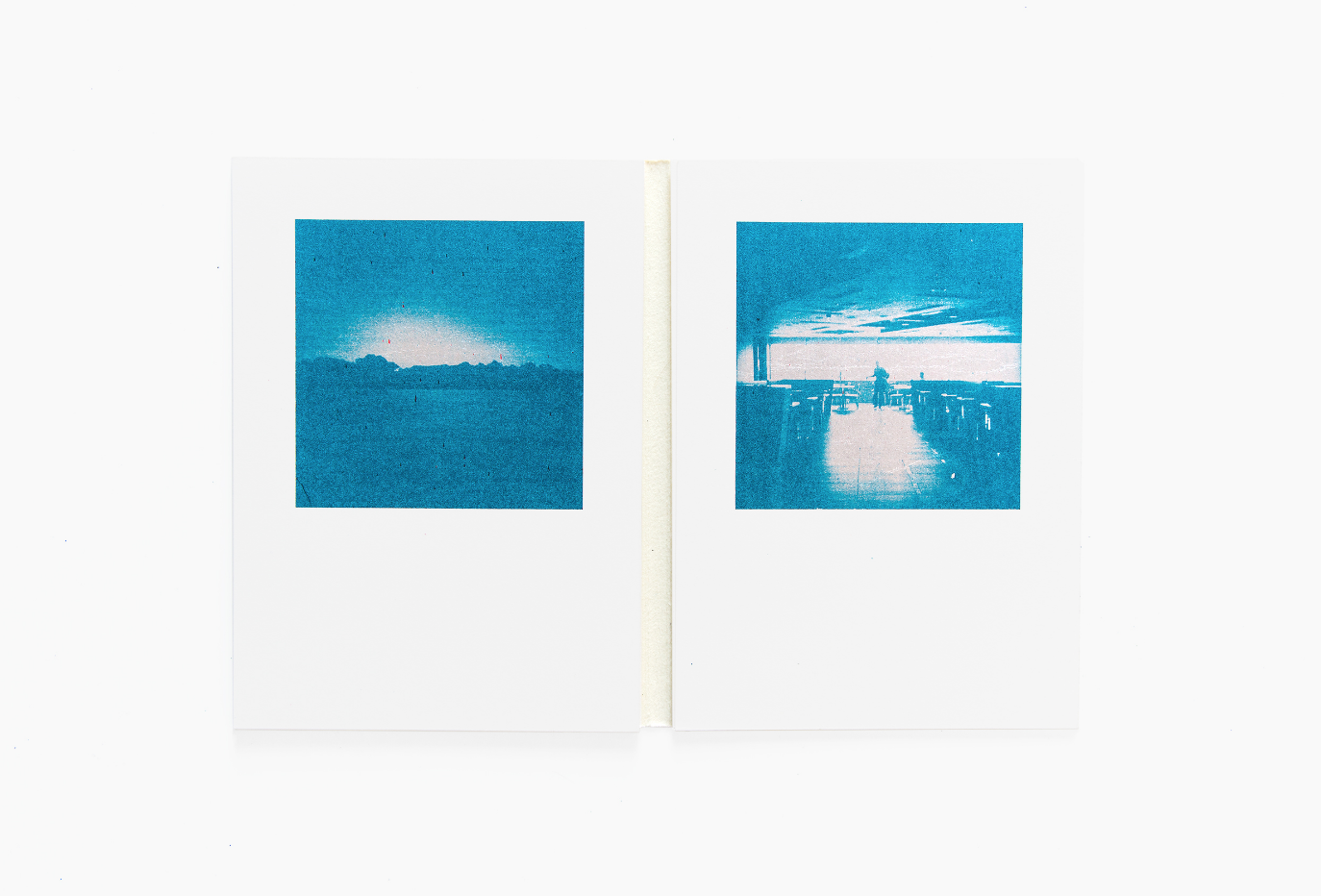

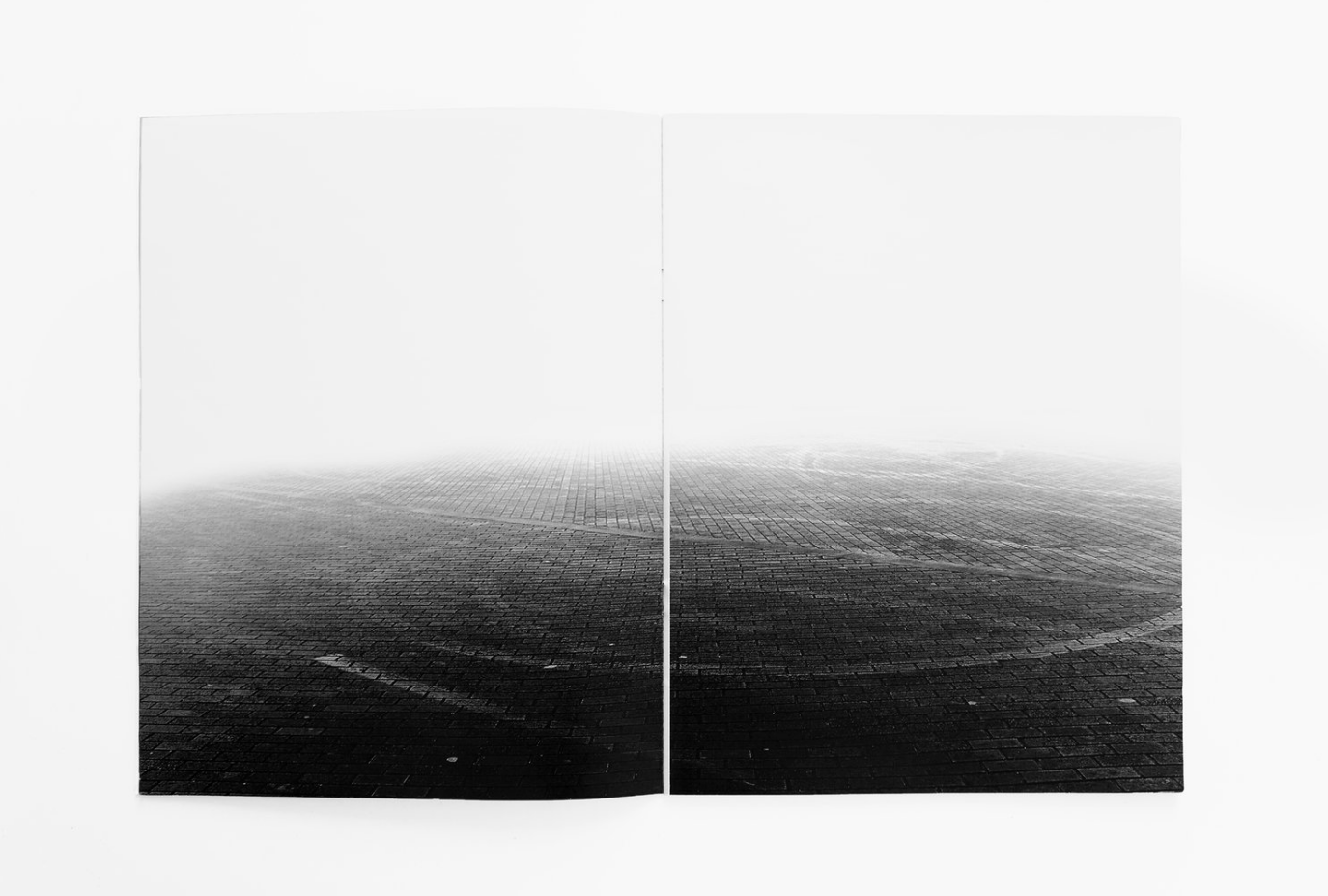

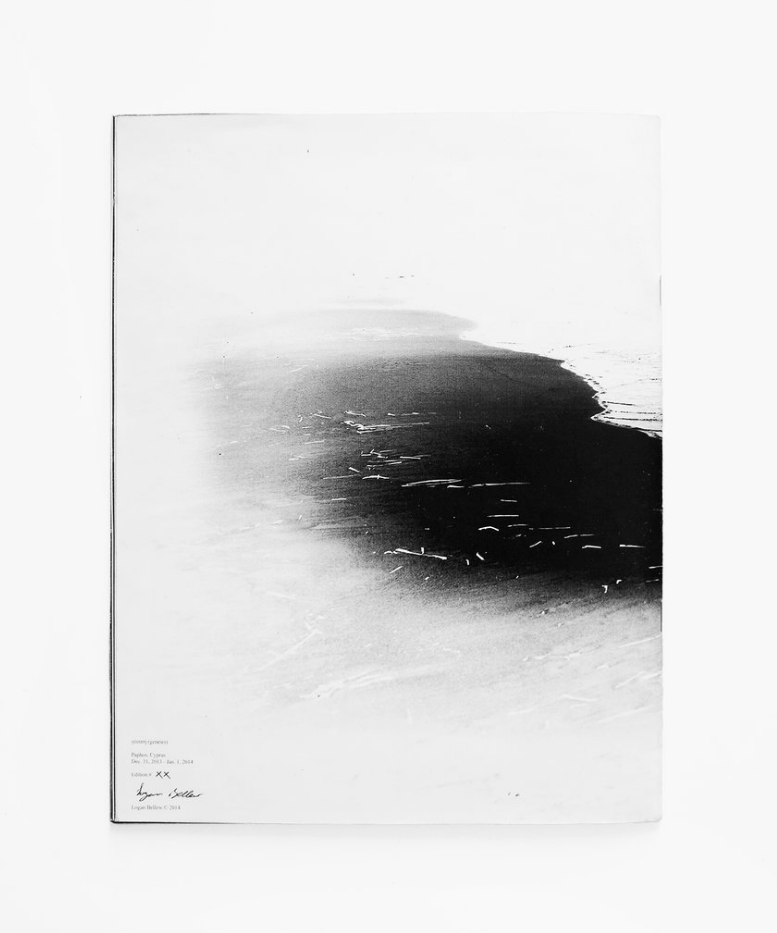

From Eros - Transformation

Rafael Soldi: You've rooted much of your practice in Cyprus, how did you come to spend time and form an identity there?

Logan Bellew: My relationship with Cyprus developed in one of those ways you can’t really plan, but is the product of unfolding and overlapping events. I first went to Cyprus in the summer of 2011 to work as a photographer on the archaeological excavations in Polis Chrysochous. I was invited for a second summer in 2012 and became interested in meeting and photographing other gay men. I’ve always been interested in what it is like to live beyond my own backyard, so the camera in this instance was a means of accessing and understanding how a gay person like myself lives in this place. My relationship to the island, at least photographically, changed after I was diagnosed with HIV. It was determined I had most likely contracted it while I was in Cyprus, so I decided to go back again with my camera. Initially I was driven because I wanted to make a record of this place, to somehow gain closure, but my relationship changed visit by visit. Now I work with the AIDS Solidarity Movement of Cyprus which connects me on a personal level to so many people, and I’ve grown more comfortable in my own skin. I’ve also made a lot of friends in Cyprus, and they won’t let me be away for too long.

From Eros - Transformation

RS: Your body of work Eros - Transformation is an ongoing collaboration with a former-lover-turned-friend. Overtime I can imagine he is as much a subject as a reflection of you, your relationship with one another, and with that particular place. How does he function as a muse?

LB: I met Pete in the summer of 2015. When I first returned to Cyprus in 2013 I hid my HIV status. That hiding and the secret I was keeping began to cause a divide. In our last discussion you mentioned John Szarkowski’s exhibition Mirrors and Windows, and asked me if I thought I was a mirror or a window. What struck me most about this conversation was the shared sentiment that we as photographers often don’t function as either or. When I returned to Cyprus in 2013 the camera in this sense functioned as a mirror, a reflective barrier I had erected around myself, but through which a tiny aperture, a window, allowed me to look. The camera allowed me to mediate and keep my distance, but also to slowly reveal this piece of myself. As my relationship with Pete developed our photographic encounters became charged, and the act of looking became a way for me to participate in the erotic consumption of another. But still there was fear involved. The fear for me at the time was not only a mourning for the carnal sensation of another, but also and more to the point, that the capacity for love and to be loved had escaped me entirely.

The Greek poet Sappho characterizes Eros in one of her aptly named Fragments as “sweet-bitter,” while others have described it as missiles tempered in honey and cold ice melting in warm hands. Anne Carson even describes Eros as “what hits the raw film of the lover’s mind. Paradox is what takes shape on the sensitized plate of the poem, a negative image from which positive pictures can be created.” I find Carson’s metaphor of a film negative embodying the paradox of Eros to be only too sweet. It begs the question of what happens when you photograph those you desire, a muse, and what happens still when you put those photographs on display for others to see? I look at Pete’s eyes, his mirrors, and the flashes of light piercing through his dark irises cause me to doubt myself and speculate. Is he mirroring my gaze as I look at him with ringing and pain in my ears after he’s turned the volume on the car radio all the way up? Is that the look he gives me after I’ve made him stand still in an unairconditioned apartment with his full army uniform on, or in the freezing mountains shivering? After I ask him to stand in front of the car that symbolizes one of the things in his life that brings him pain and reminds him of his flaws? Roland Barthes in A Lover’s Discourse says “In the amorous realm, the most painful wounds are inflicted by what one sees rather than by what one knows.”

This body of work isn’t complete, and I’m not sure it ever will be. These photographs are about two lives coming together and in another way moving apart. I mean this in both the sense that the subject of the photographs are indeed two people, Me and Pete, but also in that my own life feels divided and mediated by distance. I have a life here in the United States, and I have a life in Cyprus that languishes in my absence. On this level, Pete is an integral part of how I maintain a connection to this other life, and our relationship is as much based on the photographs we make as in the deep personal connection we continue to develop. To stop photographing Pete would be in some way to let him go, and to a larger extent to let go of this second life.

RS: How did contracting HIV change your life and how does it manifest in your work and activism?

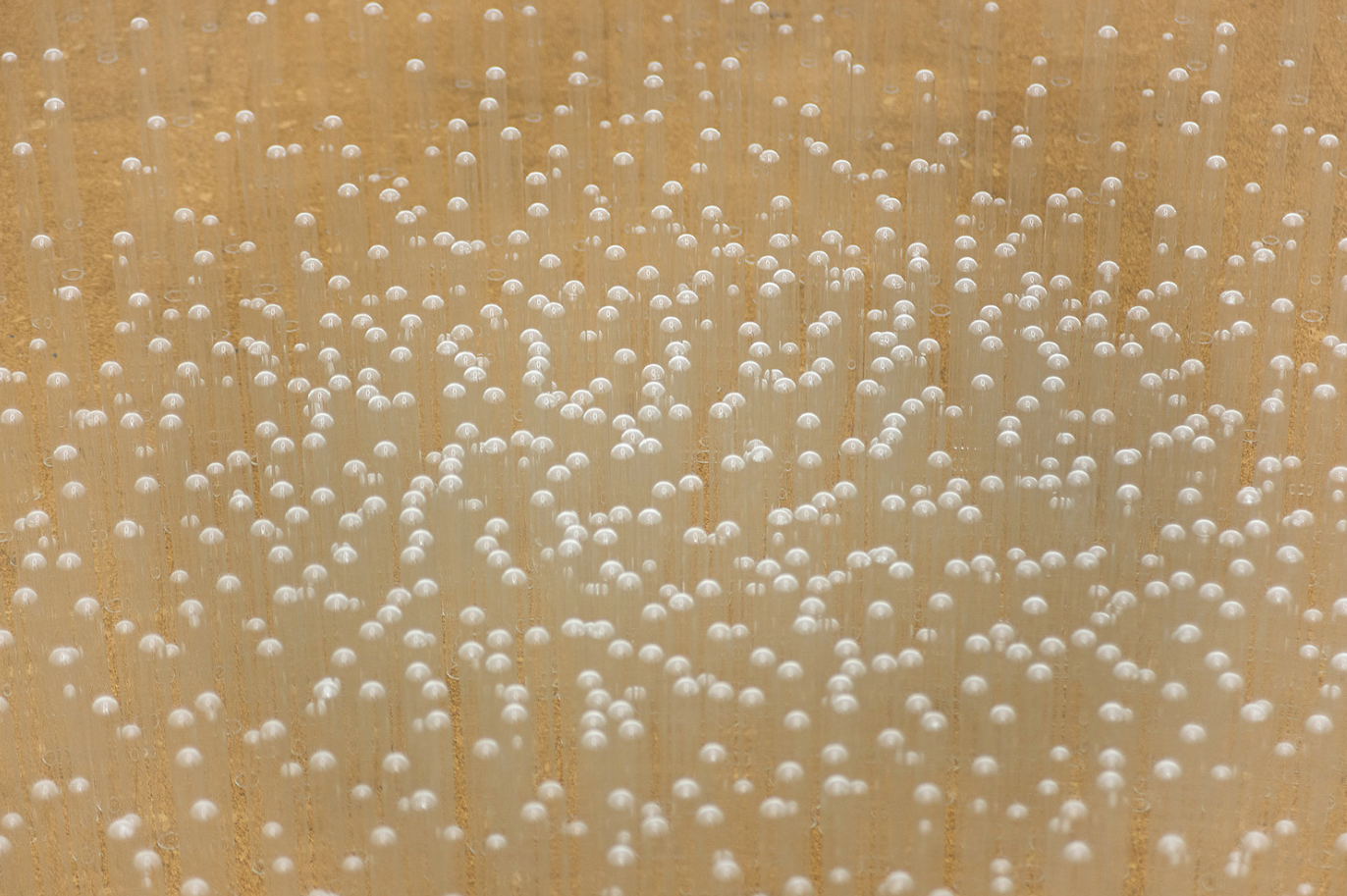

LB: For a long time I was unable to acknowledge how upended my life was after being diagnosed with HIV. It completely shattered the sense of self I had developed. I started graduate school at the same time I was coming to terms with the diagnosis, and when I arrived at the University of New Mexico I brought the shattered pieces of myself and began looking for a way to put them together again. I was extremely unwilling to openly discuss the impact all of this had on me. Instead, I began working with materials that would speak to the fractured sense of self I went with. I found my answer in a material I was becoming all too familiar with: glass test tubes. In this form they evoke a sense of surviving annihilation, but only just barely. The tubes are placed on the ground and secured in place with nothing but gravity. A breath too hard breath sends them all crashing down. Should the viewer dare draw near, they notice what appears to be residue in the bottom of each tube, now turned up right. In reality this is only an illusion. It’s only light. The power of light to attract and of glass to repel, this notion of tension created by these materials was not only a way for me to talk about and express what I was going through, but also became the catalyst for the bodies of work that followed.

Above: Untitled - Test Tubes

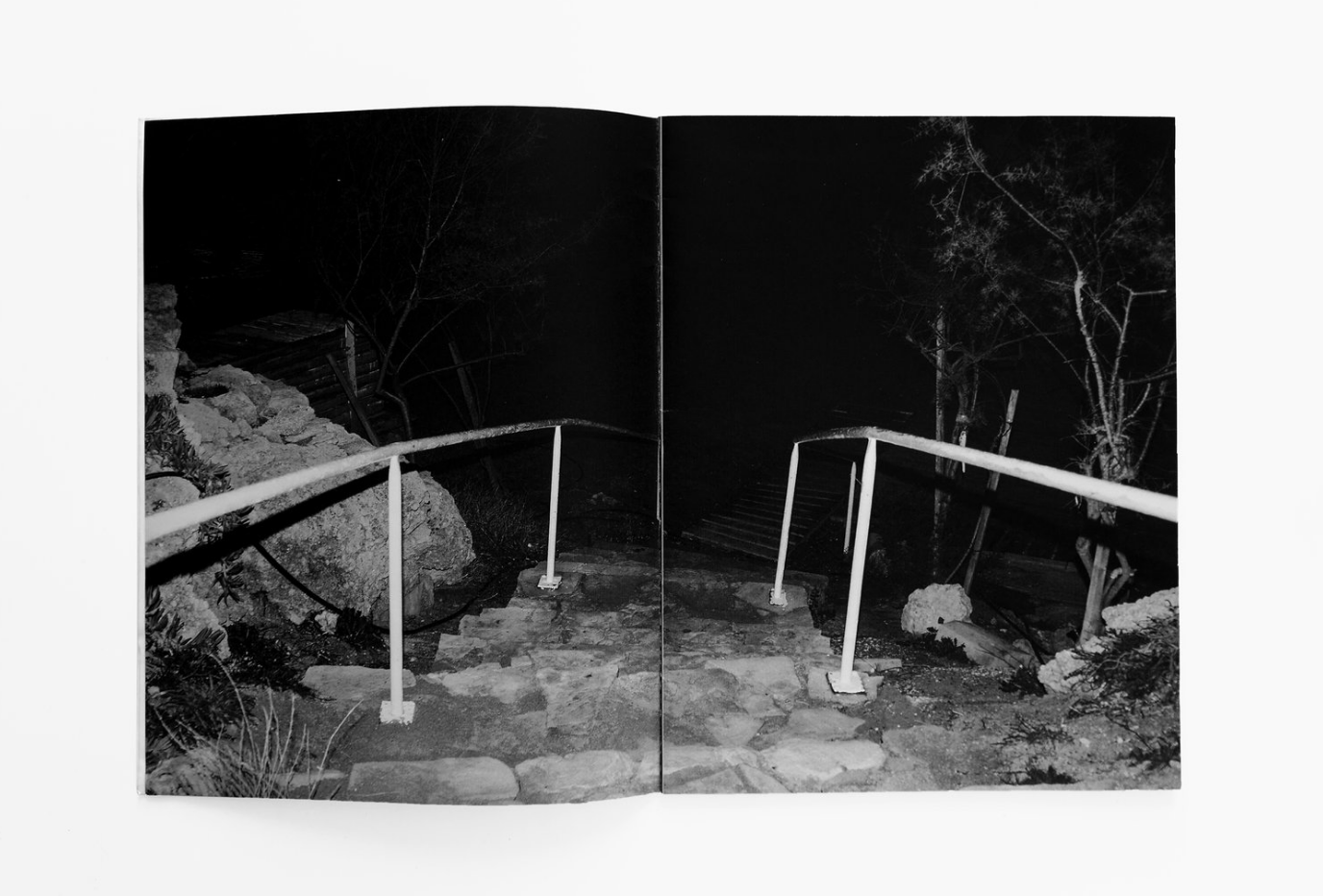

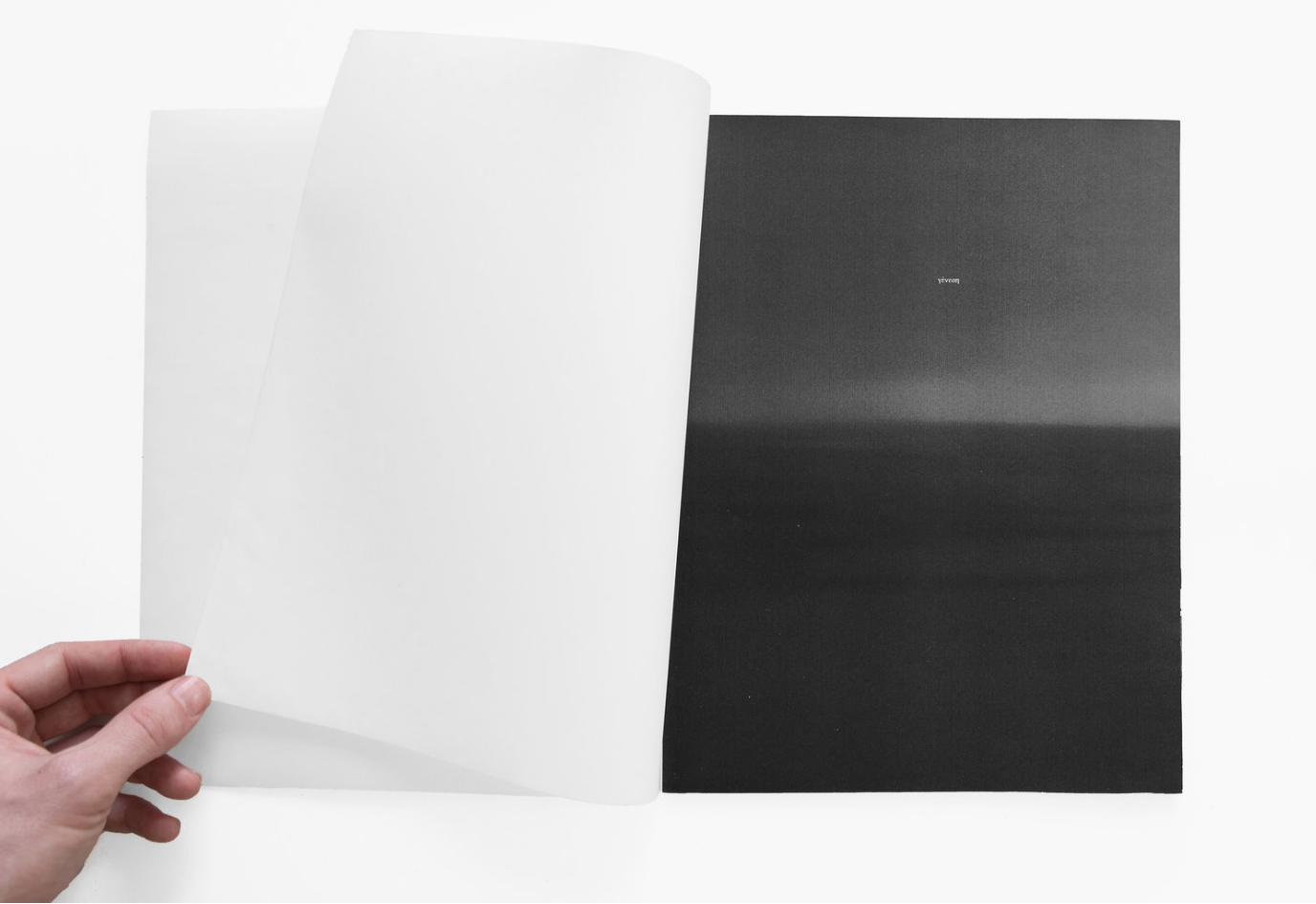

At the end of 2013, the official year of my diagnosis, I went back to Cyprus. It’s where I contracted the virus, and exists, in a way, as a beginning. The beach where I had the brief encounter that would change my life is the subject of a self-published zine titled Origin (in Greek the title is “Genesis”). The photographs documenting this beach at night are dark and grainy, and flashes of light illuminate only small portions of the area. The photographs are vague, occasionally difficult to read, and only offer the looker slight glimpses. Darkness acts as a barrier, the light from the camera flash existing as the only hope of breaking through, even if it is slight. When I returned to make the photographs, I wasn’t hoping to find that person there, but I was hoping to find some sort of closure. Of course I didn’t find it, that’s not how closure works. So instead I printed my photographs on a Xerox machine and made them into a small magazine, which is quickly reproducible and can with little effort be disseminated, one could say, virally. The Xerox prints are devoid of all interest in permanence or perfection. To me giving this document a form that will decay over time was, and perhaps still is, my best and only attempt to achieve a specific closure. With time comes the destruction of this memory.

Above: Origin

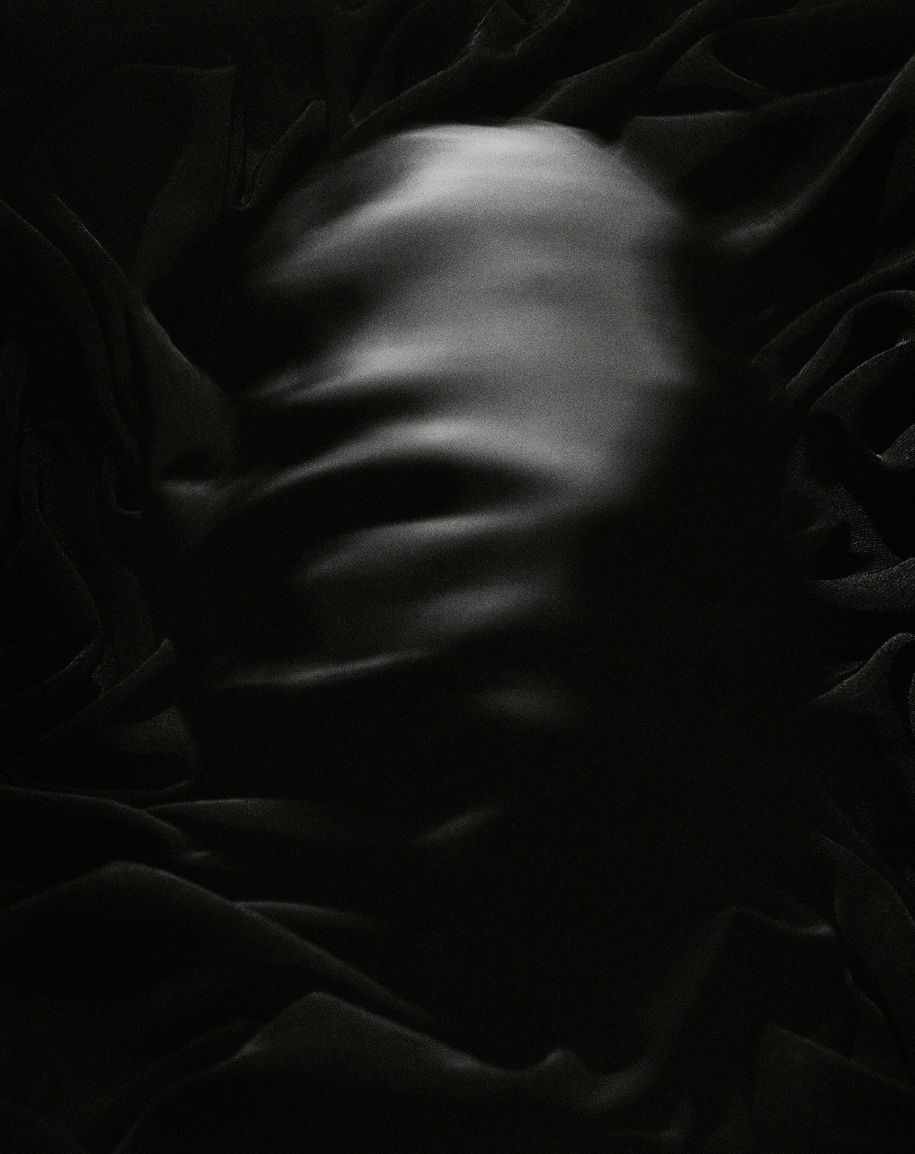

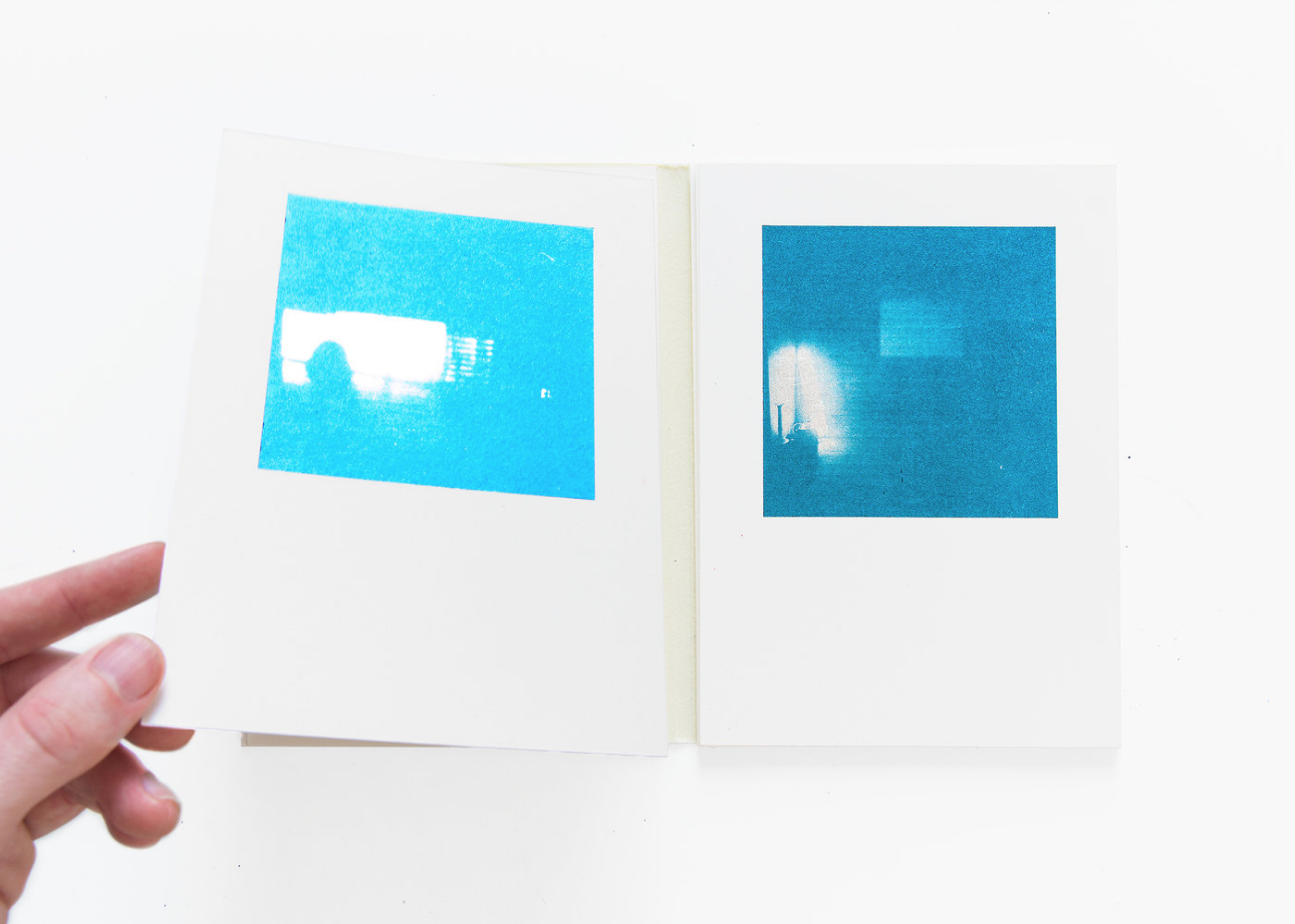

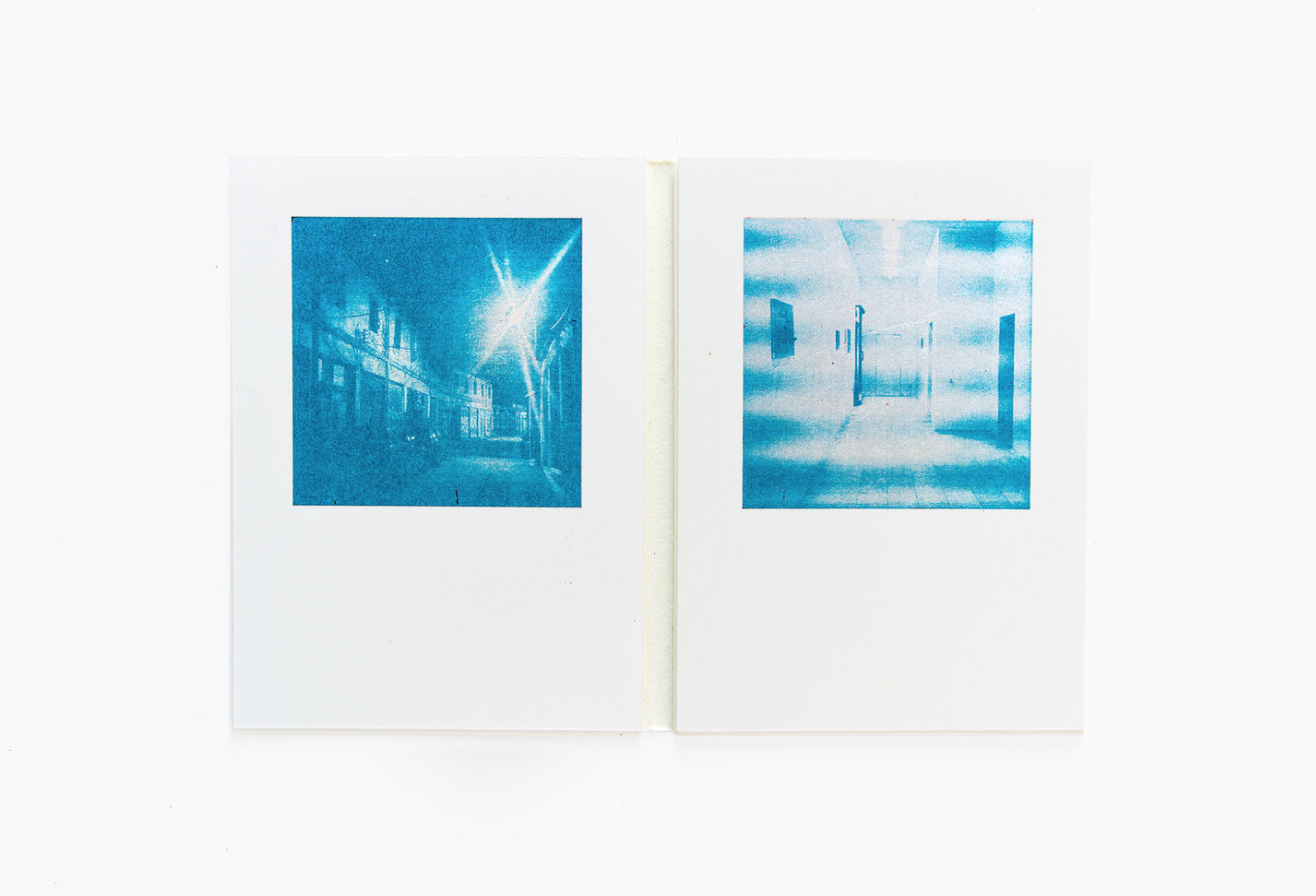

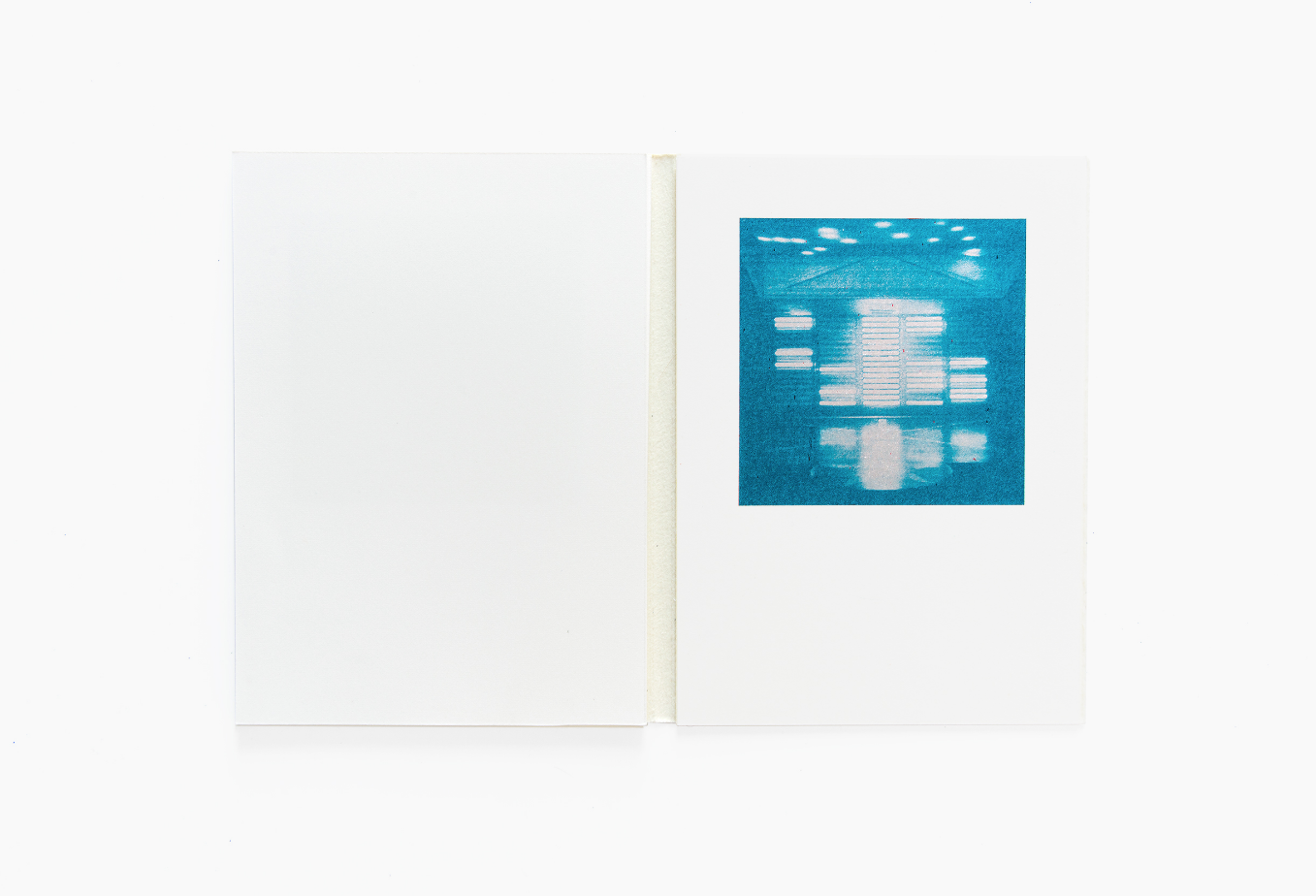

In the little folio of photolithographs titled Phantasma (in Greek the title is “Ghosts”), the viewer slowly turns each print over as ambient light reflects from silver leaf, illuminating their surfaces. The photographs transfigure shadows, reflections, landscapes, and people. Just as the light of our own existence flashes briefly on the cosmic timeline, so do the prints cast their light on the world and succumb back into darkness.

Making these works was formative for me, and while they in many ways serve the purpose of record and response to a struggle, they also serve a second life as part of my activism. When I speak about being HIV positive openly, I usually reference these works as direct products of this time and more importantly as illustrations for the story I am telling. Additionally, the more I let being HIV positive become a visible part of my life through activism, the less it became visible in any specific way within my own work. The echoes of it are still present, it’s always swirling around in my head somewhere and makes appears in my work in this way, but the amount of energy I expend on it has diminished significantly and allows me to think of other things… like photographs of Pete.

RS: What's the current situation in Cyprus in regards to LGBTQ issues and HIV awareness, and what position do you find yourself in to incite dialogue?

LB: I can only offer observations based on my own conversations and experiences, but the social and political climates are relatively conservative. People living with HIV are heavily stigmatized, and though many organizations continue to make strides for the rights and visibility of LGBTQ persons, the closet is still the norm for many. I am able to be publically vocal in Cyprus about living with HIV, but it’s not without acknowledging a certain privilege. I am not from this place and am able to be visible without running the same immediate risk of losing family, friends, jobs, and support networks (though this is not to say that as a queer person I haven’t taken this specific risk before). But this is a platform I now find myself on, and I would be remiss to have this opportunity in front of me – to be a voice – and never take it. Being visible is one of the first steps to fighting stigma. It is my hope that the story I tell with my work and with my actions will cause other voices to speak for themselves – I know I’m not alone in my desire for better visibility, recognition, and understanding.

RS: Installation has always been a part of your practice. What attracts you to work in both these mediums, and how do you feel they complement your work?

LB: When I think about my favorite pieces of art, literature, music, and film the common thread is that each transports me, allows me to suspend my own reality, and provides me the space to become absorbed in another world. This is all to say that I want to have an experience when I look at art. My work swings back and forth on a pendulum between photography and installation-based work. In an installation I feel like I can achieve a visceral response based on material and imposed space. With photographs though, I pull back, wanting instead to tell you a story. I am not entirely sure how to reconcile these two things (every attempt has been by my own self-criticism unsuccessful), but maybe they don’t need to go together. I think it’s enough to communicate well with one method, as long as it suits the intent.

RS: How do you make a living as an artist?

LB: Currently I work as a project manager putting together exhibitions for museums and galleries. Making an installation, making photographs, making anything really requires a certain amount of coordination, planning, and problem solving. In order to pull off a successful installation you need to have a plan, materials in place, people to help you, etc. The process for working through these problems was not something I learned on-site or was trained specifically to see or recognize. These skills came from trying to figure out tough problems in my own creative work in the studio. The best thing I received from my education was the empowerment to see and apply the broader lessons of studio and critique classes.

RS: What's next for you?

LB: After years of making pictures I find myself now with a small archive of photographs from Cyprus, New Mexico, New York, and various other places my life has taken me. I don’t want the archive to become a graveyard, so I periodically look through in search of photographs I liked but never new what to do with, or search for relationships I am only just now seeing with fresh eyes. My work has also been rather photo-centric for some time so I’m starting to feel the need to stretch some muscles with a new installation piece.