Q&A: Ksenia Nouril

By Rafael Soldi | October 9, 2019

Ksenia Nouril is an art historian, curator, and writer specializing in global modern and contemporary art. She is the Jensen Bryan Curator at The Print Center (Philadelphia, PA).

From January 2015 to September 2017, Ksenia was the Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives (C-MAP) Fellow for Central and Eastern European Art at The Museum of Modern Art (New York, NY). Prior to that, she was the Research and Editorial Assistant for the Thomas Walther Collection in the Department of Photography at MoMA, where she co-curated the 2014 exhibition Production-Reproduction: The Circulation of Photographic Modernism, 1900-1950.

Ksenia holds a BA in Art History and Slavic Studies from New York University and an MA and PhD in Art History from Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Her graduate studies were supported by the Dodge Fellowship at the Zimmerli Art Museum (New Brunswick, NJ). In March 2016, she organized Dreamworlds and Catastrophes: Intersections of Art and Technology in the Dodge Collection, which traveled to the Bruce Museum (Greenwich, CT) as Hot Art in a Cold War: Intersections of Art and Science in the Soviet Era (2018). As Guest Curator, she will open Stories About Ourselves: Ilya Kabakov and Viktor Pivovarov at the Zimmerli in November 2019.

Ksenia lectures widely and frequently writes for international exhibition catalogues, magazines, and academic journals, including ARTMargins Online, The Calvert Journal, Institute of the Present, OSMOS, and Woman’s Art Journal. She has published two books: Art and Theory of Post-1989 Central and Eastern Europe: A Critical Anthology (co-editor and contributor, MoMA/Duke University Press, 2018) and Stories About Ourselves: Ilya Kabakov and Viktor Pivovarov (editor and contributor, Rutgers University Press, 2019).

Rafael Soldi: Hi Ksenia, thanks for chatting with us.

Ksenia Nouril: Thank you for inviting me. I’ve enjoyed following the Strange Fire and appreciate the opportunity to share my work with your readers.

RS: Prior to becoming the Jensen Bryan Curator at The Print Center in Philadelphia you were a Contemporary and Modern Art Perspectives (C-MAP) Fellow at The Museum of Modern Art. What are some of the differences, challenges, and joys of curating at a large institution vs. a small institution?

While every institution is unique, you could say that I’ve worked in three general types of over the last ten years—a major metropolitan museum, a university art museum, and a non-profit gallery.

While pursuing my graduate studies at Rutgers, I worked for several years at its Zimmerli Art Museum, which employs about 30 people and primarily served the academic community. All of my curatorial projects there stemmed from one collection: the Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union. At the Zimmerli I really cut my teeth on exhibition making from start to finish and faced the challenge of interpreting a collection that is fairly opaque to the average viewer.

In 2014, I began working at MoMA in both in the Department of Photography and the International Program. While there were many immediate and tangible results from the intellectually rigorous work my colleagues and I did to foster international collaborations, it was just one piece of MoMA’s gigantic puzzle. At such a big institution, your role can be siloed, and despite many resources and benefits, you still can face certain limitations. You play the long game.

After finishing my PhD and a book for MoMA, I found myself wanting a new kind of challenge. In January 2019, I joined The Print Center, a nonprofit in Philadelphia dedicated to expanding our understanding of printmaking and photography as vital contemporary arts. There, I curate seven exhibitions per year; organize three seasons of public programs for all ages; manage a publication program; and oversee the ANNUAL International Competition now in its 94th year. We are modest but mighty. Doing a lot on a small budget requires energy and ingenuity. Ideas need to be scalable. Partnerships are pivotal both for execution and impact. Working with shorter timelines can be stressful, but it also allows us to be nimble. Our ability to be reactive means that we remain relevant, responding to developments in our field and the needs of our communities.

RS: As a curator—thus a gatekeeper—what values are you bringing with you that you hope will define your tenure at The Print Center?

KN: The Print Center was founded as The Print Club in 1915 by artists for artists, by collectors for collectors. We gained non-profit status in 1925, opened our first photography exhibition in 1933, and consistently engaged with women artists, artists of color as well as artists of diverse religions since our early days. Nine out of our ten directors have been women, including our current director Liz Spungen. In 1960, we started Prints in Progress, a program that brought art education into the Philadelphia public schools. Today, we run the Artists-in-Schools Program (AISP), which puts teaching artists in high school classrooms around the city up to twice a week during the academic year. This history was something that attracted me to this job. Formally, I approach print as an expanded medium—inclusive of all printed matter as well as digital interventions. Conceptually, I am interested in the individual and collective stories art tells. While I don’t work exclusively with living artists, my practice is artist-driven, so my instinct is to prioritize the artist’s voice. I think my role as a curator is to uplift and amplify these voices in chorus with those of the many communities we serve. Although an international voice in print, I want to think about how The Print Center can better reflect its sitedness in Philadelphia—the so-called bedrock of American democracy—and in Center City—a historically elite but transient neighborhood. Print is ubiquitous, so we should be, too.

The Politics of Rhetoric, 2019, Installation view of work by Bethany Collins and Didier William, The Print Center. Photo: Jaime Alvarez

RS: An interesting challenge that most curators face at some point is inheriting exhibitions that they did not originate but must execute. How do you bring your voice to a project that wasn’t yours to begin with?

KN: Starting a new job—and, in my case, also moving to a new city—was exciting but also overwhelming, so I was grateful to have inherited a few exhibitions throughout 2019 and 2020 from my predecessor. Each was in a different stage of development, so I was able to jump in and shape the final results. That’s how we met! I was handed your exhibition Rafael Soldi: CARGAMONTÓN in the form of two large StrongBoxes on my first day. While the checklist and layout were complete, I had to write the wall text, based on research previously compiled and my close looking at the works themselves.

Similarly, The Print Center already had been working with James Siena to exhibit new prints he pulled while in residence at three universities in 2017-2018. At the end of a studio visit with James—during my second week on the job—he showed me a couple of his typewriter “drawings,” and I immediately had the idea for New Typographics: Typewriter Art as Print. This exhibition, which filled a gap in our exhibition calendar, reframed the global phenomenon of typewriter “drawings” as prints based on the mechanics of their production and included work by Elena del Rivero, Lenka Clayton, and Allyson Strafella as well as loans from the Sackner Archive of Visual and Concrete Poetry.

I consider the projects I inherited as gifts because they set up parameters that I can work with as well as push against. When presented with a scheduled solo exhibition of photographs by the Texas-based artist Keith Carter made in the Walt Whitman archives at Duke University, I knew I wanted not only to contextualize the exhibition within the writer’s relationship to the greater Philadelphia-Camden region but also pointedly address his complex and often mercurial views on race, class, gender and sexuality. I seized the chance to bring artist Jonathan Lyndon Chase, writer Lavelle Porter, and Whitman at 200 Curator Judith Tannenbaum together in a panel discussion reflecting on this so-called bard of democracy and how we can reckon with history through the visual and literary arts.

Being able to put my own spin on inherited projects has been a humbling experience, too. It speaks to the collective work—seen and unseen—that goes into exhibition making. I’m grateful to be working with colleagues both within and outside my institution committed to equity, diversity, and inclusion.

The Politics of Rhetoric, 2019, Installation view of work by María Verónica San Martín, The Print Center. Photo: Jaime Alvarez

RS: Tell us about your current exhibition The Politics of Rhetoric. How did this come about and why is now the right time for this show? [The Politics of Rhetoric is on view Sept. 13 – Nov. 16, 2019 at The Print Center]

KN: The Politics of Rhetoric is a group exhibition that brings together new and recent works rooted in print that address the inherent biases in everyday language. Delving into a variety of personal and public archives, artists Bethany Collins, Sharon Hayes, Sarah McEneaney, Keris Salmon, María Verónica San Martín, and Didier William draw our attention to how those in power can manipulate words and phrases, so that they become racist, sexist, and/or classist. The exhibition’s title is inspired by rhetoric—the ancient art of discourse that plays to the logos (logic), pathos (emotions) and ethos (morals) of the listener. This exhibition developed rather quickly in reaction to several things. First, I consistently hear from artists about how their practice has changed since the 2016 election of Donald Trump as the President of the United States. I started seeing the word rhetoric come up more often, especially in the media. I typically used the word to denote a certain vocabulary used in a conversation; however, my research revealed that it was so much more. Rhetoric influences not only the choice of words but also their structure within sentences. Everyone uses rhetorical devices every day to convince others—and ourselves—of things. Second, in conjunction with the Keith Carter exhibition I inherited, I wanted to make a space to openly think about the hierarchies within the archive. What is kept, and what is discarded? Who makes these choices and, in doing so, who is silenced? Working in print, photography, painting, video and performance art, the artists in this exhibition explore the uses and abuses of rhetoric as well as the subjectivity of the archive in texts pulled from primary sources, including audiotapes, musical scores, newspapers, and the records of southern American plantations.

RS: Language is so important, and it is inherently political, as your show aims to explore. Who has the privilege to have a voice, and who is voiceless influences how the world around us is built. What are some ways in which artists in the exhibition are exploring these issues?

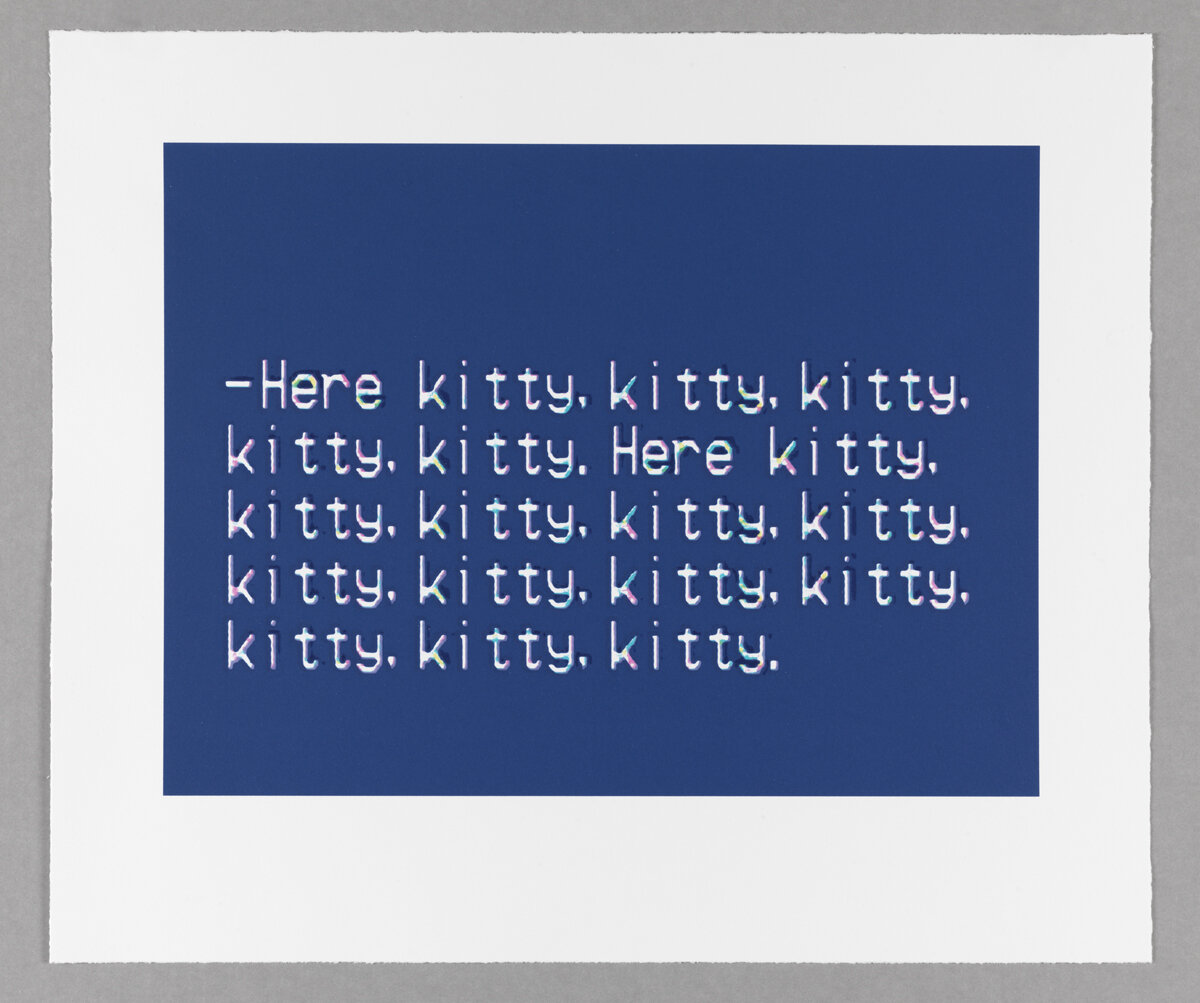

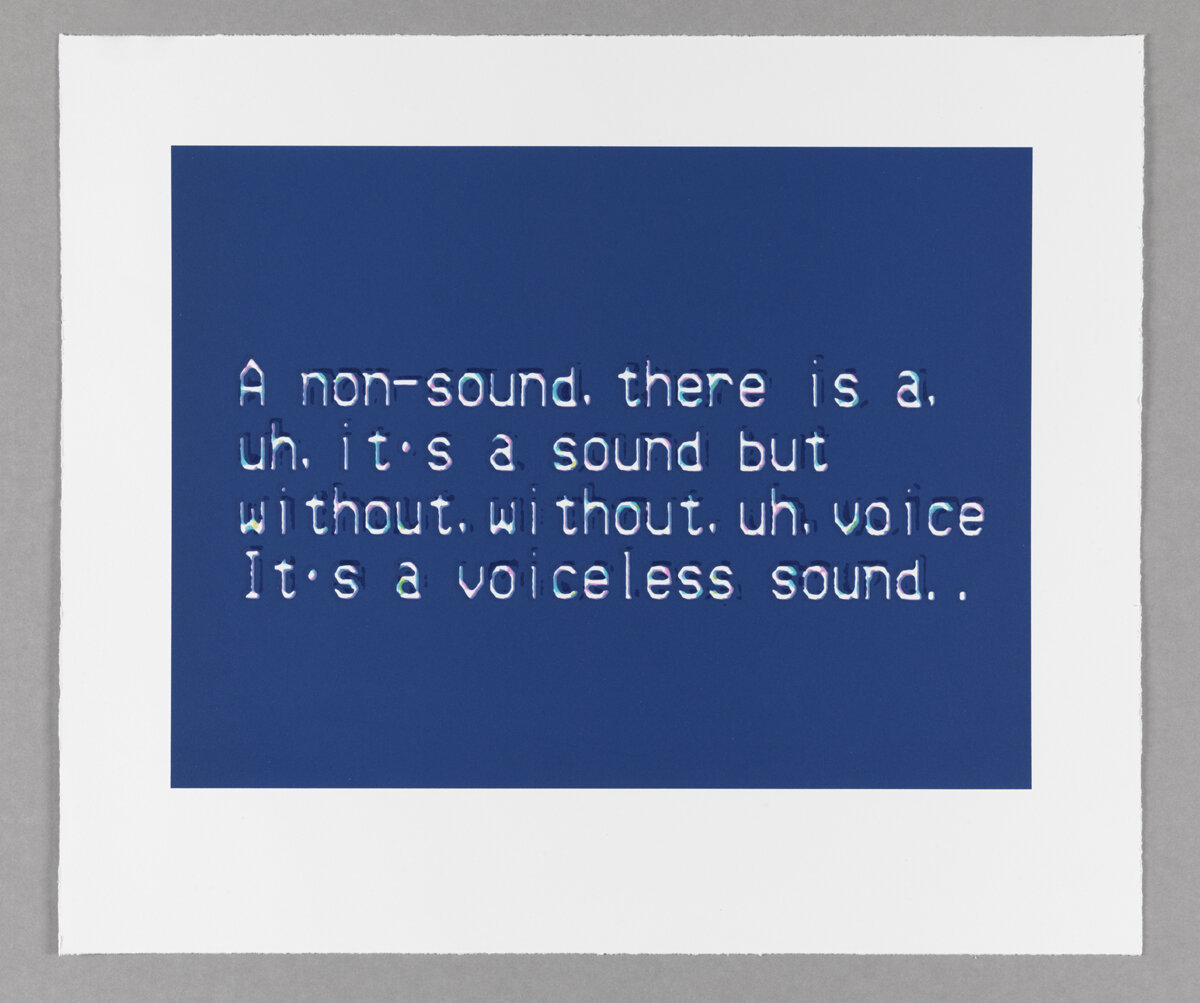

KN: For her suite of five color plate lithographs entitled The Nature of the Beast (2019), Sharon Hayes culls text from a transcript of an audiotape found in the archives of U.S. Congresswomen Bella Abzug (1920-1998), a passionate feminist and staunch supporter of equal rights in the 1970s. In spite of her leadership in these areas, she faced criticism for her thick New York accent and flamboyant personality. The audiotape is a record of a voice lesson Abzug was forced to take to correct this perceived impediment. Its gendered language exposes the power dynamic between a male teacher and female student and raises questions around what Hayes calls “political voice” and how we speak “in and through politics.”

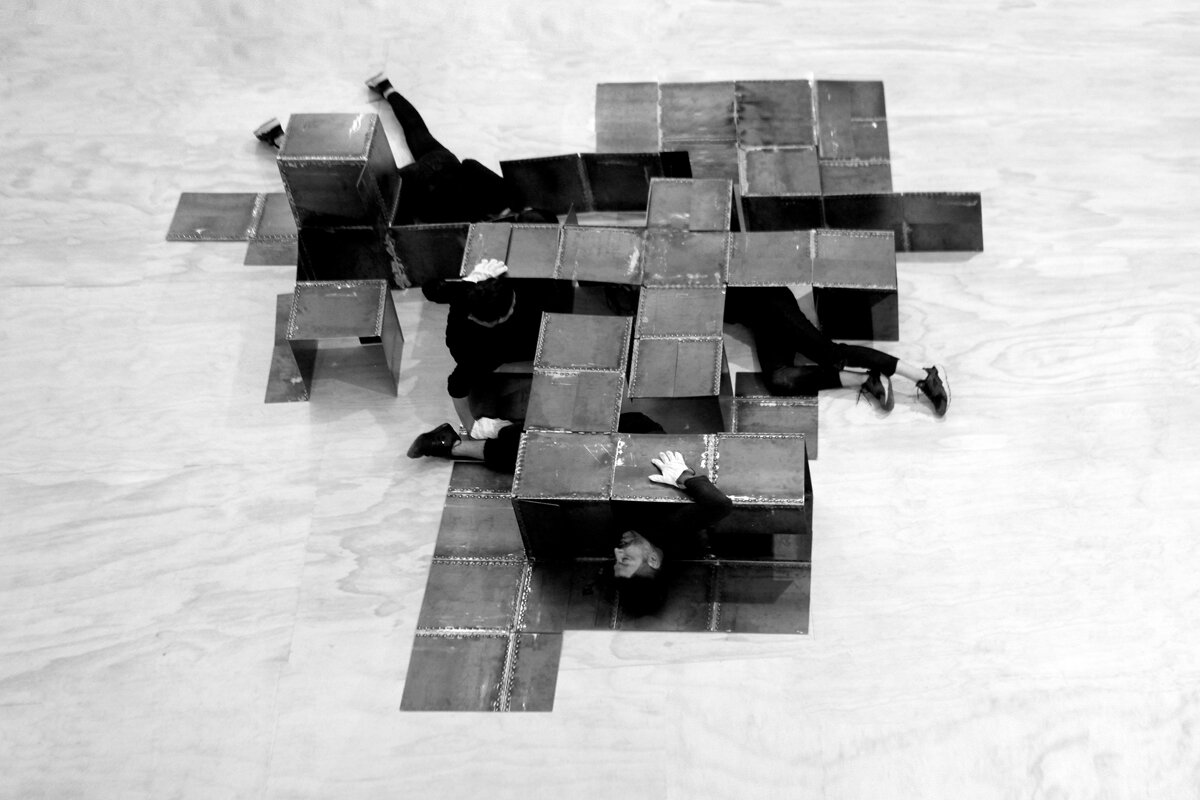

Audiotapes are also the foundation of María Verónica San Martín’s ongoing research-based project Colonia Dignidad, which meditates on the human rights violations committed in an isolated settlement established in 1961 by Nazis, who relocated from Germany to southern Chile. San Martín gained access to the recordings made shortly after the 1973 coup d’état, describing the colony’s collaboration with the infamous Pinochet regime. In reaction to this, San Martín produced a number of artist books, each made from over thirty pounds of steel, which are both a prop and a costume for a performance based on the transcriptions one of the audiotapes.

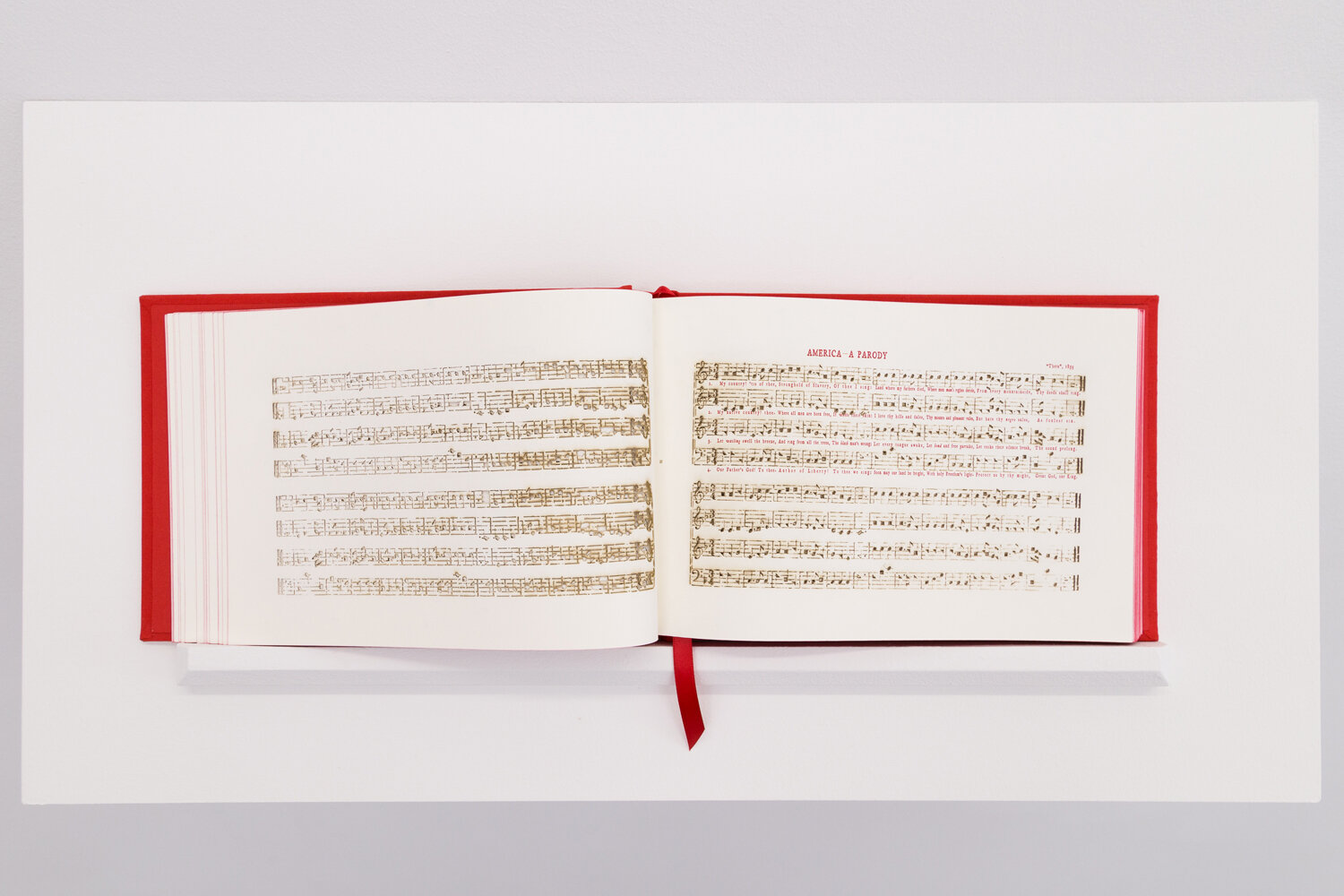

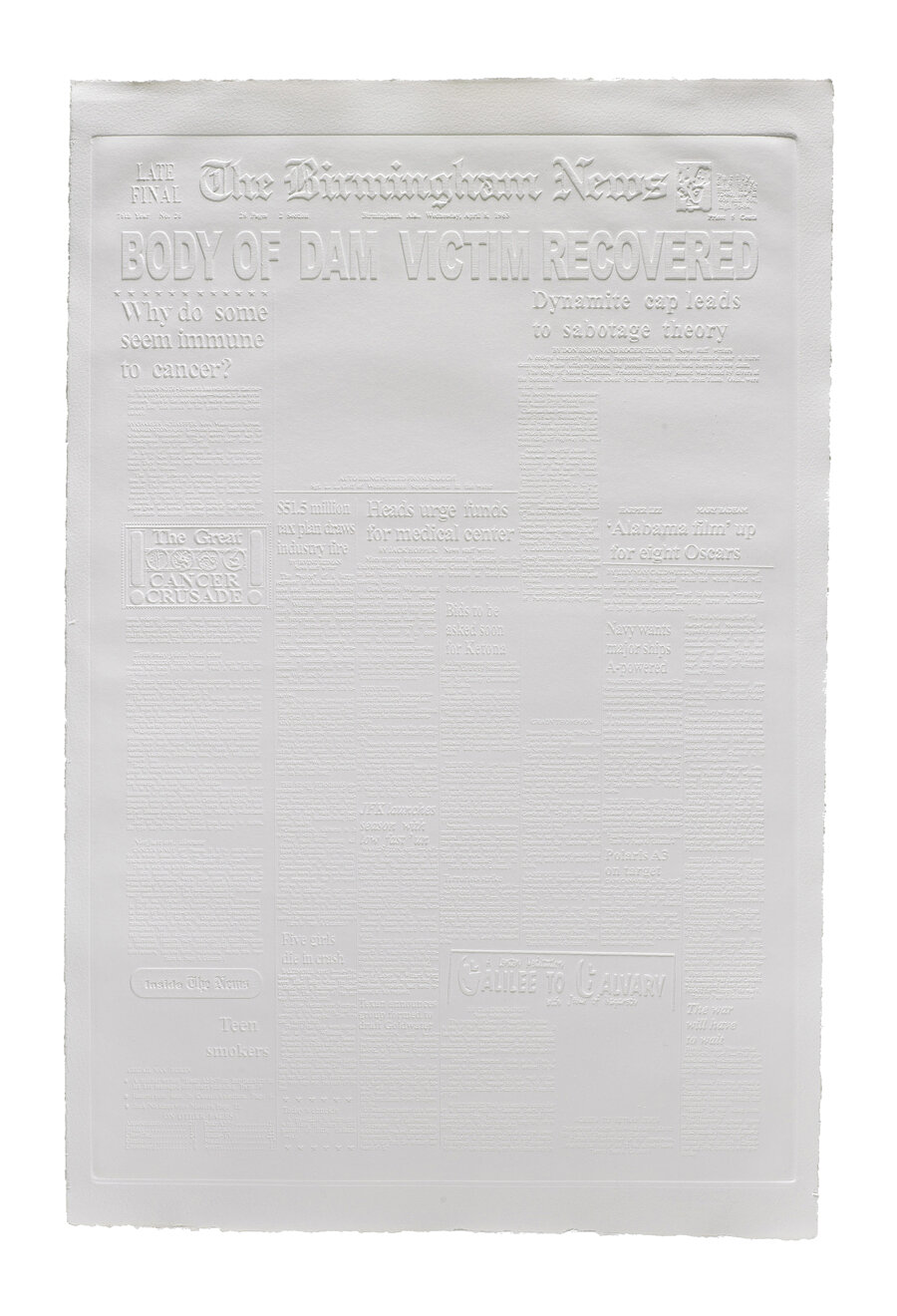

A newspaper—a form of printed matter—becomes source material for Bethany Collins in April 8, 1963 (2015). Using blind embossment, a printmaking technique that renders text with pressure but not ink, she reproduces of front page of The Birmingham News. Her research into the newspaper’s archive revealed how stories of the Civil Right Movement were suppressed from the headlines, silencing the voices of African Americans and their allies in their struggle for equality. The exhibition also includes her artist book America: A Hymnal (2017), which comprises 100 versions of the patriotic song “America,” whose melody has been used with different lyrics in support of various causes. Collins emphasizes these differences by eliminating the musical notations with a laser cutter, thus questioning what “America” means today.

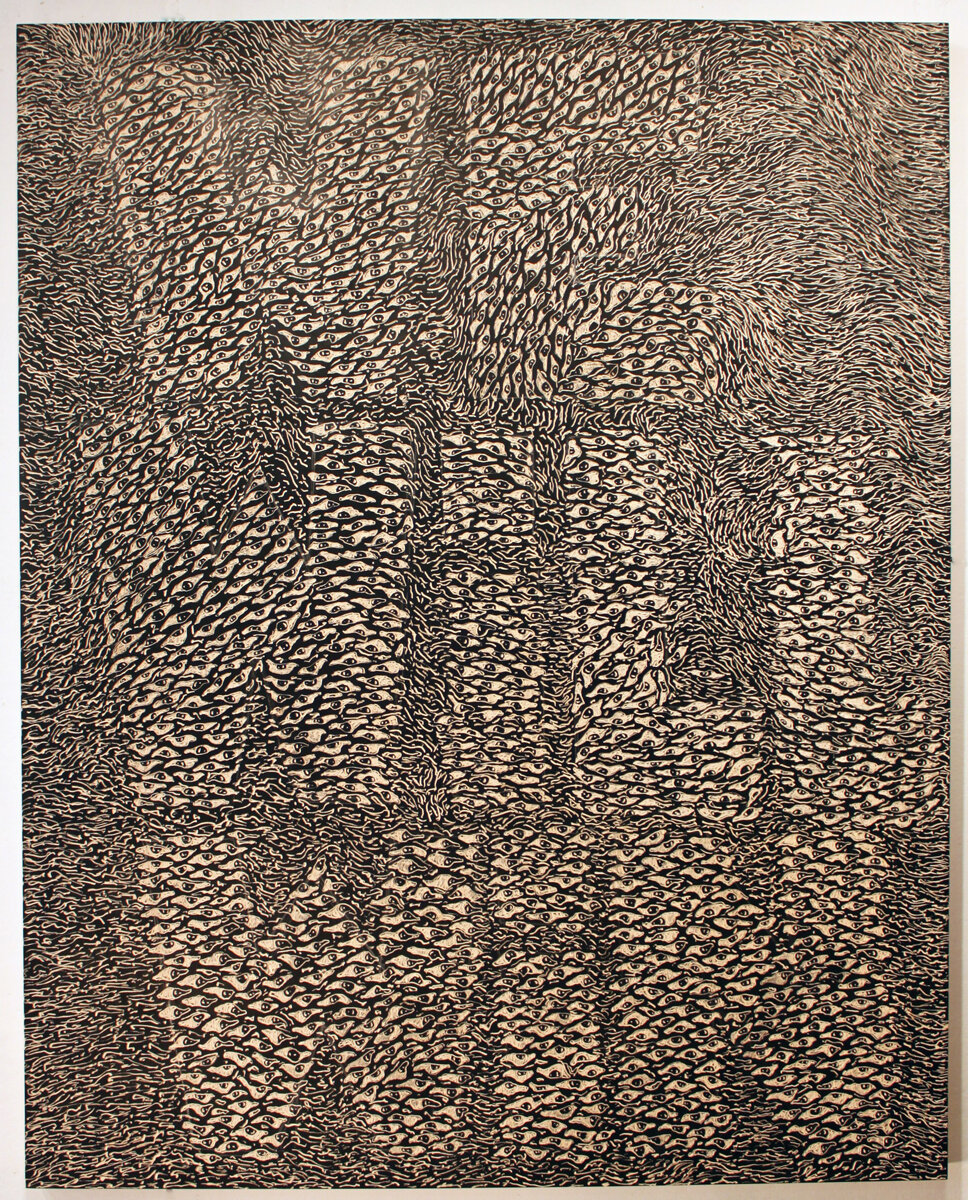

Other work in the show is more pointed in its address of rhetoric. The phrase “We will win” used by Didier William in both a painting and a print has a long history as a rhetorical device. This phrase has been adapted by numerous groups with divergent agendas—from athletes in the Civil Rights era to students in the U.S. Naval Academy. It is a motto of the Black Lives Matter movement and has been proclaimed in speeches by politicians, including Donald Trump. Much like in Collins’ America: A Hymnal, William harnesses its multiple meanings to challenge what “winning” looks like. His works reinforce the immense power but also ambiguity of these and similar platitudes in contemporary society.

The Politics of Rhetoric, 2019, Installation view of work by Keris Salmon, The Print Center. Photo: Jaime Alvarez

RS: Many artists in the exhibition work around archives, either visiting historical ones or creating new ones. Why do you think artists working with the polarization of language are naturally gravitating toward archives? What’s the connection here?

KN: The archive, broadly conceived, is what ties all the works together.

While the archive operates differently in works across the exhibition, I’d say it is a prevalent trope because we find ourselves in a critical moment of global reckoning with history. Histories that have been suppressed by hierarchies founded upon the patriarchy and colonialism are not unwritten. They exist—held within those whose daily lives are marked by biases and injustices. They are uplifted and amplified in the work of artists like those in The Politics of Rhetoric.

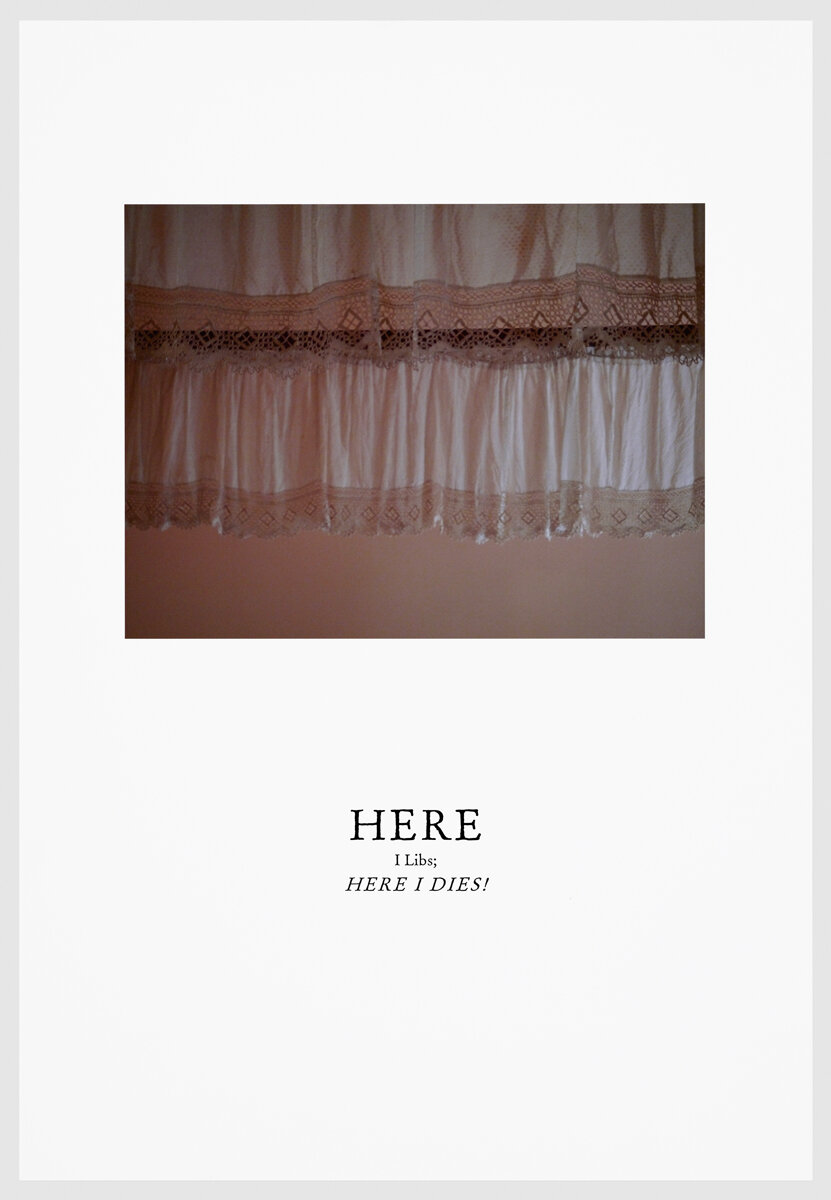

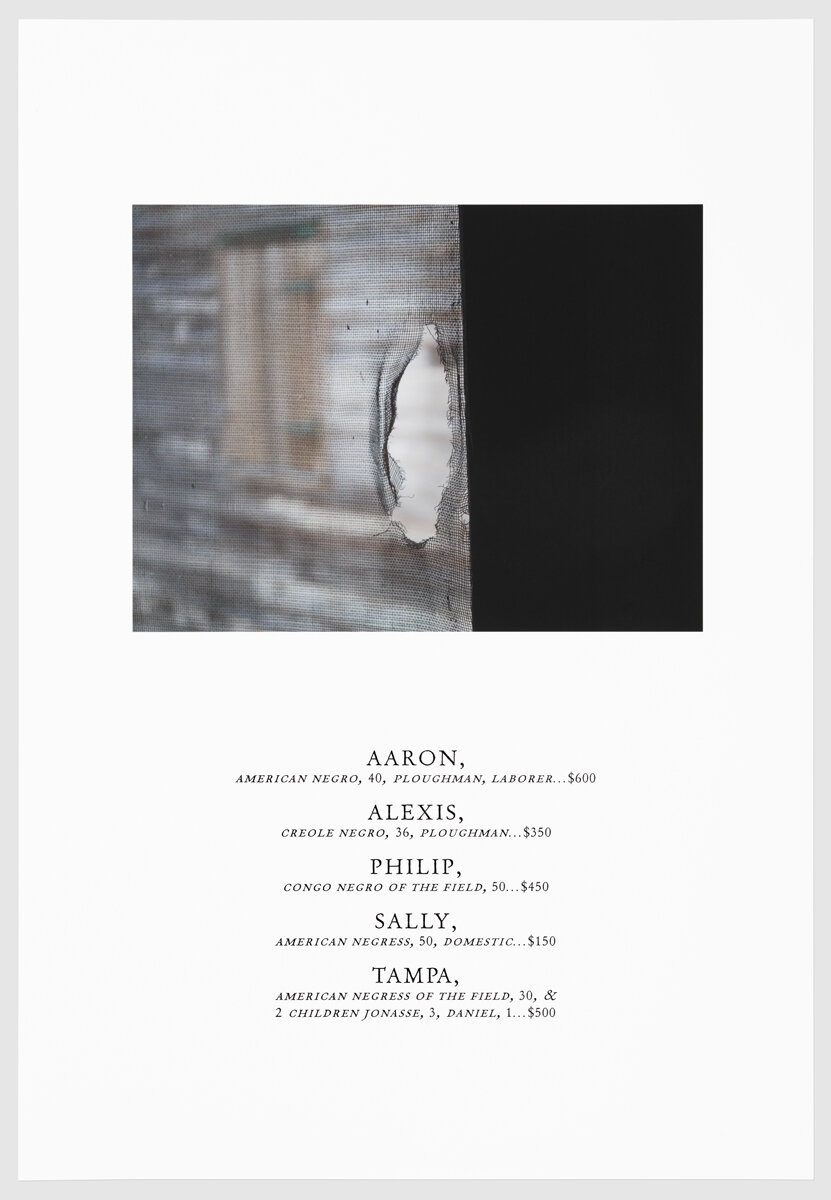

Some of the artists in the exhibition, like Keris Salmon, use preexisting archives. Her series “We Have Made These Lands What They Are: The Architecture of Slavery” (2016-2017) comprises 18 prints that juxtapose a photograph with a letterpressed quotation taken from the archives of antebellum plantations across the southern United States. The voices of the enslaved and enslaver come together in this work, which pictures the more banal elements of everyday plantation life, like wooden benches in a schoolhouse or the roughly patinated surfaces of wrought-iron fences.

Other works embody a stronger element of self-archiving. Sarah McEneaney creates an archive within an archive in her ongoing series “#wehavenopresident,” which began in May 2016 by defacing images of Donald Trump reproduced in The New York Times and The Philadelphia Inquirer. After completing one of her drawings, McEneaney photographs it with her iPhone, uploads it to her personal Instagram account, and hashtags it. The work puts these altered images back into circulation but on an alternative platform.

The Politics of Rhetoric, 2019, Installation view of work by Didier William and Sharon Hayes, The Print Center. Photo: Jaime Alvarez

RS: What themes or exhibitions are you working on for the coming years at The Print Center?

KN: Next up in January are three solo exhibitions from the 94th ANNUAL International Competition. Open to any artist with work incorporating an element of printmaking or photography, this juried competition is nearly as old as The Print Center. While I’m not involved in the jurors’ review, I select these exhibitions once they announce the ten finalists. This is exciting because the competition brings some of the most conceptually relevant and technically cutting-edge practices to the fore. These exhibitions will be followed by our spring and fall 2020 seasons dedicated to the themes of the built environment, ecology, and migration. For the future, I’d like to develop projects that incorporate public art components and would love to find any excuse to return to the topic of my dissertation, which looked at the phenomenon of the historical turn in contemporary art from Eastern Europe. I think that transition from communism to capitalism provides many transferrable lessons and could be expanded geographically to consider other historical moments of change.

RS: Artists always want to know how to get in front of curators, and there is no one answer to that question. So let me ask you this, once an artist gets your attention, what are some attributes and tangible actions that make you want to get to know them better or grow that working relationship?

KN: I put a lot of stock into networking. It’s how great projects come to fruition. It’s very important to get out there and meet people in both social and professional settings. You never know whom you’ll meet, so you need to introduce yourself to each person as if they might be your next collaborator. This means you should have a business card or some other way of easily connecting via email and/or social media. Although some people advise against it, I don’t shy away from Instagram and, actually, do a lot of looking and corresponding via posts, stories, and direct messages. We’re on our phones so much (too much) these days, so it doesn’t take a lot of effort to send someone a quick “thank you” email for a meeting or a studio visit. It also makes keeping in touch a lot easier. If we’ve met, I appreciate occasional and succinct updates. I keep track of those things. Don’t get me wrong—I don’t respond immediately to every email, but if it is not filtered as spam, I will acknowledge it, even if briefly, and you should, too. Communication is critical for any collaboration, so I’m more eager to work on a project if I know you’re a reliable communicator. This engenders mutual respect for time, expertise, and labor.

RS: What are you obsessed with right now?

KN: I have a seven-year-old French bulldog named Lambchop and am obsessed with dogs, honing a specific interest in the depiction of dogs in art. With Lambchop and my husband, I’m exploring Philadelphia, which is a necessary but also welcomed obsession, now that I’ve been here already for almost a year. While I visit a lot of cultural institutions thanks to my job, I don’t always have the luxury of downtime to see what else the city has to offer. We’ve started to make a slow but concerted effort to visit the many green spaces in and near the city, spending Sundays in Fairmount Park or hiking along the Wissahickon Creek. I’m obsessed with reminding myself of, although not always practicing, a work/life balance.

RS: Thank you, Ksenia!

KN: Thank you, Rafael, Strange Fire Collective, and everyone out there who took the time to read this interview!