Q&A:Kristine Thompson

By Abbey Hepner | Thursday, May 17th, 2018

Kristine Thompson is an artist and educator working primarily in photography. Her work considers how contemporary photographic imagery circulates and addresses representations of death, memorial practices, and mourning. She received her B.S. in Education and Social Policy from Northwestern University and her M.F.A. in Studio Art from the University of California, Irvine. She is currently an Assistant Professor in the School of Art at Louisiana State University.

Thompson is the recipient of several awards, including a D.A.A.D. Fellowship in the Arts, which facilitated a year-long project in Germany, and an Investing in Artists Grant from the Center for Cultural Innovation. Her work will be featured in solo exhibitions in 2018 at Antenna Gallery in New Orleans, Texas Woman’s University in Denton, TX, and the Cecilia Coker Bell Gallery in Hartsville, SC. Other recent exhibitions include Commonwealth & Council, Los Angeles; the Armory Center for the Arts in Pasadena, California; the Colorado Photographic Arts Center in Denver; and School 33 in Baltimore.

She also served for several years as a curator at UCR/California Museum of Photography, and she continues to initiate independent curatorial projects. Most recently, the exhibition After Life was hosted by the Luckman Gallery at California State University, Los Angeles.

Kristine Thompson's series "Images Seen To Images Felt" will be featured alongside 21 other artist's work in the exhibition "Addressing Power," opening in Albuquerque, New Mexico on June 1st. The exhibition focuses on issues of social change and is hosted by Creative Advocacy, an organization that Abbey co-founded in 2016.

AH: Thanks for taking the time to talk with me Kristine. You received your M.F.A. in Studio Art from the University of California, Irvine and your undergraduate degree from the School of Education and Social Policy at Northwestern University. Tell me about your path and what inspired you to make work about loss, mourning, and history through photography and sculpture.

KT: Hi Abbey--Thanks for looking at and thinking about my work.

It was a bit of a meandering path for me before I discovered art. I went to Northwestern University initially to study journalism. I had a work study job in the art department and quickly became enamored with that community. I took my first darkroom-based photo class and I was hooked. I ended up in the School of Education and Social Policy where I was able to craft a major with classes in art, sociology, art history, education, and art policy. I recently revisited some of the negatives from that first photo class. They were photos from an AIDS March on Washington that a friend and I attended in 1996. It was the last time the Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt could be shown in one piece; it stretched from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial. I photographed everything that weekend: pieces of the quilt, the various marches and demonstrations, candlelight vigils, and a political funeral I witnessed when an activist threw his lover’s ashes onto the lawn of the White House. It struck me that even in those first photographs, I gravitated to loss and memorialization as subject matter. While I was in college I volunteered at a non-profit organization in Chicago that provided health care and social services to people living with HIV/AIDS. I was around patients who were coping with serious illness, and many of those that I became close to passed away. All of that definitely found its way into the work I was making. Death and mourning became a continued focus of my work in graduate school. UC Irvine was a very interdisciplinary and conceptual program. I had amazing teachers who encouraged us to experiment materially.

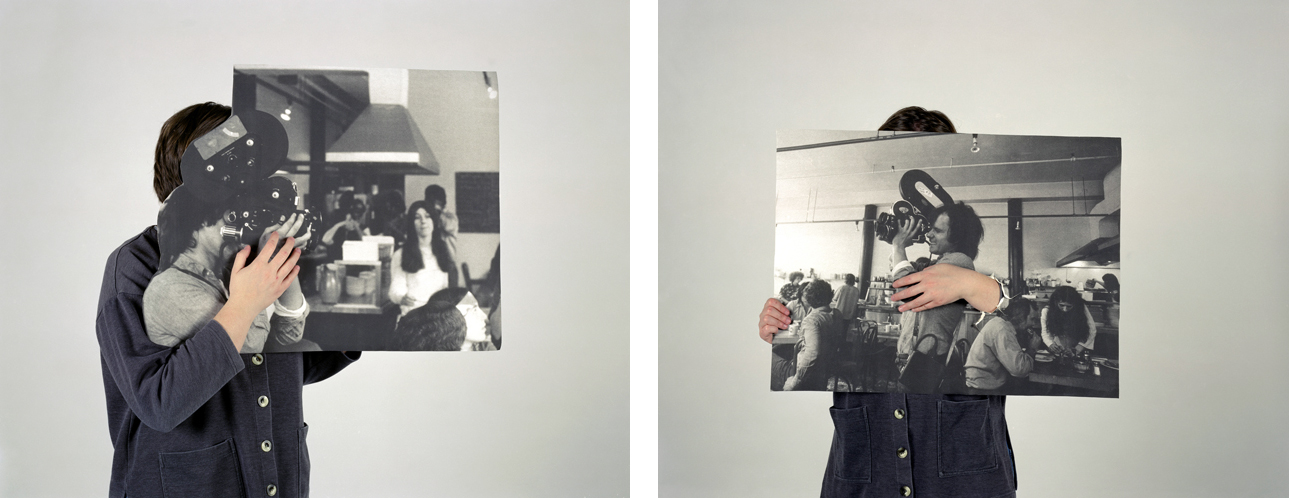

AH: I am interested in your projects Wanderer, (Not) Knowing Felix, Projecting, and Having Been There. They all reflect on artistic legacies and the research that you did to better understand the work of a few different artists. Can you talk about these projects, the kinds of questions you are asking, and how you are attempting to embody their work?

KT: There were a lot of questions driving those projects. How do we remember those who are no longer with us? How do we grapple with the legacies of artists we admire? How can we move beyond the weight of that admiration and insert our own voices? What kinds of conversations might I have, or want to have, with these people if they were alive and I could sit across from them? How can I engage ideas of sentimentality and tenderness in a way that feels sincere? How can I stage a photograph that allows for a kind of fantasy of going back in time?

(Not) Knowing Felix was the first body of work that tackled those ideas. Felix Gonzalez-Torres was the first artist whose work I was initially confounded by and ultimately smitten with. I love how he used everyday materials and imbued them with political and emotional content. I love the act of caretaking and the potential for disappearance built into the way his work is exhibited and sold. I love the affection he had for his partner Ross. In the series, I interacted with pieces of his that I obsessively collected from various museums and galleries over the years.

Projecting and Having Been There came after, and the work expanded to include other deceased artists and writers who often foregrounded their bodies or their subjectivities in their work. My interactions with the artists and their work gradually became more physical, more overtly (and sometimes awkwardly) tactile. I also eventually shifted from photographing primarily in the studio to photographing in locations where certain artists lived or worked. This on-site exploration was definitely true of the work I made in Germany. I was looking at artists who worked during very different historical moments and wondered how their legacies might still be felt in the cities where they once lived or worked. I spent time in Greifswald where Caspar David Friedrich lived and where these murals now exist—painted in his romantic style—in the most unromantic locations. I also visited Köln, where August Sander had his studio, and Kassel, where Joseph Beuys planted 7,000 oak trees in the early 1980s that have completely transformed that landscape. By walking in these artists’ footsteps, I was able to visit locations that I otherwise may have never experienced.

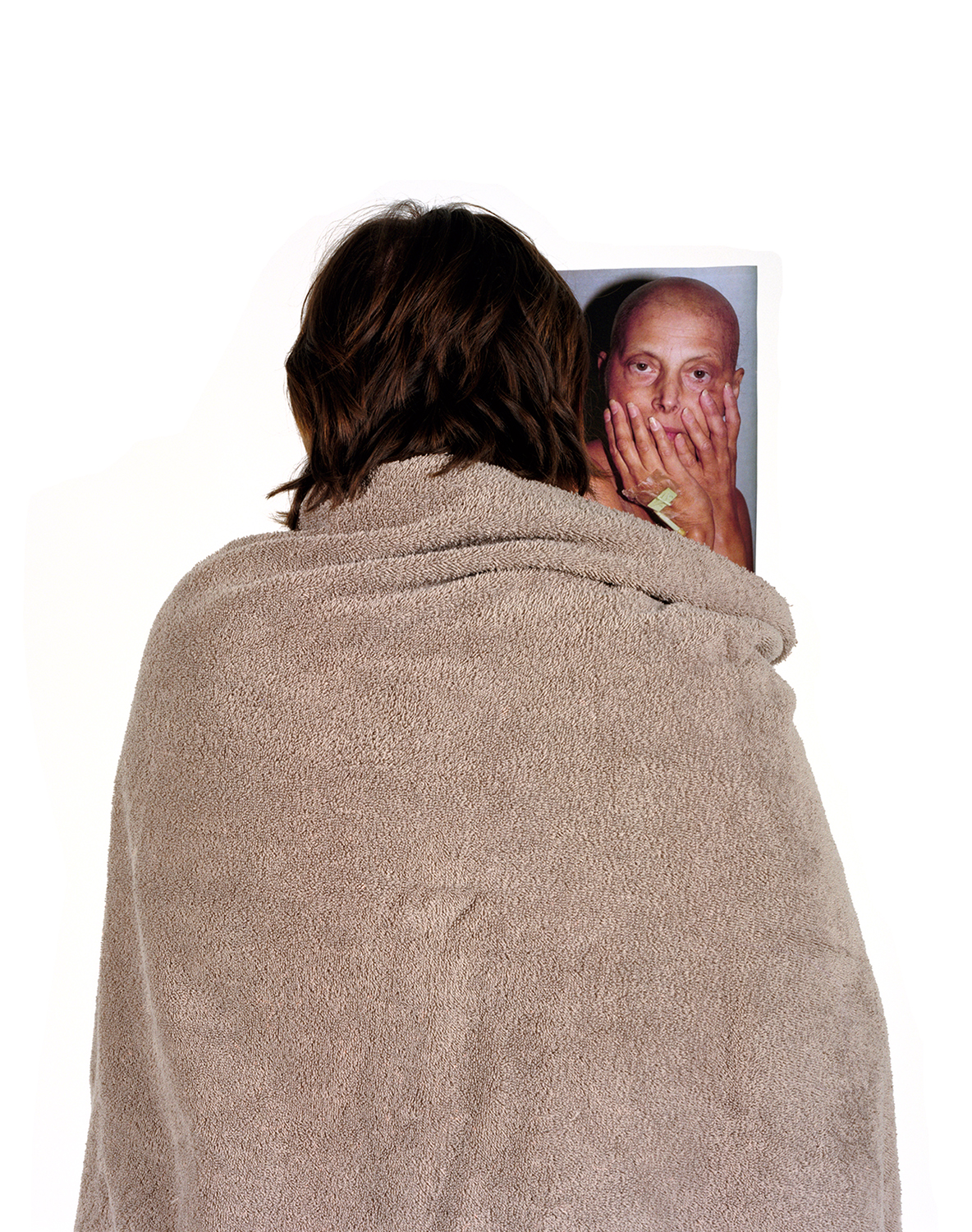

"Sitting with Ross in L.A," from the series (Not) Knowing Felix

AH: In "Having Been There," you interrupt the photographic frame and make obvious the materiality of the photograph. It also seems important that it is your body that interacts with the work. Tell me a little bit more about this and about how the process of creating images such as, "With Ana Mendieta,” becomes a meditation on death.

KT: I am often frustrated with the flatness of photographs. In Having Been There, I wanted to break that flat plane. It is important that it’s my body in the pictures because that work is very much about my personal connection to those artists and to specific pieces of theirs. In With Ana Mendieta, I was looking at work she made while she was in graduate school in Iowa. I lingered on a performance she did called On Giving Life where she laid on top of a skeleton in a grassy field and breathed into its mouth. It was a performance where life and death came together. I made a life-size print of a photo from that performance and then cut out the skeleton so that I could insert myself in its place, imagining this deceased artist breathing life into me. I was also thinking about the tragic circumstances of Ana Mendieta’s death and those elements dictated certain formal aspects of the photographs (the top-down perspective and staging it on the concrete floor of my studio). In most of the photographs from that series I let the work being referenced and biographical information that I found in my research shape how I interacted with the artists’ imagery.

"With Ana Mendieta” From the series Having Been There

AH: That impulse makes sense and some of the work appears performative but the performance aspect is a component of the process rather than the end result. It’s important for me that the final piece is a still photograph. It seems like this is something that you are thinking about as well?

KT: Yes—they felt performative to me as I made them because of the staging and the physical interactions I had. In the end, I wanted them to be still photographs because it seemed that a photograph could hint at larger ideas of remembrance, intimacy, and futility rather than a specific set of circumstances or a narrative that might be communicated through the duration of a live performance.

AH: What about your relationship to photography and sculpture? How have they come together in your work?

KT: I was mostly making sculptures and installations before I went to graduate school. I tended to use materials that were ephemeral so that the works would degrade or disappear over time. Now that I primarily make photographs, I tend to do so in a very tactile way--either building props or sets that are sculptural or engaging in processes that involve my hand. I also think of the final photographs as objects, paying particular attention to framing or mounting choices and decisions of scale when thinking about how a viewer might move around an exhibition. Certain works, like Still Beneath the Surface, combine photography and sculptural elements within an installation.

AH: The work Still Beneath the Surface seems like a pivotal point between your older and newer work. Can you talk about what changed after making that work? What ideas became more concrete and how did it inspire a broader engagement with mourning and loss?

KT: This was an important shift for me. My mother passed away while I was in graduate school, but it wasn’t until five years later that I felt like I could address her death overtly in a project. I was fortunate to have an exhibition at a great space in Los Angeles called commonwealth & council, and the gallerist allowed me to do a site-specific project that altered the gallery. It was a project that was about the death of my mother, but I looked at that through the lens of Victorian mourning traditions. The Victorian era interested me because it seemed simultaneously repressive and emotive. There were all of these rules and etiquette around mourning and how, through clothing and behavior, you could signal to the public that you had lost someone.

The show consisted primarily of a room where I built a raised, pine wood floor and a photograph that hung just outside of the room. From the doorway, it seemed like there was nothing inside. It wasn’t until you stepped up into the room that you could see a small hole in the floor where you could view a photograph that had been buried underneath it. It is a photograph of me, made in the style of a Victorian-era post-mortem photo. In the image, there are printed photographs of eyes laying over mine. These were my mother’s eyes--taken from the last photograph I made of her before she died. This piece was a bridge of sorts—using some similar material tactics from Having Been There, but ultimately making the work more sculptural, more immersive. It was a way of using the space to speak to ideas of grief and the way in which grief lingers, always there under the surface. When the show ended, I capped the hole in the floor with the photo still buried there.

After making that work, I realized that I was done with looking at death through the highly specific associations or histories of well-known artists or family members. I wanted to zoom out and think more expansively about death and mourning. That led to the more recent work and looking at the way death is represented in the news media.

Installation view of Still Beneath the Surface

Custom-built pine floor, buried archival inkjet print, light

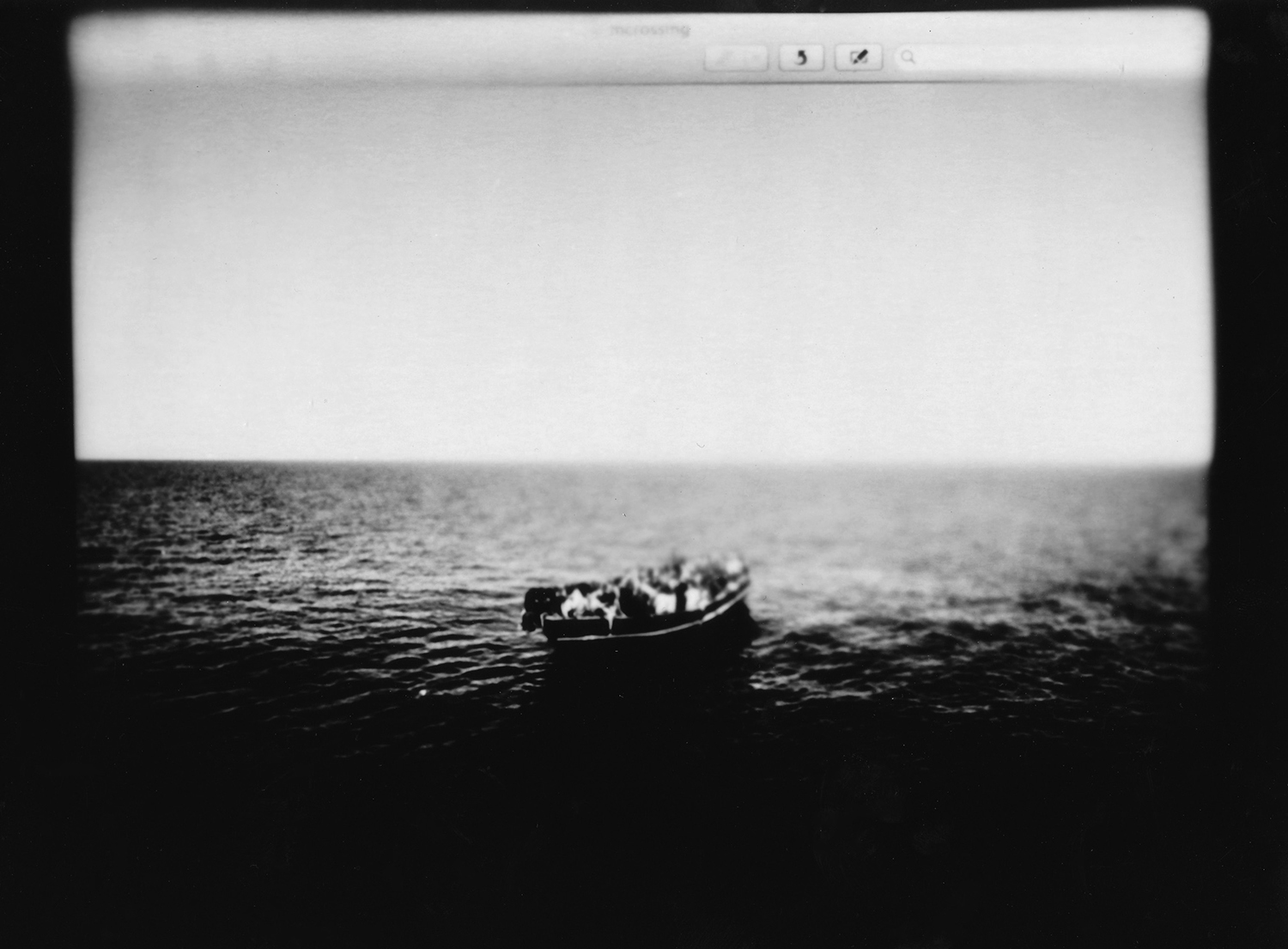

AH: Tell me about your recent body of work: Images Seen To Images Felt. What kinds of questions are you asking and how does the process of creating the work engage those ideas?

KT: This is a project that started because I often teach darkroom-based photo classes. In the breaks while waiting for prints to fix or film to process, students are constantly on their phones. It’s amazing to watch how quickly they consume information. I am also always reminding them to not bring their phones into the film processing rooms or the darkroom for fear of exposing their paper. At some point while issuing that warning, I wondered what that might look like and whether the light from a digital device could be used in a productive way to make a photograph. I had also been collecting images from online newspapers for years. I had a folder on my computer desktop of images from various news sources that moved me on an emotional level. I had no specific plan for using those pictures; I just felt the need to archive them.

Ultimately, I brought my laptop into the darkroom, opened one of those photos that I saved, and I pressed my black and white photo paper up to the screen. I was amazed by the result. The light from the screen burned a direct impression of that image onto the paper. I loved the fact that the process happened in a very tactile way; I am touching the individuals or scenes, and my touch translates or transforms that original photo. The process of making them slows me down. It’s my hope that by taking an image that we typically encounter on a digital device and turning it into something tangible, it might also slow a viewer down.

In a media-saturated culture, what does it take for a photograph to move us? What does it take for us to linger on a photo in order to process or understand the difficult things depicted? These are the questions at the heart of the project.

Images Seen to Images Felt, installation view

Gelatin silver print photograms, exposed by the light of a laptop screen

AH: I find the process to be so powerful and suggestive in this work. Is the series complete?

KT: I want it to be a living, ever-changing piece, so I imagine it’s a series that I’ll continue to work on for quite some time. It’s important to me that whenever I show the installation that it contains some photograms that have been made very recently, alongside those made over the past couple of years. It allows me to put images and events in conversation with each other that would never otherwise be seen together.

AH: What artists, books, or podcasts are inspiring you right now?

KT: I am always inspired by Dario Robleto and his poetic combinations and transformations of materials. I’ve also been revisiting the work of Berlinde de Bruyckere, Doris Salcedo, and Marlene Dumas. All of them deal with mourning in compelling ways.

My first photo teacher, Pamela Bannos, has written an amazing book called Vivian Maier: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife that I’m digging into. I’m also enjoying Mark Alice Durant’s book 27 Contexts.

I’m a big fan of the podcasts Criminal and This is Love. There’s also an episode of RadioLab called To See or Not to See that I listen to several times a year. It raises questions about what right we might have to witness the end of people’s lives. I can’t recommend that episode highly enough (though have some tissues handy)!

AH: What’s next for you? Any big plans for the summer?

KT: I have a couple of solo exhibitions scheduled for the fall, including one at Antenna Gallery in New Orleans that I’m very excited about. I’m looking forward to concentrated studio time this summer to make the work for those shows. I also hope to take a road trip back to Los Angeles to see friends and continue work on a long-term project there about people who die with no next of kin, the L.A. County Cemetery where those individuals are buried, and the city workers who intervene as caretakers in that process.

AH: Thank you so much for sharing your work Kristine!