Q&A: Kristine Potter

By Rafael Soldi | November 8, 2018

Kristine Potter received a BFA and BA from The University of Georgia and an MFA from the Yale School of Art in 2005. Her work has shown nationally and internationally including at such galleries and institutions as Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York City, Equinom Gallery in San Francisco, Light Work in Syracuse NY, The Georgia Museum of Art, The Neuberger Museum of Art, 601 Artspace, and The Girls’ Club Foundation. Her work belongs in numerous public and private collections, including that of The Georgia Museum of Art, Light Work, and 601 Artspace. Potter was selected as Artist in Residence at Light Work in 2014, and her work has been recognized with nominations to the MACK First Book Award, as well as the Shortlist to the 2016 Kassel Book Prize. She is a 2018 Guggenheim Fellow.

Potter has held numerous faculty positions at such institutions as: School of Visual Arts, Hunter College, and the State University of New York Purchase College. She is currently teaching at Vanderbilt University and Watkins College of Art and Design in Nashville, TN.

Potter’s work has been published in Contact Sheet (no. 182 and no. 190), Paper Journal, and by Roman Nvmerals Press. Her first monograph, “Manifest” was published by TBW Books in 2018, and reviewed on Strange Fire Collective by Jess T. Dugan here.

Rafael Soldi: Hi Kristine, thanks for chatting with us.

KP: Hi Rafael, thanks for having me.

RS: Let’s jump right in. What's your background? How does it manifest in your work, and what led you to photography?

KP: I grew up as a military brat with a few uncommon traits. Typically military kids move around every couple of years, but when I was 4 or 5, my family settled in Central Georgia adjacent to the military base, which employed my father. I come from a multi-generation Army family, so we are deeply culturally military. That is something that is a little difficult to explain because it is not rooted in geography or typical cultural expressions like food or music. (It’s not uncommon to hear a prayer for our troops at Thanksgiving dinner, for example.) The culture is rooted in patriarchy and patriotism, with a sense of duty outweighing most else.

I’m naturally suspicious of ideologies and un-questioned traditions, so I took to challenging the world-view of that little military town as early as I can recall having an opinion. I made my way through high school by listening to as much music and watching as many movies as I could - it felt like those were the only cultural imports in the whole town. My goal was to move to New York City to immerse myself in the arts.

Photography came to me in a serious way in college at the University of Georgia. I was studying Art History at the time and needed to take a few studio classes for my degree. I thought photography sounded cool and I ended up in a Photo I class with Mark Steinmetz. The rest is really history. He opened up this whole beautiful and mysterious language for me and I never turned back.

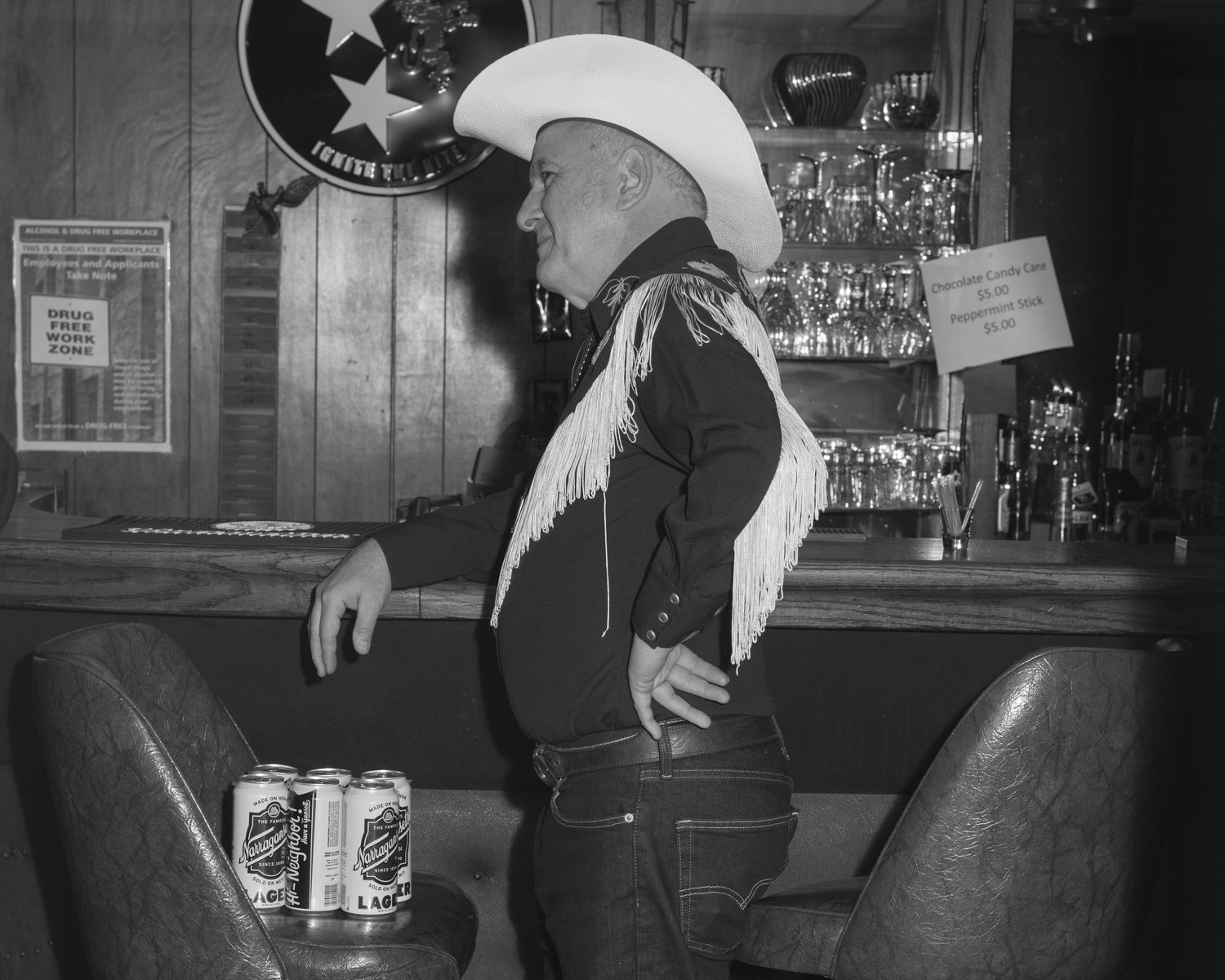

From The Gray Line

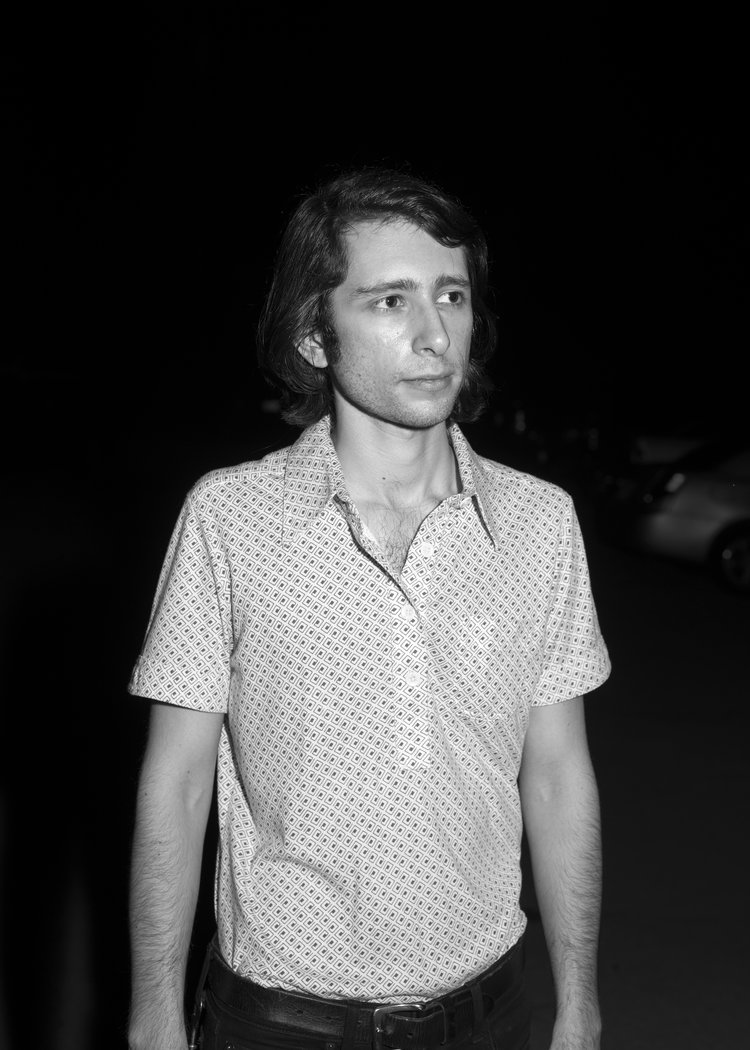

RS: You mentioned to me once that your subjects in The Gray Line are "in-between" in every way. What do you mean by that? Can you tell us a little more about the project? I'm also curious about your choice to include archived images from Vietnam.

KP: The Gray Line portraits are of male cadets at West Point at the height of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. On top of feeling as though the wars were misguided, the binary language of the time was off-putting to me, right or wrong, enemy or ally, with us or against us, etc…

I felt like one way to address the gray area that exists was to look at young men who were in an extended state of becoming. West Point is a four-year military college where cadets enter as civilians and leave as ranked officers. Those four years are not just an academic pursuit; they’re filled with mental and physical conditioning. I hope the pictures show a weight and counter-weight. I hope they show humanity, vulnerability, pride, honor, fear, hopefulness, sensuality, and a spectrum of other emotional expressions.

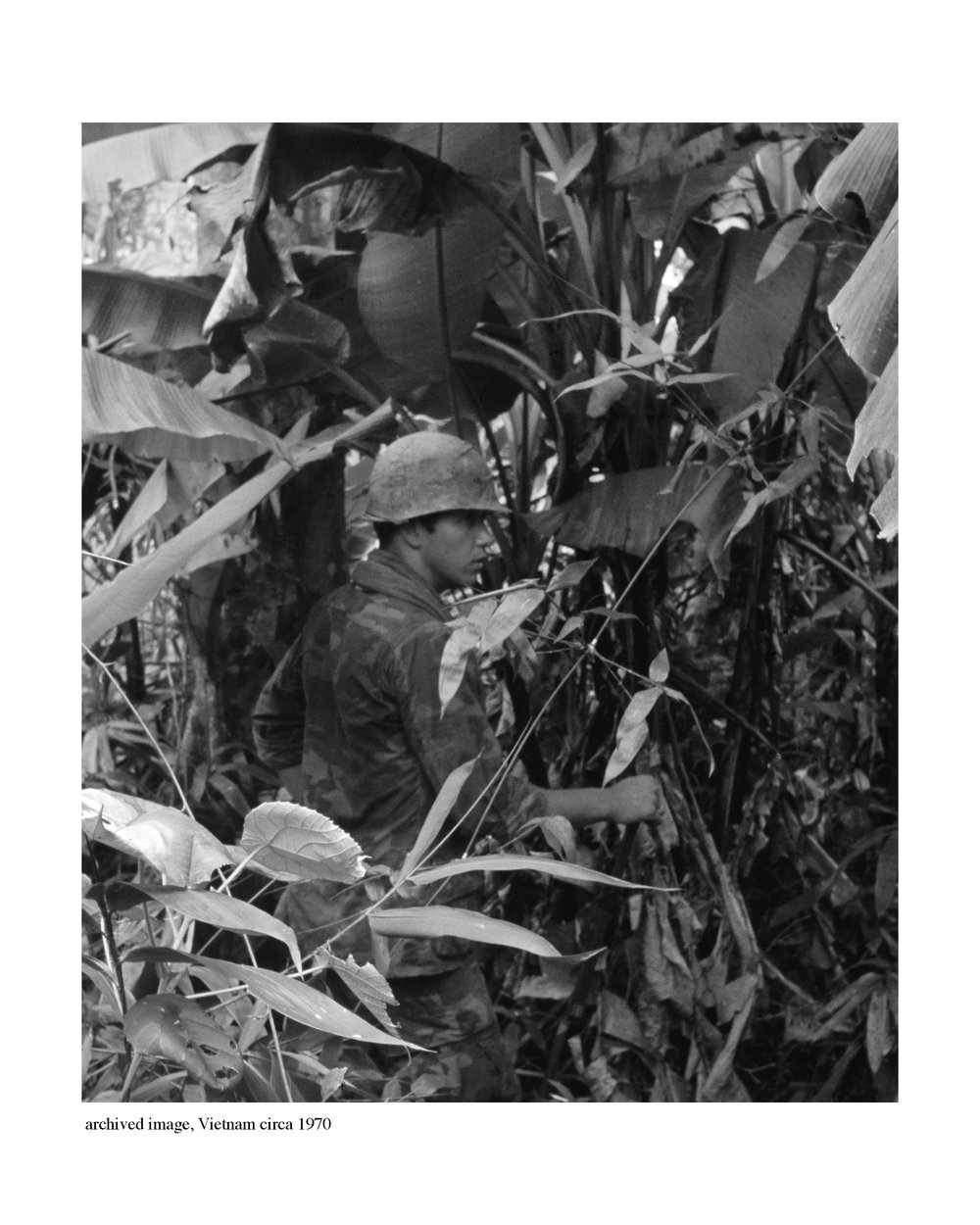

The archived images my father took in Vietnam came many years later, when I exhibited the work at Light Work in Syracuse, NY. The work had incurred a little Internet fame and controversy and I was quite happy to just put them away for a good while. When Light Work asked to show them, I wavered but thought, okay… if I am going to bring this work back out, I’m going to make it monumental. So I made a limited XL edition of the prints and I interspersed some enlarged photographs my father took in Vietnam. Part of the controversy surrounding my work was that I had feminized these young men by viewing them in repose, or at rest. I won’t digress into all the ways this argument is problematic, but I will say that the pictures from Vietnam were one of my answers to that criticism.

RS: When making portraits how much attention are you paying to gesture? Would you say gesture is a paramount element of your portrait-making?

KP: Gesture and expression are my two main concerns when making portraits. I try to stay as observant and responsive as possible when photographing someone. I study a lot of figurative painting, I watch how people move, and I’m deeply interested in how slight changes in facial expressions can read so differently when frozen in a photograph.

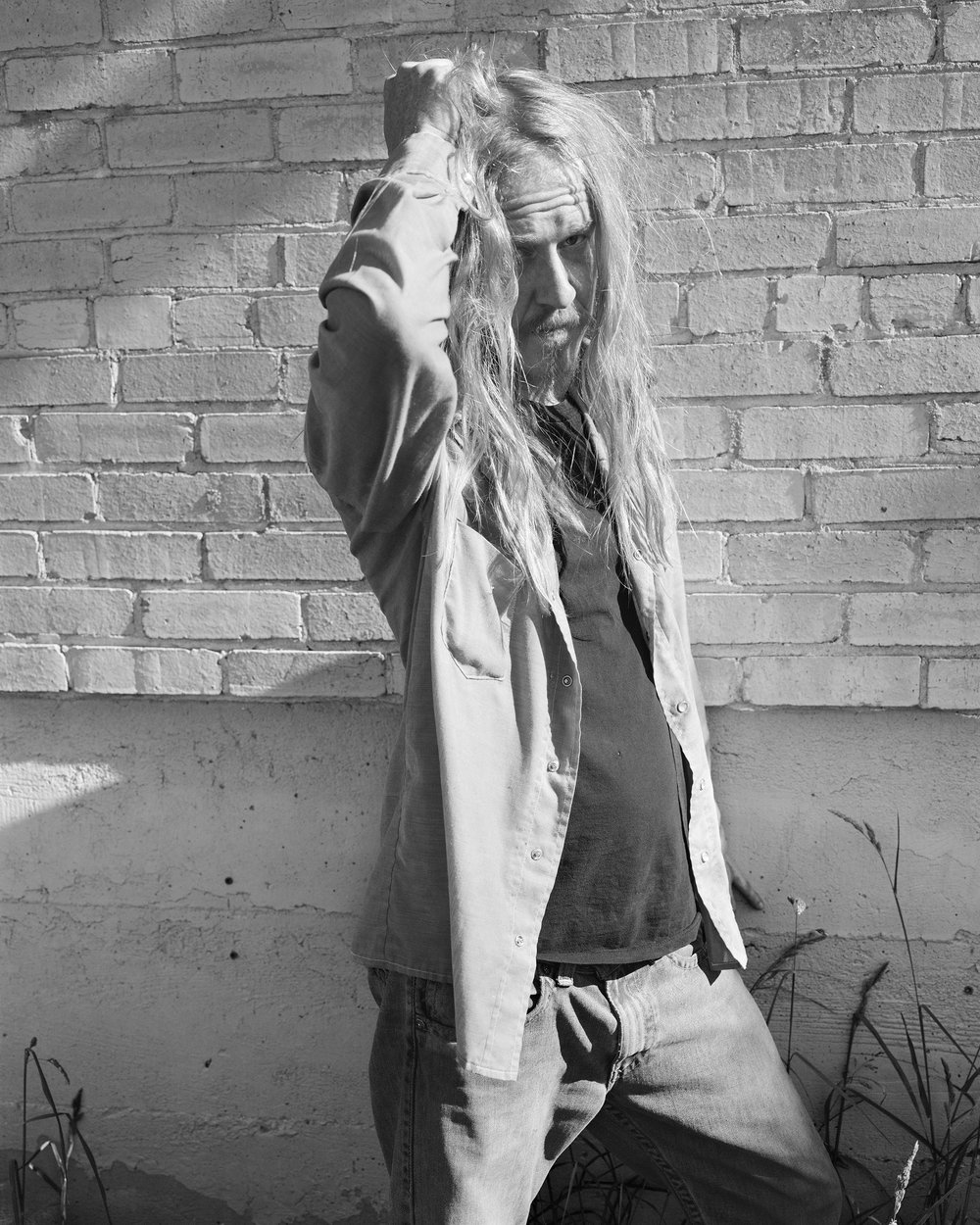

From The Gray Line

RS: West Point was so regimented, so the wild American West must have felt like such a shift. What attracted you to turn your lens to such a charged territory? What's Manifest about?

KP: West Point was important work for me, but once it felt complete, I was ready for a dramatic shift. Manifest was borne of a few coinciding interests and discoveries, and it really took shape over a couple of visits out west. At the outset, I wanted to photograph another archetype of American masculinity, the cowboy. But it was more than that… I had been helping my family sort and archive some ephemera we inherited from my great-great grandparents who were sharpshooters at the turn of the 20th century. They toured with Buffalo Bill and others, and the newspaper clippings from the 1890s extolled all of the incredible grandeur and drama of the American West. They, and others like them, were some of the first purveyors of the mythology we now know about the region. I was interested in that familial connection as much as I was interested in the story we have told ourselves about who we are and how this land was settled. Mix all of that with a rather traditional impulse to head west to make photographs, and I had a new direction for myself.

[Note: See Strange Fire’s review of Kristine Potter’s book, Manifest, here]

RS: For you it's not just about the landscape, but those who inhabit this inhospitable land—the American Cowboy and the myth surrounding it. There is a long history of monumental men charting the landscape with their large format cameras—a real boys club that persists today still. You turn your lens to the men who occupy this landscape, and these men are not heroic or mighty, they're rather fragile. Whether you intend it or not, I read this as a flipping of the power structure—a unique reading on this terrain that could only come from a critical female gaze. You've mentioned the work is not specifically about masculinity—what is it about, as it relates to the images of men in the landscape?

KP: Any student of photography learns about the big names in western survey photography, Carlton Watkins and Timothy O’Sullivan, just to name two. But there are many that took on the hard work of mapping the acquired territory and reporting back what was there for the country’s taking. I love those photographs. They’re extraordinary and I’m in awe of what it took to make them. But when I really got out there for a substantial amount of time, I found the landscape to be so much more disorienting and inhospitable than those pictures let me see. I came to see those survey photos as these kind of vista view repositories for our dreams and aspirations. And of course that region is still quite remote, because the truth is, it isn’t very easy to maneuver. That observation and experience led me to see the land and the men who inhabit it in a very different light than I think it has been seen before.

I’m always interested in flipping power dynamics, and that of course applies to what I see as a historically masculine interpretation of the region. In a lot of ways, I like to see the landscapes as the feminine energy in the work. In other ways, I see it as my lens. Either way (and maybe it is both) the men are not asserting control.

RS: I love my copy of the Manifest book. It is so beautifully edited and crafted!

KP: Thank You!! I’m really so happy with it. Working with Paul Schiek and Lester Rosso at TBW Books was such a pleasure and we are all super proud of this book.

RS: I wasn't aware of this phenomenon of bodies of water with violent names. Dark Waters is a timely and poignant developing project for you. Tell us more about how these images, which speak to the violence of settling the landscape, among other things, reflect our current times. What strategies are you using to create contrasting images throughout this body of work?

KP: I hesitate to say too definitively what I’m doing with the work, as it is still very much in progress. I’ll say that violence and the landscape were on my mind out West… just how much violence it took to acquire this land and how often those details are glossed over in the stories we tell ourselves about who we are. The real generative impulse in the work came from a creek I used to cross all the time growing up in Georgia; Murder Creek. I used to create all kinds of stories about who lived on the creek, how it got its name, and what it means have that name attributed to the landscape. I started researching for similarly named bodies of water and found there to be quite a lot in the southeast.

Simultaneously, I was becoming aware of, and fascinated by, the history of murder ballads in the American Songbook. These songs belong to folk and bluegrass traditions, but have been performed and reinterpreted exhaustively since the colonies took shape. As the title suggests, the songs detail murders. Not all, but many of them detail the murder of a woman at the hands of a jealous man, and more often than not, her body is submerged in a river. Ironically, they are catchy upbeat tunes. It’s almost easy to miss how morose they are. I suppose we’ve always been receptive to violence against women as entertainment.

So these are the two main ingredients in the work. I’m traveling around making waterscapes (as I call them) and photographing people who are around the water. I’m also making some studio portraits about the women in these songs… reviving them of sorts. I’m also working on some video and sound pieces… but those are really unresolved at the moment. So who knows what it will all add up to in the end... or if I could explain to you my strategies for image making… I’m still in the stage where I’m trying different things to see what works.

I will agree that it feels timely, but not in a direct way. I’m going to deal with our darkness in a metaphorical way.

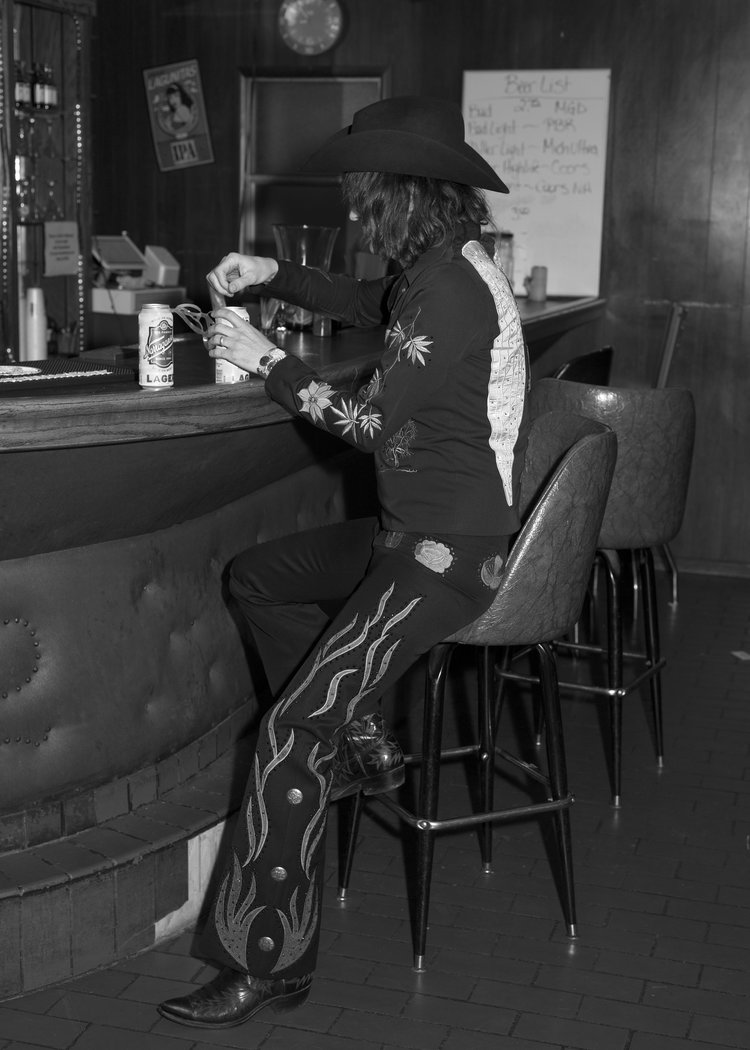

RS: I’m looking forward to seeing this develop. In many ways your project Nashville Nights stands out from the rest of your work. There's a candid, more unstructured rhythm to it, as well as a sense of humor. Is this true of the making of it too?

KP: Nashville Nights started very casually. My husband is a pedal steel player and so when we moved from NYC to Nashville, we were going out a lot to check out the music scene. We still go out often. Like New York, there is the tourist version of Nashville, and then there is the real deal. It goes without saying that this town is musical. I mean, you can walk into a hole-in-the-wall bar and see virtuosic musicianship while sipping a $2 beer. It’s incredible. But what surprised me most was how fantastically theatrical the people can be. I was transported immediately to the black and white bar pictures that Eggleston used to make in the late 70s down in Memphis. I thought… I’m just going to start bringing a digital 35mm and flash with me. It doesn't hold the same conceptual weight as some of my other projects, but I'm perfectly fine with that. It’s fun, I don’t think too much about it, and I get to meet people.

RS: What's next for you?

KP: Well, I think Dark Waters is going to hold my interest for a couple of years. It feels like it is really just beginning. But otherwise, who knows?? I’m open, I’m looking, and I’ll respond when compelled.

RS: We look forward to following along!

KP: Thanks so much for the questions! It's been a pleasure to talk with you about my work.

All images © Kristine Potter