Q&A: erina alejo

By InHae Yap | January 28, 2021

Erina Alejo (they/she) is an artist, researcher, and educator. They recently published A Hxstory of Renting (2020) and are completing My Ancestors Followed Me Here, commissioned by SFMOMA. Alejo builds visual and temporal archives on displacement and community history from their lens as a third-generation renter in San Francisco—the unceded ancestral homeland of the Ramaytush Ohlone. Alejo works for the Office of the Vice President for the Arts at Stanford University, and organizes with their home community, San Francisco’s SOMA Pilipinas Filipino Cultural District, on programs like SoMapagmahal, a Filipinx and Ethnic Studies photography mentorship program that equips youth of color to use photography as a tool to examine the ongoing impact of urbanization. Alejo studied Visual Arts Media, Human Development, and African Studies at the University of California, San Diego.

They are the recipient of Center for Cultural Innovation, San Francisco Arts Commission, Southern Exposure, Asian Pacific Islander Cultural Center grants, and Balay Kreative’s Inaugural Grantee. Alejo has presented their work at the Asian Art Museum (San Francisco, CA), Stanford University, Free Minds Free People (Baltimore, MD), Association for Asian American Studies (San Francisco, CA), California State University Long Beach, and Filipino American National Historical Society (Chicago, IL).

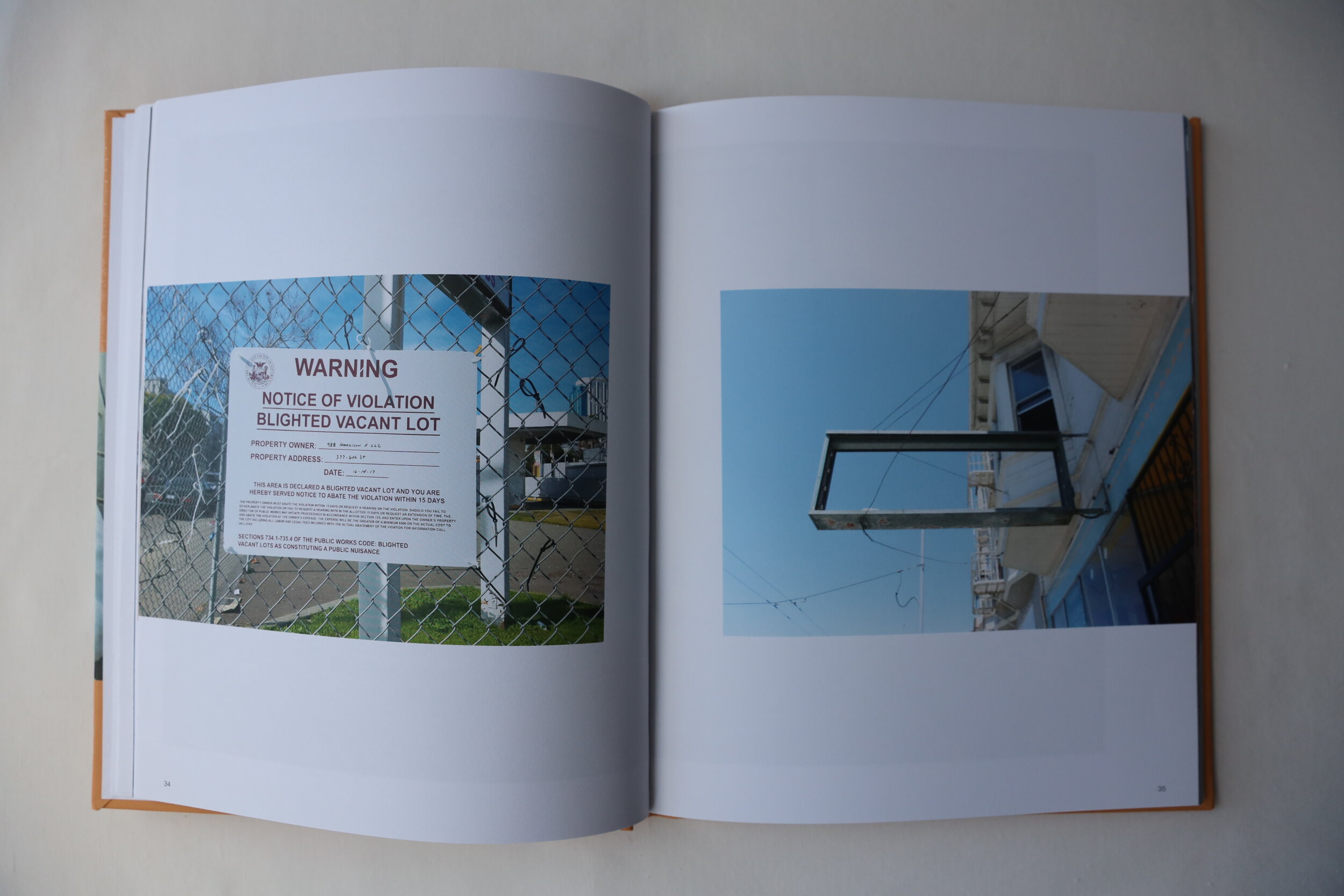

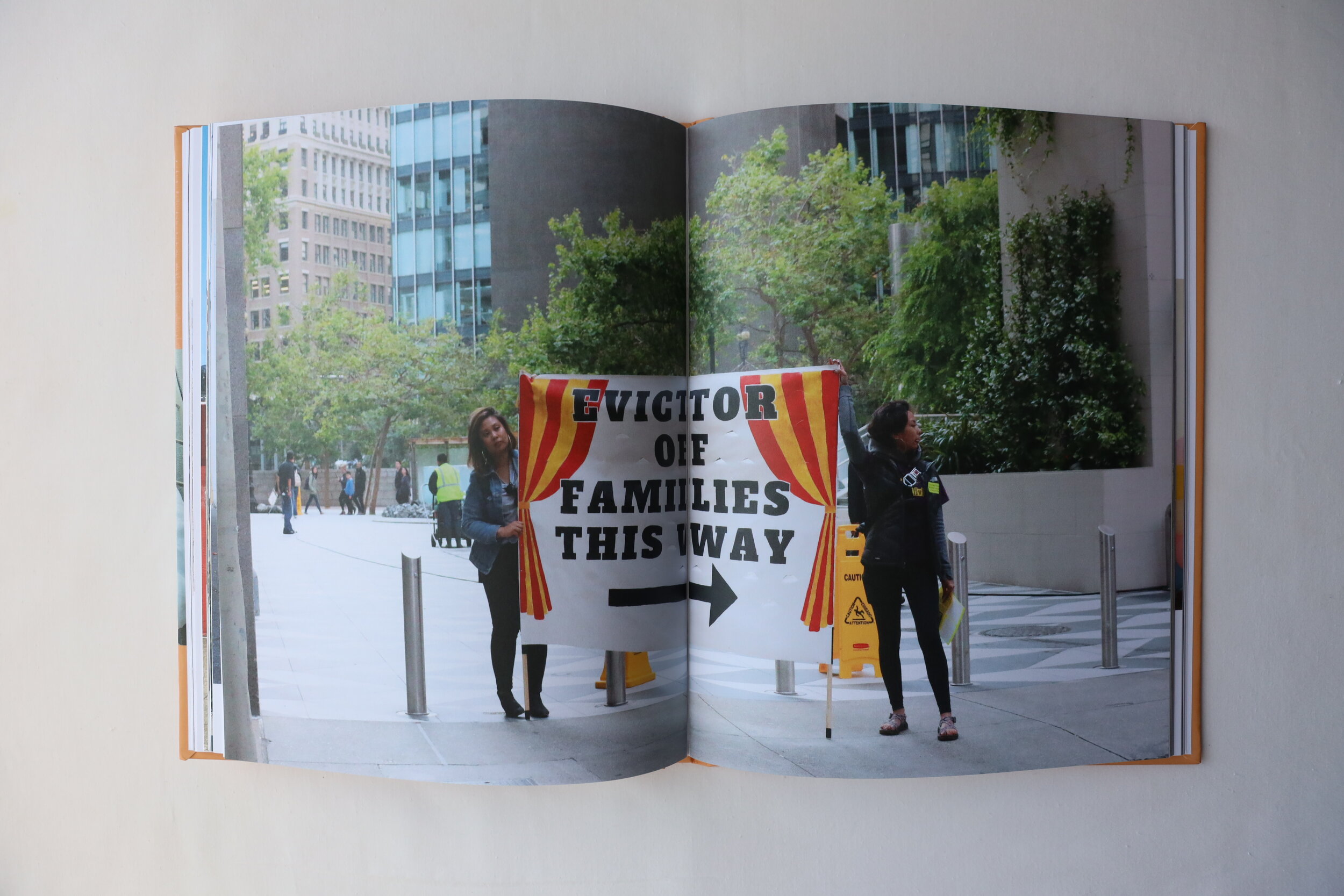

The Perez Family's Illegal Eviction, 2020. Courtesy of artist.

InHae Yap: You describe yourself as a “third-generational San Francisco renter,” and much of your work investigates the implications of that identity, for yourself and others. For folks who might be less familiar with the Bay Area’s so-called ‘housing crisis,’ I’d like to start by asking about your personal experience growing up in the Bay Area as a third-generation renter, and what led you to explore this identity through artistic practice.

Erina Alejo: My family’s renting status began in 1959 through my grandaunt, Lola Marina Peña (1922 - ). She moved with her children and late husband from our ancestral property in Nueva Ecija, Philippines, to rent a two-bedroom apartment in the Pittsburg Marina, California. Lola Marina eventually purchased and owned property in Pittsburg, while my immediate family (grandparents and mom) moved to San Francisco to rent, which is still our present reality. Instead of asking why we ended up as renters after 60 years of living in the Bay Area, I wanted to understand how our family situation is a related experience for other families, especially for working- and middle-class families, considering we are in the present and perpetual global housing affordability crisis. I want to also understand what the future holds for current renters, my generation, and future ones.

Projects like UC Berkley’s Urban Displacement Project, and the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project teach me more about the expansive history of renting, and where to locate my intervention as a storyteller. I also reflect upon systems of economic governance and private property like feudalism and having landlords. When we think about it, these capitalistic systems are still relatively young, just a few centuries old—yet they have driven the fate of many lands and peoples, like my family’s homeland, now called the Philippines, and the Filipinx diaspora. I think about how these systems of privatized, non-communal social control manifested in Spain’s encomienda system across the Americas, the Philippines, among other lands, which abused and enslaved indigenous peoples. The idea of renting as a practice holds a broad and complex history—I’m forever learning and making connections: its proximity to whiteness, white supremacy, and futurities in decolonized methodologies.

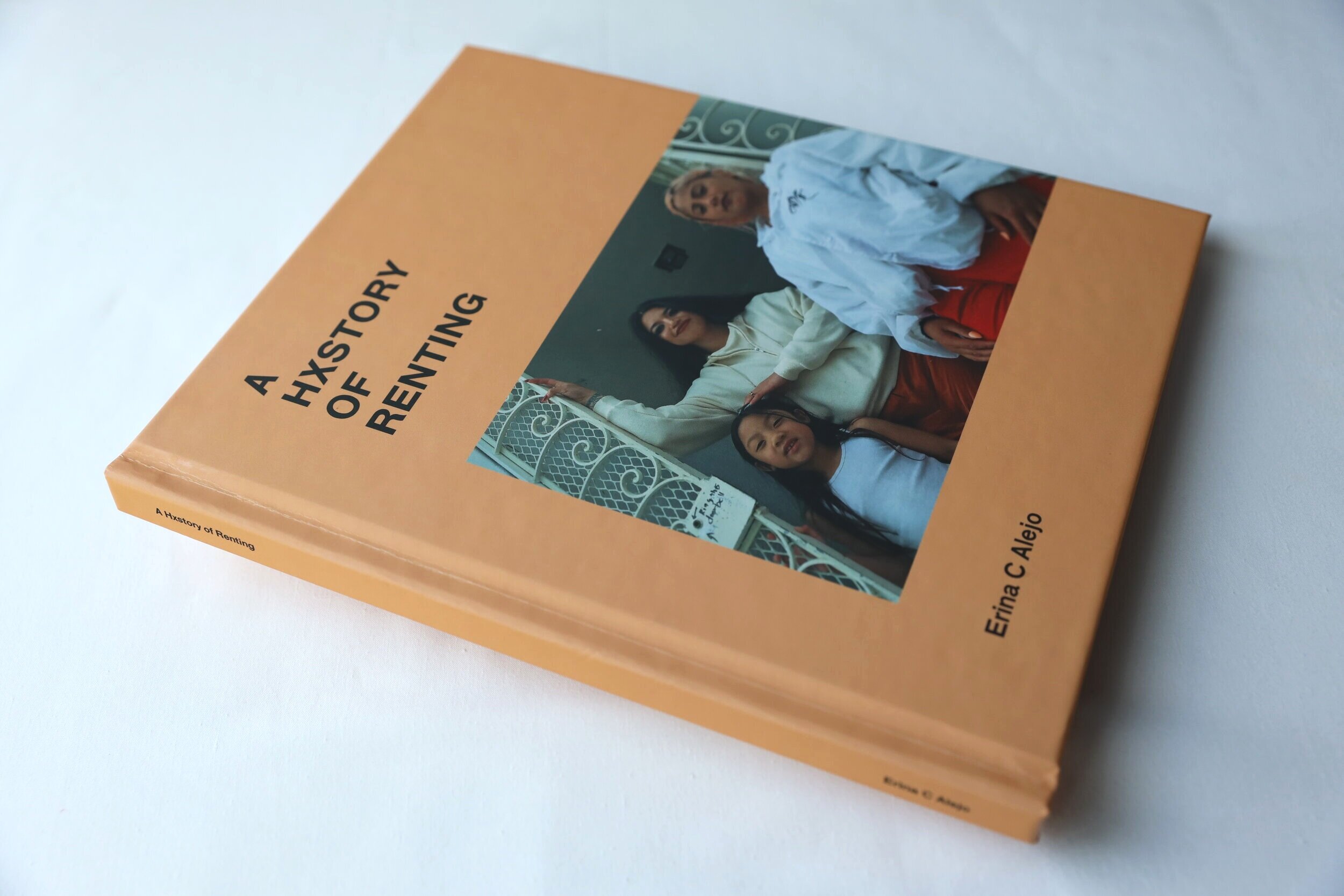

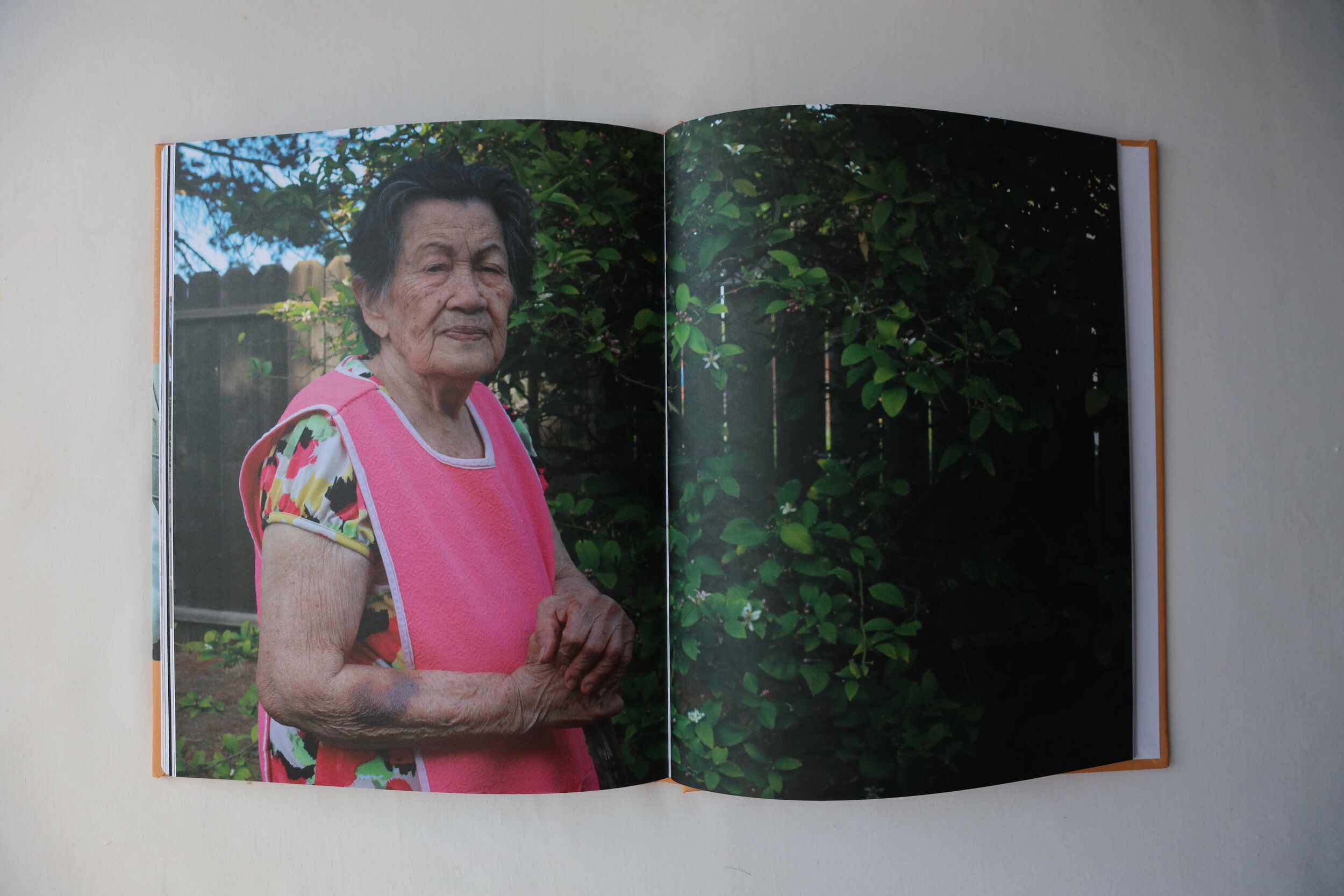

A Hxstory of Renting (2020). Courtesy of artist.

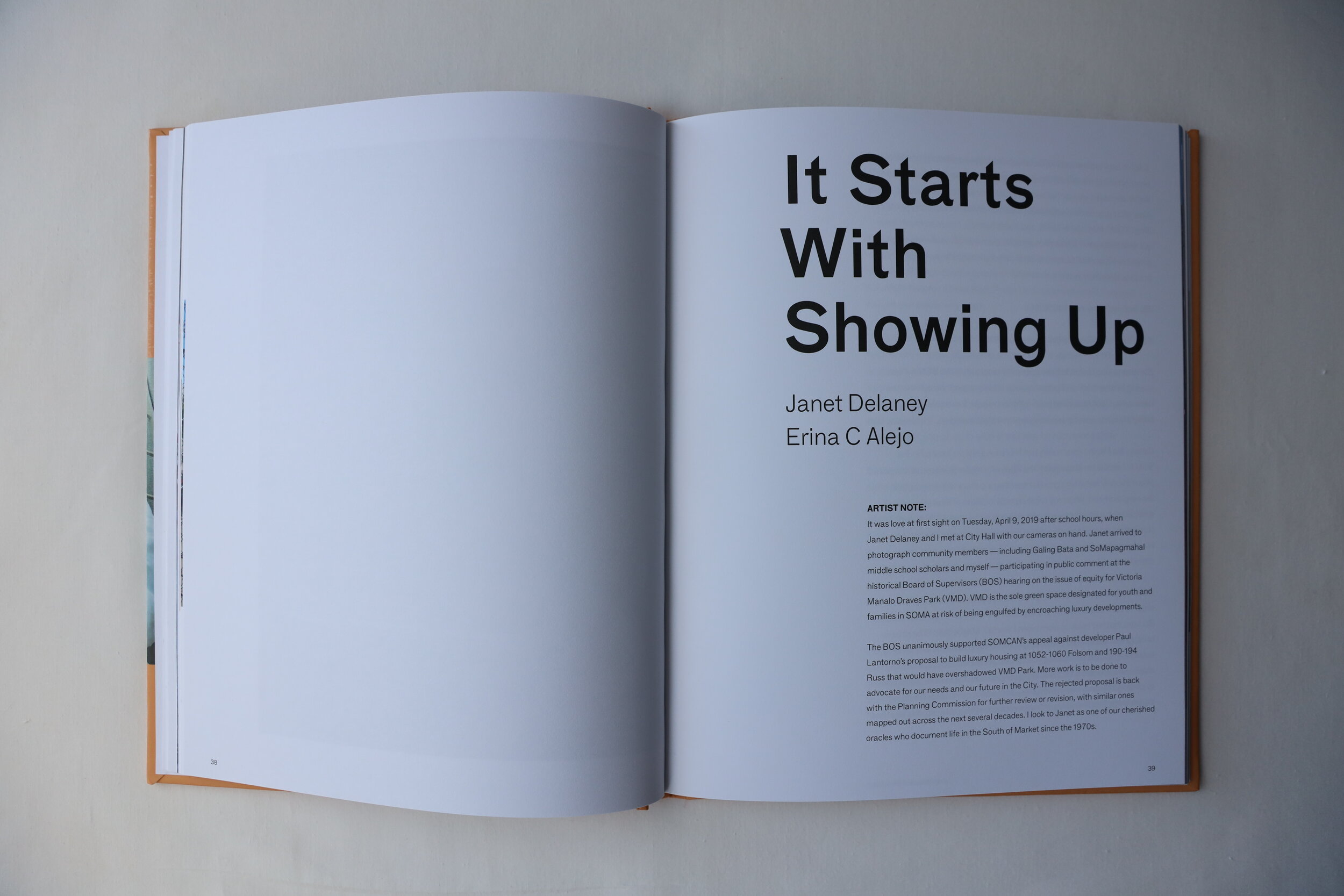

IY: Let’s talk about your book, A Hxstory of Renting (AHOR), which you describe as “a multi-platform project spanning decades and geographies … [examining] the visual culture of gentrification, displacement, and resilience of San Francisco/Yelamu.” How did this project first come about?

EA: The passing of three of my elders within a ten-month period, signified to me cultural change, and created the foundations for AHOR: Conchita Alejo, my grandaunt and matriarch whose home in Southern California historically functioned as a halfway house for many of my recently immigrated relatives before they carved their own legacies in a new country; my aunt and former neighbor, Zenaida Perez, whose posthumous eviction from her San Francisco apartment opens the book; and my Lolo (grandfather) Jesus Urrutia, whom I lived with until his passing.

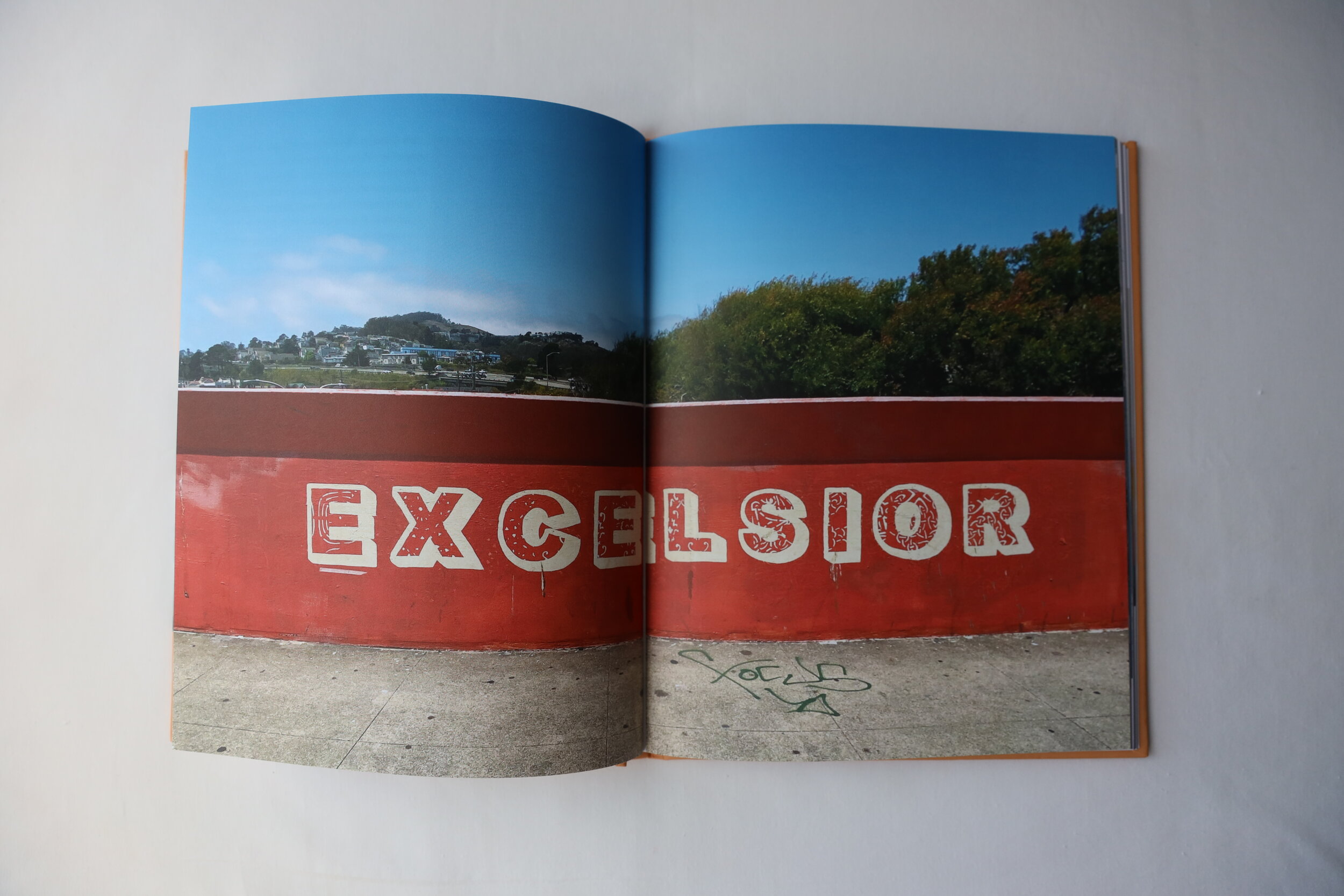

I was entrusted by loved ones to either photograph these late elders’ funeral service, their eviction process, or their gradual health decline. During this period, I also sought refuge in photographing things in the periphery: adjacent objects, landscapes, and community gatherings. In the process, I noticed my accumulated photos of 2000s-era television sets which I found discarded along my neighborhood sidewalks—a sobering timestamp of possessions previously belonging to families who had moved to my neighborhood, Excelsior, during the dot-com bubble burst, only to be relinquished as these families departed the district, or city as a whole, 15-20 years later. I connected these abandoned belongings to my elders’ passing, especially my Lolo Jesus’s, who represents a disappearing Excelsior, one of the last bastions of San Francisco neighborhoods for working- and middle-class families.

The precursor to AHOR are several unpublished photo books, including Please Close Gently, which, out of frame, documented the events of these three elders’ passing through objects, spaces, and feelings. An excerpt is featured on Bomb Cyclone’s first issue.

IY: What I found interesting in AHOR was that it doesn’t single out Silicon Valley as the primary perpetrator of Bay Area gentrification–though the tech boom was, of course, a significant factor. Instead, it locates the beginnings of corporate incursions into San Francisco in the postwar era (David Woo’s essay in particular). This idea of longer, deeper histories imbues AHOR, which is dated (1959–), coinciding with your grand-aunt’s arrival in this country. In that sense, too, the project does not end with you, but connects also to future generations. Can you talk about this interweaving of collective memory and individual experience? What’s the significance of this gesture, either as archival intervention or invention?

EA: As you so generously cited, contributor David Woo’s introductory essay, “A Future That Puts People First”, traces a post-war period in San Francisco history when private interests, with the government’s backing, eyed lucrative advancements through urban renewal projects to develop the city as the economic and financial headquarters of the Western Pacific Rim. In the process, BIPOC, immigrant, working and middle-class communities were de-prioritized and displaced, particularly in neighborhoods that remain to be ground-zero for the tech-fueled gentrification crisis, which AHOR focuses on: the Excelsior, Mission, and South of Market districts.

Yet, as observed by David, this city-wide corporate restructuring through high-rise office development and the building of the grid of freeways gave rise to the creation of ongoing neighborhood-based opposition movements, including by communities residing in these aforementioned districts. “Organizing is how we fight back,” David writes.

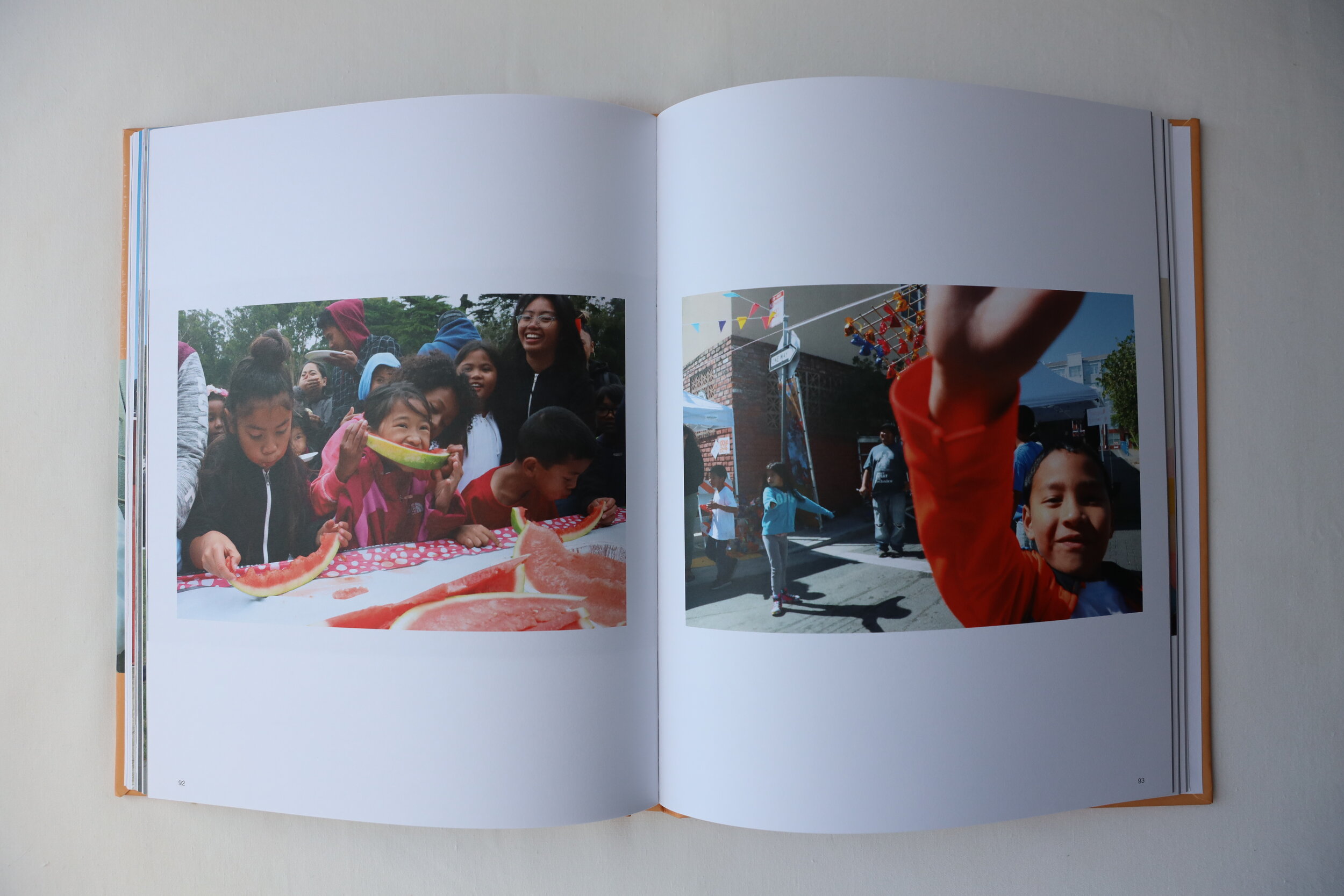

With that said, I think about the book’s method of archival intervention, of progressively decentering displacement and gentrification and instead focusing on community power and resilience through images of youth and families who live, breathe, eat, play, sing. They are the masses of people who embody the potentialities in neighborhood-based grassroots organizing—by engaging the tensions between collective action and individual identity, personal and communal space.

Excerpt from Please Close Gently, 2016. Courtesy of artist.

IY: Your work often feels like an intimate conversation between yourself and the organizers, working-class immigrants, and communities of color in SOMA, the Mission, and Excelsior. As an outsider, I can observe this dialogue, but these photographs and essays aren’t for me, exactly–yet I am still a participant, if a silent one. I’m wondering whether you had such ‘outsider’ viewers in mind while making this work, and if so, what you envision them walking away with.

EA: The book highlights a facet of the universal housing affordability crisis, gentrification and displacement through a case study of a stretch of San Francisco from my lens as a Filipino-American (Fil-Am) ethnographer who has been photographing my Filipino and Fil-Am community. I find it important to bring the Filipino experience to the discussion of housing affordability, gentrification and displacement because doing so enriches the dialogue. Filipinos are immigrants and settler colonizers to the US. Like many cultures and peoples who have come to the US, we come from a large global diaspora.

I see AHOR as relatable even to people beyond the those whose lived experiences are in the book. I’m thinking of what my colleague, sound engineer, and dear friend spoke about AHOR. While he is a South Side Chicagoan, he connected with the book, especially as a child of a builder who witnessed the creation, destruction, and restoration of people’s homes. He phrased it a lot better, but he spoke of the AHOR book as a structure itself: how it is its own residence, creaks in the floor, flights of stairs and latchkeys, its own stories, its own tenancies and sovereignties, its own immigrations and emigrations, its own dreaming rest and waking action, its own “was here” and “still here.” Isn’t that so, so, beautiful? I’m really touched by what folks have been sharing with me about their thoughts on the book.

IY: Speaking of structures and the ways we inhabit them, I also wanted to discuss “place” and “space,” whose conceptual relationship seems central to your work. In Plants Have Feelings, you use geospatial mapping and user submissions to create a unique narrative of San Francisco through human/plant interactions. Similarly, you’ve organized public installations and neighborhood tours as part of AHOR, calling attention to the spaces impacted by ongoing displacement and gentrification. The presence, or non-presence, of people and communities seems to be key in retaining San Francisco’s sense of “place,” even as its literal “space” is razed, built up, restructured. Can you elaborate on that?

EA: As someone whose media-making foundations began in filmmaking, I remain fascinated with the concept of the mise en scène (setting or surroundings of an event or action) and the b-roll (secondary footage). Studying documentary and ethnographic filmmaking cemented my interest in attuning to this negative space—what takes place out of the camera’s focus—and, to not speak for, but, simply “nearby”, as how scholar Trinh T. Minh–ha speaks of her participatory-observational ethnographic work.

Plants Have Feelings, a collaboration with Lian Ladia which gathers and maps plant histories, unearths a quiet, yet profound gesture of resistance through a 1970s inner-city garden located in the light well of San Francisco’s International Hotel on Kearny Street, tended to by the late activist and organizer Luisa “Mrs. D” De La Cruz. During the city’s period of Urban Renewal, the building, known as the I-Hotel, and its residents were at the front and center of an eviction process. Mrs. D. rarely spoke in rallies, but she made her mark in this contested public space and the activism prism of the I-Hotel struggle and the history of Filipinos in San Francisco through the garden which nurtured a sense of home for the seniors and long-term residents.

By citing Mrs. D’s light well garden in Plants Have Feelings, we show one quotidian evidence of existing placekeeping strategies to understand our community cultural wealth, futurity, and collective resilience in a place. AHOR uses this same method in its visual archives of cultural objects like my late aunt’s passport strewn on the floor, photographed during her posthumous eviction, seemingly mundane iconic landmarks like a neighborhood laundromat at golden hour, and community events like an anti-eviction protest or a youth watermelon eating contest.

Plants Have Feelings Map, illustration by England Hidalgo, 2020

L-R: Claudio Domingo, Anacleto Moniz and Luisa de la Cruz (R) tended a garden in the second-floor light well of the I-Hotel, circa 1970s. Photograph by Crystal K. Huie. Courtesy of the Huie Estate and Manilatown foundation.

IY: AHOR was recently published as a book by clamshell press, but the book represents only a small snapshot of AHOR’s larger community-based collaboration, which includes other art pieces, performances, and photo essays. Tell me about the process of curating AHOR for its material book form. How did you decide what to include or exclude?

EA: Leading up to the photo book form of AHOR, across five years, I have been experimenting with various media: installations, public interventions, neighborhood tours, performance works, and photo essays which revolve around the themes of care, cultural preservation, and community action. I see all these works as forms of fieldwork and data-gathering for what became AHOR as a photo book. [1]

In summer 2019, prior to clamshell press picking up this book project, everywhere I went, I carried around thick stack of 4x6 photos printed from Walgreens–around 500 photographs from my digital photo archive of tens of thousands. From this physical stack, I slowly narrowed down the photos, gathering input from community like photographer elder Tony Remington, who documented the I-Hotel residents and protests. I wore out copies of my mentor Brian Cross’s Ghost Notes: Music of the Unplayed, LaToya Ruby Frazier’s The Notion of Family, Jeremy Villaluz’s Enclave, and Janet Delaney’s South of Market—all influential photo books to developing AHOR. I set up informational interviews and discussed my project with community members and organizers in art, urban planning, public health, mental health, education—my family, too. I learned this interdisciplinary, tactile, and critique-based method of editing from courses at UC San Diego, and teaching middle school youth artists through SoMapagmahal Photography Mxntorship Program at my former workplace, Galing Bata Bilingual Program in San Francisco’s SOMA Pilipinas.

Backpacks of FEC Galing Bata students, 2016. Excerpt from A Hxstory of Renting, 2020. Courtesy of artist.

IY: One of the biggest ironies of doing artistic or research-based interventions into capitalist institutions is that we are frequently beholden to them, primarily for grants and other resources. Private universities, in particular, support such research while maintaining precarious, mutually wary relationships with their surrounding communities. Stanford, in particular, directly fuels Silicon Valley, and, by proxy of being the largest landowner in Santa Clara County, exacerbates housing issues in the area. You are involved in efforts both on- and off-campus to grapple with these issues, with ties to both “town” and “gown.” Can you talk more about this work? And how do you maneuver this relationship?

EA: Dang, InHae! This question is hard, brilliant, and hits home! I don’t think my answer can fully encompass your assessment of institutions like Stanford and its precarious mutualism with Santa Clara County and Silicon Valley, since I’m newly arrived to the community, but I will humbly speak from what I’m gathering so far.

In an unprecedented moment of collaborative possibilities, I am currently placed with levels of community responsibility in the San Francisco Bay Area—from helping author ideas of equity and structure for Stanford University’s arts grant programs, working on a SFMOMA commission, to remaining engaged with community organizing work in the still ever-forming SOMA Pilipinas. As I continue to grow in my hybrid administrative and artistic practice, I am cognizant of how certain communities look to me as a grant administrator, organizer, educator, community photographer, and archivist, and how to wield these existing legacies together. My various roles serve as reminders for the rigor I’ve developed to secure funding, partnerships, evaluation and documentation practices for the various community organizations and institutions I serve, which are now in direct dialogue for the first time. I also learn to witness, and listen, and move patiently and purposefully.

IY: You were recently commissioned to complete a body of work, My Ancestors Followed Me Here, by SFMOMA, now up in the exhibition Bay Area Walls. Since we’re on the topic of institutions, how did this project come about? How was that experience?

EA: My Ancestors Followed Me Here expands upon my ongoing investigation of anti-displacement resilience along Mission Street—a thoroughfare threading through Excelsior, Mission, and South of Market. I collaborate with artists Vida Kuang and Lourdes Figueroa to listen to the experiences of residents and shopkeepers along Mission Street during the COVID-19 pandemic and global uprisings. We archive these voices through my photographs, transcribed multilingual audio interviews, and a newspaper.

This opportunity to share work at SFMOMA comes at an uncanny time, when arts institutions are experiencing a collective reckoning. It’s been a blessing to work with curators Linde B. Lehtinen, Sally Katz, the larger SFMOMA team, and fellow exhibiting artist Adrian L. Burrell. With this team, I’m learning how to reconcile with this privileged opportunity, and how important it is for me to recognize the trust and investment that individuals like Linde and Sally have for me when I represent the communities who care for me as I sit at various decision-making tables.

Scatter Piece performance, 2019. Courtesy of artist.

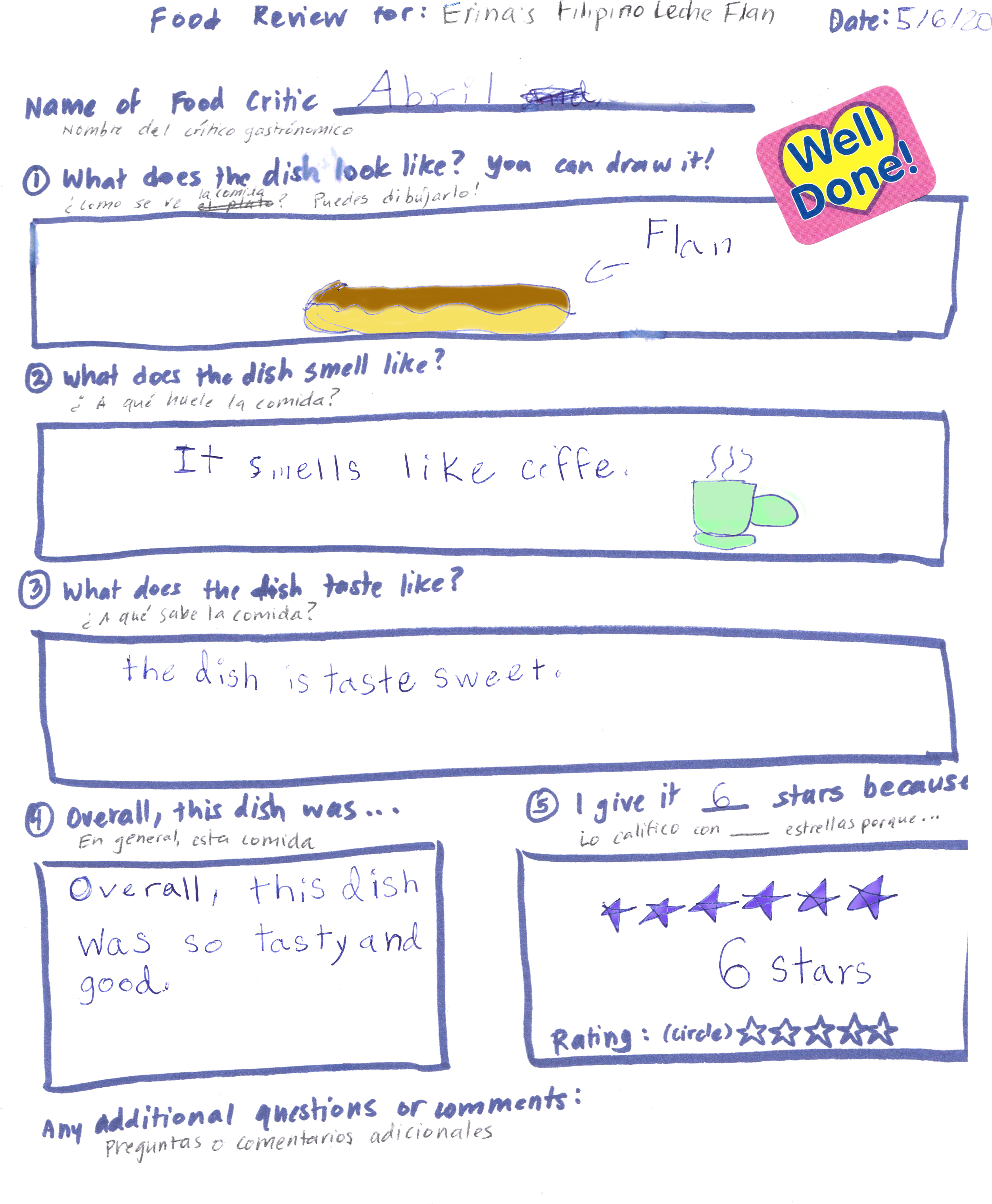

Alejo’s elemetary school age neighbor, Abril’s food review worksheet of Alejo’s leche flan dessert, 2020. Courtesy of artist.

IY: I would also imagine that representing these communities at decision-making tables, as you say, carries certain pressures or expectations when we think about how rarely Asian Americans are "seen" in the study of American art. I hesitate to say "Asian American art"–in general, I'm increasingly wary of labeling art by ethnic or racial categories–but we do need to address the lack of representation of Asian American artists. Like, is it possible for us to find footholds in art institutions without that feeling that we're just here to fill a quota? I'm wondering if you could speak to navigating this tension, particularly as you begin to establish yourself professionally.

EA: InHae with these questions! I can’t wait to read your future scholarship. Okay, bear with me here:

As I told you recently, I just started reading Susette Min’s Unnamable: The Ends of Asian American Art (2018), an insightful examination of how existing curatorial and institutional practices can both limit and help us create resilient futurities in discourse on Asian American art. (Min writes a gist of the book in a 2020 essay for Panorama.)

Asian American art has more to learn from cultural studies and art history across Black, Asian, and Latin American diasporas—basically, beyond the Eurocentric lens we’ve long relied on to understand and validate our art practices. I reflect on the cross-cultural solidarity of the 1968 Third World Liberation Front strikes across California campuses, which helped found Ethnic Studies at SF State and Cal, and the organizing work we continue from this legacy.

My very perceptive mom says that the burden of being American-born, queer, Filipinx, etc., is that I must live within and continue to resist labels, boxes, hyphens, and other forms of categorization as residues of empire and othering. I think it’s possible to gracefully balance this tension–for all of my identities of a gem to sparkle at different angles. At SFMOMA, Linde and I deliberated on my artist label. Did I want to put “Erina Alejo, Filipino-American, b. 1991”? I consulted Lian, who assessed, “Unfortunately, you’re American. Vito Acconci wouldn’t put Italian-American. But put Filipino-American in your bio.”

I took up Lian’s advice because I agree that the American discourse, not just its diaspora, should reflect my work. Hence, more encompassing. As Min expands, there’s also a certain power in leaving an art unnamable. In relation, I think of ethnographic refusals as a profound method, where participants collectively decide to omit knowledge granted to an institution, with respect to the researched community’s right to self-representation. I often encounter refusal due to the nature of my work—gratefully so, because the opportunity to challenge my inherent lenses and assumptions makes for a more rigorous work centering who I’m listening to.

IY: Real talk. When you boil it down, it’s just a basic matter of courtesy–just ‘cause you can research or photograph someone, doesn’t mean you should. Plus, not everyone has that privilege of access necessary to make work about whatever they want. Jay Simple’s essay, Why Intent, captures this idea really well. I also touch on ethnographic refusal and archival silence in Navigating Alterity.

To wrap up–what’s got you inspired right now and looking forward to 2021? Things that you’re reading, watching, consuming? Or upcoming projects?

EA: Outside of ever-consuming projects, I’m finishing up my audio book of Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower so I can read some of N.K. Jemisin’s work. I’m consuming a lot of sea water, too! I surf pretty frequently, and it’s been hashtag, #ragdollseason with the large Pacific Northwest swells coming through the Bay Area. It’s NBA season and the consecutive games have been blaring in the background as I respond to your questions—I am forever fascinated with the American idolatry of athletes, and the over-scrutinization of their movements, personalities, and place in history.

This shelter-in-place during the ongoing pandemic has also helped my loved ones and me embrace leisure, and pare down. What? Rest can exist, despite all the heaviness going on in the world? I’m very privileged to have a roof over my head, to be able to work remotely, and be with family. I never imagined it was possible to see my houseplants grow leaf by leaf, to see my mom be able to sleep in, for me to bake cookies with M&M’s, specifically requested by my kid neighbor.

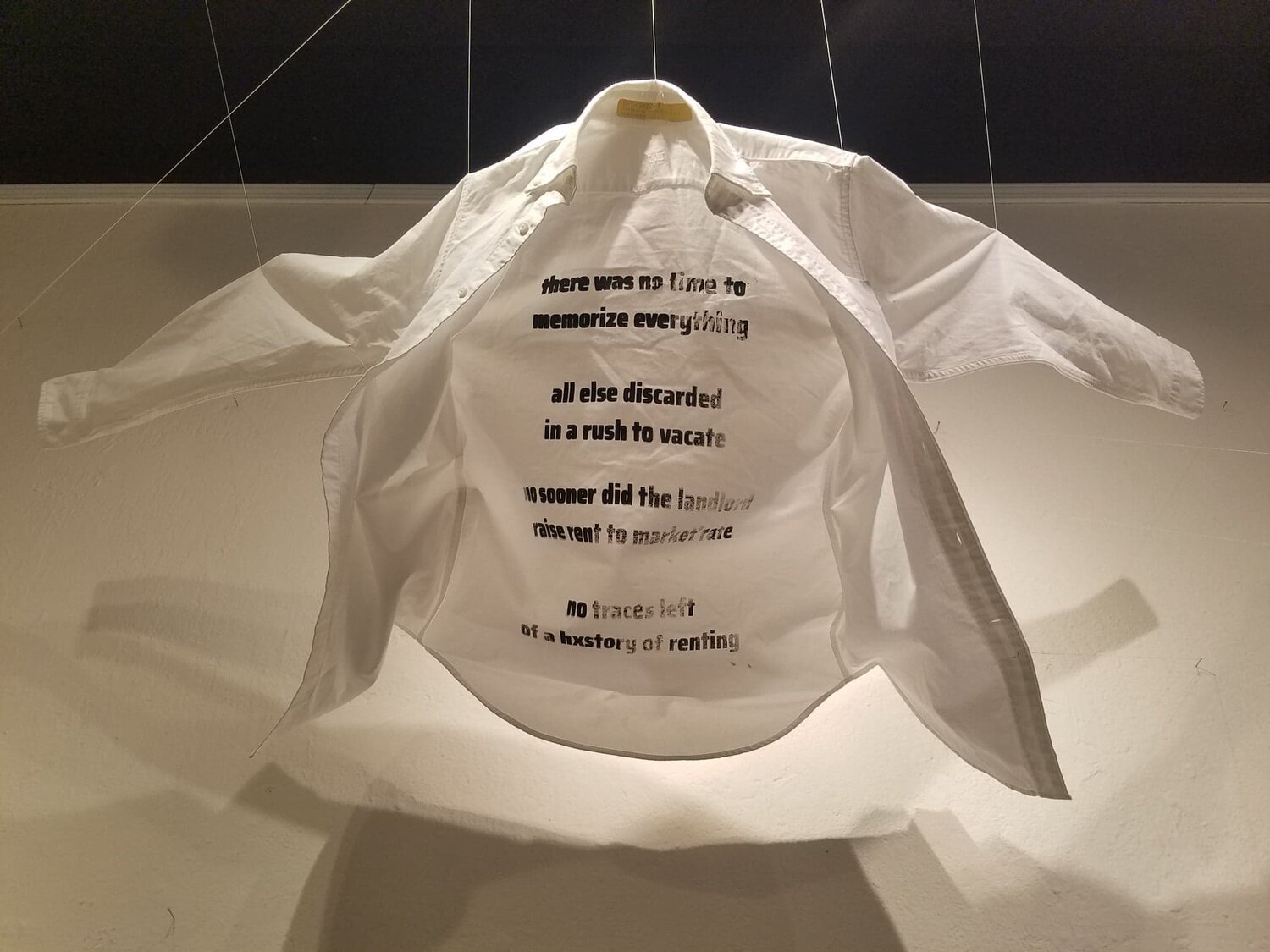

Untitled (grief is a weightless thing), 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

[1] I’m endlessly grateful to collaborator Lian Ladia who has been championing AHOR as a body of work for a long time with Jerome Reyes and David Woo, the femtorship of Janet Delaney, the fresh eyes of our book designer Jerlyn Jareunpoon-Phillips, and the support of clamshell press. Lian, Jerlyn, and I have been in correspondence for over one year across two continents over the book design and edits. Jerome, David, and Janet all graciously contributed their words, punctuated as essays across the three-chapter book. –EA