Q&A: Clarissa bonet

By Jess T. Dugan | October 13, 2016

Clarissa Bonet lives and works in Chicago. Her current work explores aspects of the urban space in both a physical and psychological context. She received her M.F.A. in photography from Columbia College Chicago in 2012, and her B.S. in Photography from the University of Central Florida. Bonet’s work has been exhibited nationally, internationally, and resides in the collections of JPMorgan Chase Art Collection, the University of Michigan Museum of Art, The Museum of Contemporary Photography’s MPP collection, the Southeast Museum of Photography, and the Haggerty Museum of Art. Her work has been featured on CNN Photos, The Wall Street Journal, The Eye of Photography, Photo District News, Juxtapoz Magazine, and many other notable online and print publications internationally.

Bonet has received recognition and support for her work from the Individual Artists Program Grant from the City of Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs & Special Events and Albert P. Weisman Foundation. Recently, she was chosen as one of PDN’s 30 New and Emerging Photographers to Watch in 2015 and selected as a 2016 Flash Forward Emerging Photographer by the Magenta Foundation.

Clarissa is represented by the Catherine Edelman Gallery in Chicago, IL.

Jess T. Dugan: Let’s start by talking about your City Space project. How did it begin and what inspired you to begin making these photographs?

Clarissa Bonet: I grew up in Florida and prior to moving to Chicago it was the only place I had ever lived. I was used to a warm, lush, tropical, car-cultured way of life, so you can imagine what a shock it was to suddenly be living in Chicago. It was simultaneously thrilling and intimidating. The landscape felt wholly foreign—the sheer expanse of the city, the anonymous individuals that I would never see again, and the large swaths of concrete that covered the surface of the city. It was challenging to deal with at first; I had never felt so insignificant. To understand this new landscape and my place within it, I started making images about it and my experience of it, which eventually turned into City Space.

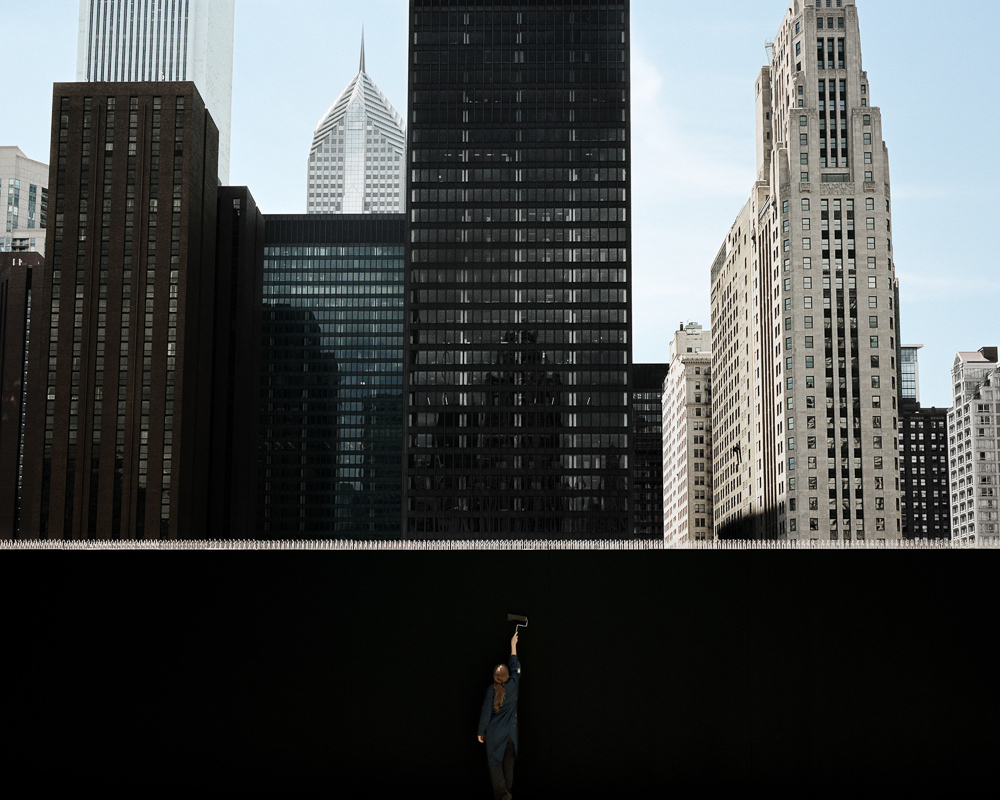

From City Space

JTD: One of the things I love about the images in City Space is their simultaneous connection to a real moment or experience and their formally elegant, almost cinematic nature. Can you talk about the process of making these images and the ways in which you come up with an idea, find a location, cast models, and ultimately make the photograph itself?

CB: The shift in my daily routine from the car to the pedestrian had a huge influence on my work and practice. I found that on foot I had a deeper connection to the city, specifically the street, and my experience of it. Mundane experiences of daily life became pronounced and I saw the beauty and strangeness in these ordinary moments that are often overlooked. My aim is to make images about the experience of the city, not to document it. There is something lost in translation between a photograph of a moment and what that moment felt like. I aim to image the latter and that is why I construct my works.

I borrow from the genre and practice of street photography. I take to the streets by foot, roaming the surface of the city for hours at a time, reacting to what comes across my path. But instead of making my images when these events come to light, I stop to observe them, take notes in my sketchbook, and make a few snapshots with my iPhone. I consider these snapshots my sketches. Then, once back at my studio, I look over the material collected and start to piece the final photograph together.

From City Space

Sometimes during my wanderings I find a location I really enjoy—and keep it for months before I find an idea that is best suited for the location. Other times I have an idea and spend weeks looking for a location to make the image. I am inspired by personal experience or things I witness in public, but often the location where these happenings take place is distracting visually and I want to isolate the event to encourage the viewer to consider just this one act or moment. This is why I don’t just make an image of what I experience on the street in real time. We as viewers can isolate what we see in real space, but in a photograph time is frozen and the viewer takes into account everything that is in the frame when trying to understand an image. With my images, I have a specific reason for making them and aim to move the viewer to that point. By constructing images I can be extremely specific; I can allow the viewer to see what I want them to see, thereby making the image reference one specific moment and what that felt like—not just what it looked like.

Once I have the details as to where and what the image is going to be about, I choose clothing and props, then cast individuals for the image. Sometimes I use friends but more often I hire people through Craigslist. Usually, I put out a general call looking for individuals, with no experience necessary, although many who respond tend to be actors. This is great because they take direction well. Once I cast people, we go over wardrobe. I like to use as much of their own clothing as possible but often shop for items to obtain a specific color or outfit. Then I explore props, which come last. Shopping for props is a favorite task of mine.

So as you can see from my response to your question, it’s a lengthy, involved process although the image may look to be effortless in construction, which I like. I want the image to speak first and not its artifice. This is definitely a calculated decision.

From City Space

JTD: Ray Metzker is one of your most significant influences. Were you aware of him prior to moving to Chicago or did you discover his work then? How do you view your work in relation to his?

CB: Prior to moving to Chicago I had no idea who Ray Metzker was, and I think a lot of people outside of Chicago probably still don’t. While I was in grad school, I came across his work while doing research. I was trying to find photographers that were making images of the city not as mere descriptions of the constructed landscape but instead of the emotional and psychological connection to the place, which I am ultimately trying to get at with my images. His work achieved that. I am trying to image something that is intangible in a way. When I found Metzker’s work it was absolutely life changing. He used the language of photography to transform what was before his lens. Mainly, he did this with light. But I soon started to think of all the other ways I could achieve this as well. I then started to think about light of course, but then also about color, or even the lack of color as a device, as well as camera placement, and even atmospheric elements like water or fog.

There is no doubt that Metzker was a huge influence on my work and I see my work alongside his, furthering the conversation about the urban experience, the photographer’s relationship to the street, and the genre of street photography.

From City Space

JTD: You reference your connection to street photography, a genre largely dominated by a certain type of male photographer. Given the mission of the Strange Fire Collective, I’m curious to ask: how does being a woman working within this realm affect you? Is this something that factors into the process of either making or exhibiting the work?

CB: Over the years making the work and talking about it, I have had strong opposition to the way in which I make images—almost exclusively from the male perspective. I don’t want my images’ artifice to be the only thing that is discussed, although sometimes it has seemed to be the case, and I am certainly not trying to hide my process. I don’t think I should have to. I am intentional with my decisions and think this is one of the aspects of the project that makes it strong. I am expanding upon one of the oldest genres of photography—street photography of course—and bringing it into the contemporary moment. I am aiming to expand the conversation, not break it down, but some people can’t get past the fact that I do not make images from the chaos of real life in a traditional sense.

I do have to say that making images on the streets as a woman may be an advantage. I very rarely get stopped or kicked out of locations, even when I have a rather extensive setup. I can think of specific instances when I was partially blocking the street or sidewalk, situations where this was quite obvious; however, a female with long curly hair seems to be perceived by most people as non-threatening. Most just leave me alone to do my thing. To make images where I am shooting through a window, I have set up a large piece of Plexiglas on the street, approximately 4 feet by 5 feet in dimension, clamped to two C-stands. In addition, my setup has included models and a tripod for my camera. Both times I used this setup, I had no issues. Although that having been said, I have had the occasional confrontation with a security guard, which is bound to happen when you have been making work on the streets like I have for the past six years. For the making of the work it’s a blessing to be a woman, but when it comes to presentation of the work I still get pushback.

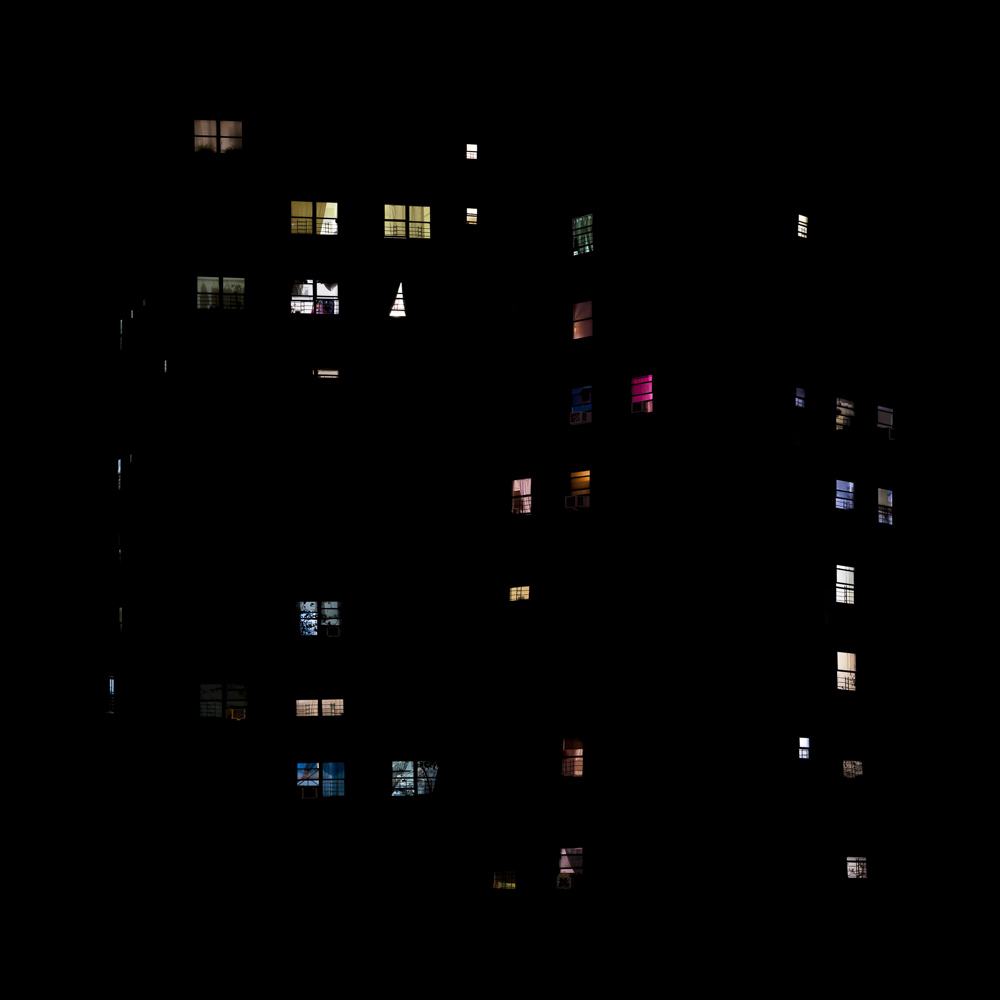

From Stray Light

JTD: Tell me about your Stray Light project. What inspired this series and what is your process behind each image?

CB: A few years ago I found myself spending a lot of time in the city at night. I was fascinated by the shift in my perception of urban space and how the city transformed as night fell. By day the city is a unified front and the facades of the buildings dazzle with beauty and strength. They are impenetrable, perceived as solid structures. But as night falls the city is transformed. Light emanating from the windows reveals glimpses of those who reside inside. This perception evoked the same emotions I feel when experiencing the natural night sky in a “Dark Sky” area. I became inspired by the beauty, the mystery, and experienced a deep sense of awe. I started to think about the absence of the stars in the night sky above. For the past seven years I have lived in Chicago and it’s surprising how little I thought about what was missing from the night sky until I stated working on this project.

In the beginning of the project I experimented with process and soon realized that a one-to-one representation of the urban landscape at night was not what was needed to capture the beauty, mystery, and awe. I started focusing on the stray light that emanates from these windows. This light speaks to the individual life that resides inside, which incites the mystery.

To make work for Stray Light I gather data—photographic images of the buildings. I photograph from a variety of vantage points: parking garages, balconies, elevated streets, office windows. I have created an archive for this data and add to it regularly. After amassing a large amount of data, I pull from this archive to make collages. Hubble telescope images provide inspiration—of scale, density, depth, color—as I collage the work together to create images referencing the cosmos.

The glow that is created from these windows produces a barrier between us and the real star systems above. This beautiful, mesmerizing but artificial nocturnal landscape speaks to progress in modern times. The collages that I create are representations of the celestial light that we have created on earth.

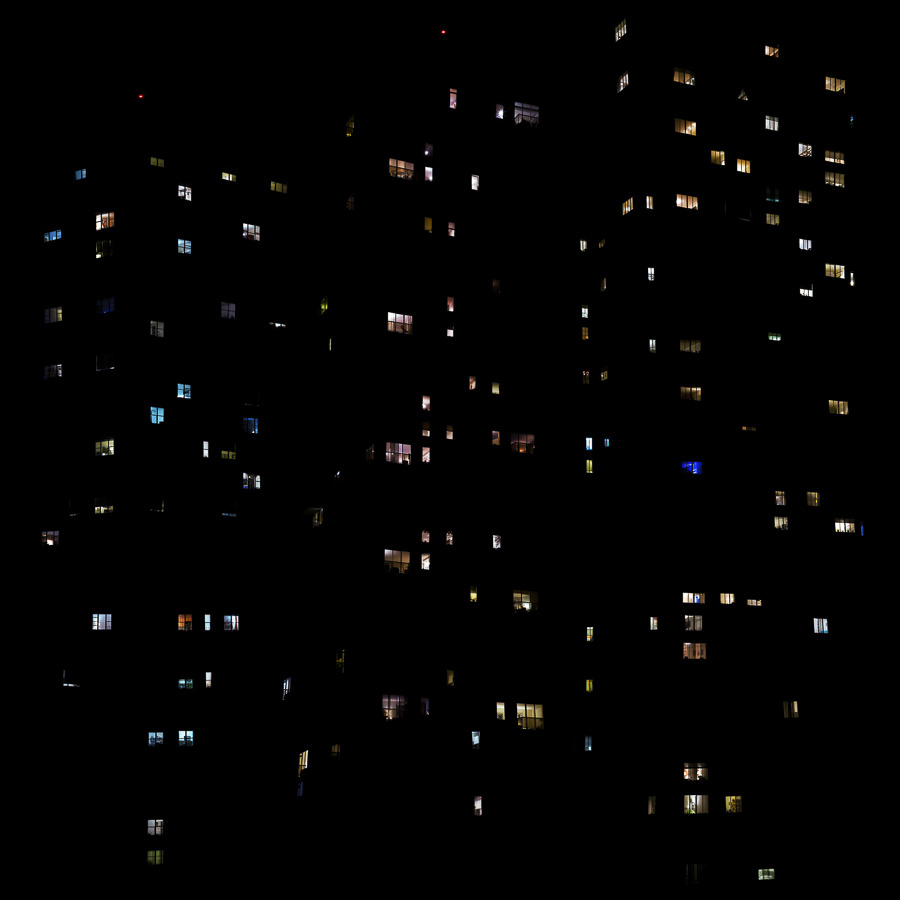

From Stray Light

JTD: Your process of taking thousands of source images and combining them into a single photograph sounds completely overwhelming to me. How do you keep your image archive organized and how do you know when you’ve gathered enough material to create a finished piece? Further, how do you decide when a Stray Light piece is finished?

CB: At the beginning of the project it was so hard to keep everything organized. When I first started making the images I had no idea how complex they would eventually become. But once I started to realize I needed to come up with a strategy and system, it became a lot easier to stay organized. I keep everything organized by separating the images by what city they were shot in; then I categorize them into three folders based on what the images are of: isolated groups of windows, whole buildings, or reflections. Then they also get color-coded based on the sharpest image, since I bracket for each image. They get a different color-coding if they have people in the windows, and then finally they get another color if they have been used in a collage previously.

I tend to shoot for weeks or months at a time and then process everything at once. Chicago can have harsh winters so I try not to spend time in the studio on good days where I can be outside making work. So I tend to do all my shooting when the weather is nice and all my editing in the winter so I can hibernate, making images when it’s below freezing, technically challenging, and tough physically. At times, the amount of data I have to process can be overwhelming.

From Stray Light

After initial processing of large batches of images, I then start to piece together the final image. Sometimes I can pull from my archive of what I’ve previously shot and an image comes together quite quickly; other times I have to keep going out and collecting more imagery to finish the piece.

Each image goes through multiple iterations before I decide when it’s finished, which can be challenging to decipher at times. When I feel really good about a piece I usually put it away for a while and let it simmer in the back of my mind. If I come back to it in a week or two and still feel the same, then I make a print of it at scale (42” x 42”) and see how it holds up. Usually, I tweak some aspect of the image in this stage, and then repeat this step until I’m satisfied. Then I put the image away for a few more weeks and come back to it one last time. If I’m still happy with it then I consider the image complete. Having the ability to print in my studio has benefited my process tremendously. I have to be able to see the work at full scale because no matter now much time you spend with an image, it changes drastically when you see the image at its intended size.

JTD: Where do you find inspiration?

CB: I find inspiration mainly from walking and observing daily life. At least 1-2 times a week I try to devote myself to roaming the city’s surface. I so much enjoy spending time just looking and thinking about the mundane aspects of life. Most of the time I am not looking for anything in particular. I’m just attentive to what presents itself to me. You would be amazed at the interesting things you can observe if you take the time to just look.

City Space + Stray Light at the Catherine Edelman Gallery, 2016

JTD: What projects or exhibitions are on the horizon for you?

CB: Currently, I have a solo show up at the Catherine Edelman Gallery in Chicago. It’s my first solo show at the gallery since they signed me to their roster a year and a half ago. I am exhibiting both bodies of work that we have been talking about here: City Space and Stray Light. City Space speaks to the horizontal, daytime, pedestrian experience of the surface of the city, while Stray Light speaks to the nocturnal, urban landscape. Since signing with Catherine Edelman, I have been working feverishly to get ready for the show. I’m really excited about this show because it is the first time my Stray Light project has ever been exhibited. For the past year I have only showed one or two pieces from the project at fairs. It’s exciting to see the work up on the walls after years of living with it on a screen and in my studio.

This past year I have also been exploring the beginnings of a new project that I am really excited about, but it’s still very new so I am not ready to divulge much about it yet–except that it exists. I tend to be guarded about my images; I like to live with my work for a long time before releasing it to the world.

All images © Clarissa Bonet / Images courtesy Catherine Edelman Gallery, Chicago