Q&A: Anthony Cudahy

By Rafael Soldi | July 12, 2018

Anthony Cudahy is a painter living and working in Brooklyn, NY. He received his BFA in 2011 from Pratt Institute, and co-curates a publishing project named Slow Youth. In 2018, he exhibited a body of paintings entitled The Gathering at The Java Project in Brooklyn and has shown at Farewell Books (Austin, TX) and Mumbo's Outfit (Manhattan, NY). He has been in group shows at Danese/Corey, MULHERIN NY, Practice, Harpy Gallery, and ATHICA, among others. His work has also been featured and reviewed in publications including Mossless, the Paris Review, Hello Mr., Marco Polo Quarterly, and Cakeboy. He is a former resident of the Artha Project. Dashwood Books produced a zine in 2017 of Cudahy and his husband, Ian Lewandowski's, work.

Anthony Cudahy / Nick Van Zanten at the Dawn Hunter Gallery

Rafael Soldi: As part of your process, you research and form an archive of reference images, which you then re-visit, reflect on, re-imagine, and expand on though paintings. In an almost reverse-research you produce multiple readings on a single image, rather than one reading based on multiple sources. How did this process come about, and why derive so many readings from a single image or collection of images? Where do you source your material from?

Anthony Cudahy: I've always been an avid collector of images. It's a sentimental action. Any collecting involves some tenderness on the part of the collector. I have a great love for the images I hold onto whether it's from my own family archive, random images spiraling down the internet, other painter's paintings, or (especially) recent searchings through specifically queer archives. Something happened to me that I think a lot of queer people can relate to. I just found out that my mother's uncle was an out gay man who owned an antiques store in Manhattan in the 70's. I was shocked that I had never heard anything about him or his partner. To my mother's credit, she had a exceptionally difficult relationship with this man who was terrible to her. Still, this figure from my family is an important piece of my story. I've been researching to the best of my ability about him, and all that I've placed together so far is the address of his Fire Island house and a copy of a check a famous actress wrote to him. The search here feels very similar to when I go through these archives. I'm looking for something unknown and unspecified, that feels necessary to figuring out something about now.

I'd like to think that the past isn't so fixed as we tend to accept. Stories broadly understood are hardly ever nuanced. Marginalized groups will be brushed aside or intentionally erased and diminished. Considering the past is an active mode, full of potential. There's work to be done in uncovering. Some of the duplicates and versions of images I paint is me thinking about the past in this way.

Painting in multiples also helped me to understand that you don't have to do everything in one painting. I feel more free to try out a color or paint-handling idea when I know it's not my only go at the image. And sometimes an image is so potent and has so many angles to it, multiples just seem a given.

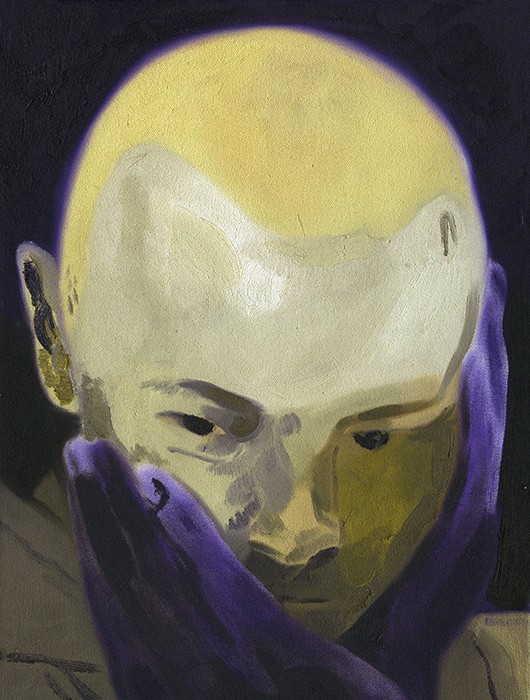

vigil 2, oil on canvas, 18" x 30", 2017

RS: Many of your bodies of work draw from dark rites such as vigils and funerals. What attracts you to these?

AC: The second I began to focus on queer image archives, vigil after vigil would appear. I imagined painting a long chain of individual paintings, each looking as if it was from the same vigil while the sources spanned decades, grieving the individual losses and the systemic damage. I wanted to create a loop, eternal return and repeat—a place to grieve.

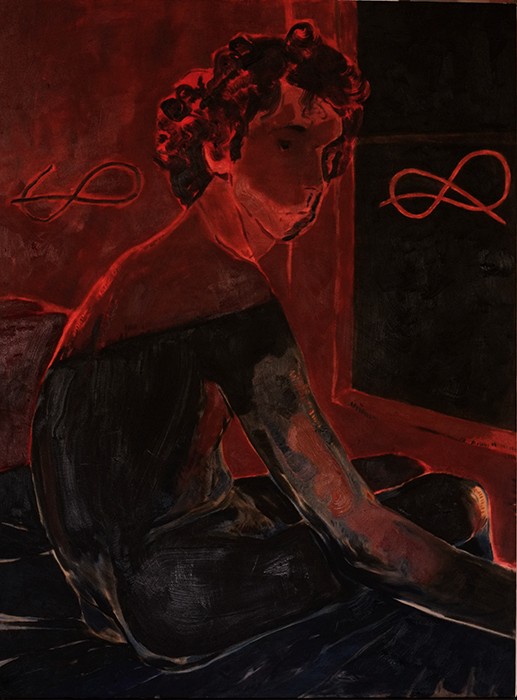

RS: At some point in your research you stumbled upon—amongst many sad or tragic images—a jovial image depicting a large group gathering for a 1970's gay and lesbian camping retreat. This was the subject of your body of work The Gathering. Can you talk about this shift and why it was important to focus on this image? What was the result?

AC: I very quickly grew weary of only presenting this mourning. Also I had been looking for a complex group shot to paint for a long time, and when I came across the Pat Rocco image of the retreat in the hills of California, it was magic. There were several other group images from this specific trip but none of the others hold whatever it was that captivated me and triggered my project. I created two very large paintings, splitting the scene in half. The vertical one treated each person as their own universe to be handled uniquely (I was thinking a lot of Nicole Eisenman's recent painting, Another Green World). The other horizontal painting created a false lighting source, a difficult-to-place fire. I thought of Goya’s witch paintings. The scene to me became less a specific place-in-time as I worked through it, and more an almost mythical scene, a gathering of important figures. Something essential is being worked out. I wanted there to be a utopian feel, thinking of early early gay liberation thinkers, who were more radical in their aims. It was important to me that genders weren't fixed on every figure.

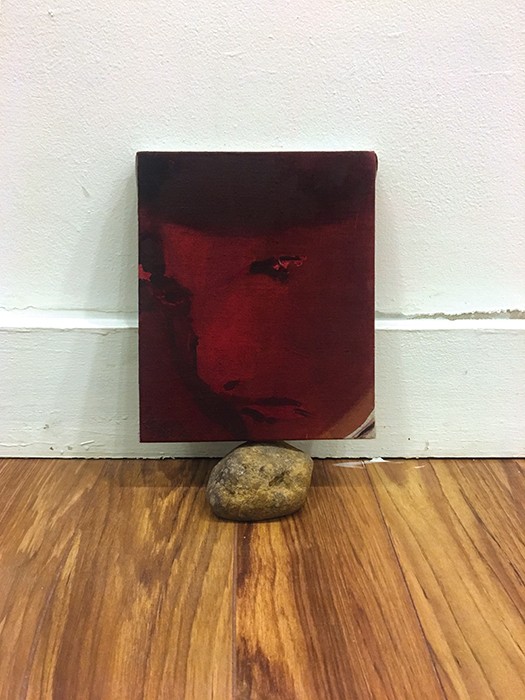

From The Gathering

These paintings aren't necessarily joyous images, but they also aren't literal scenes of mourning. There's a complexity of life lived in them, of interactions amongst individuals. In addition to the two large paintings, I made several smaller paintings and works on paper, expanding and contracting the scene, sometimes with a fidelity to the source and sometimes expanding and adding symbolism. One figure became a flower-collector as I continued to paint them. Certain interactions were highlighted. Faces merged, in and out of focus. It was all I painted from in the second half of 2017 and still it doesn't feel exhausted. There's more to be found.

RS: You've collaborated with your partner, photographer Ian Lewandowski. Can you expand on this collaboration?

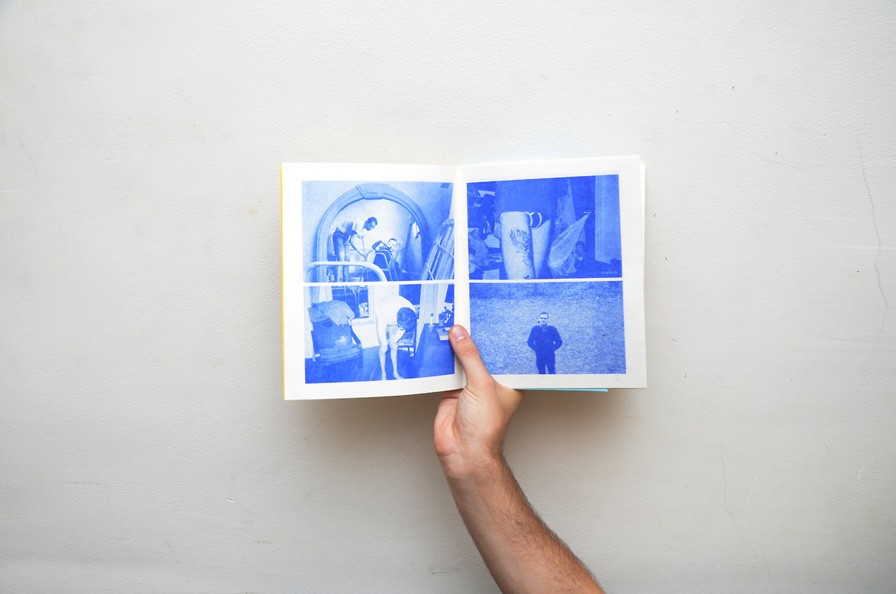

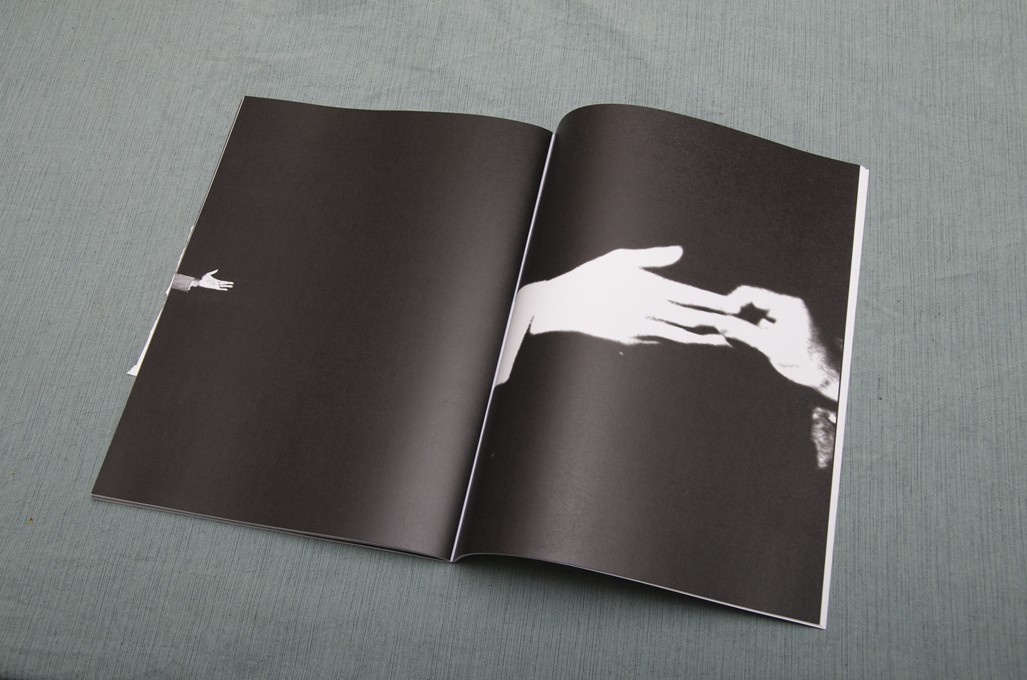

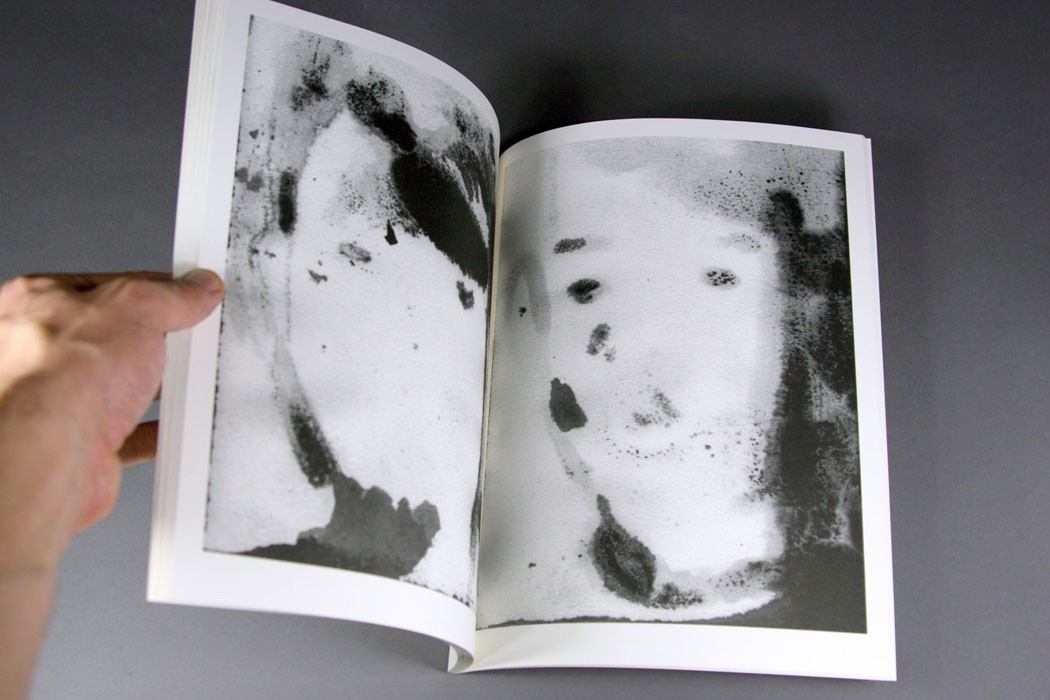

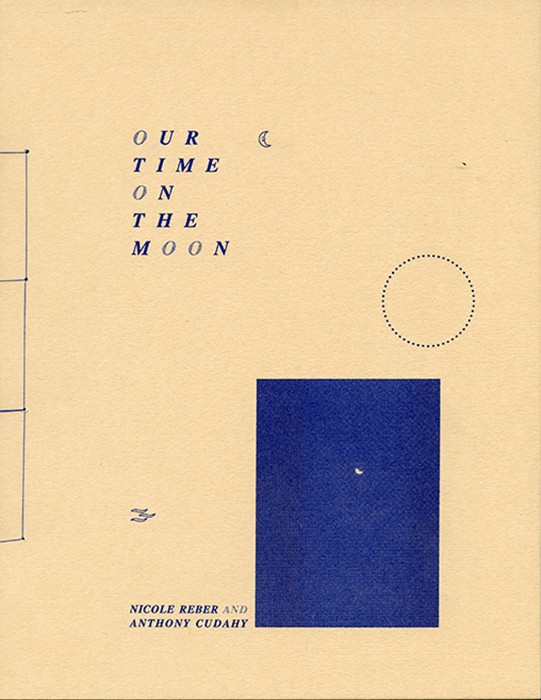

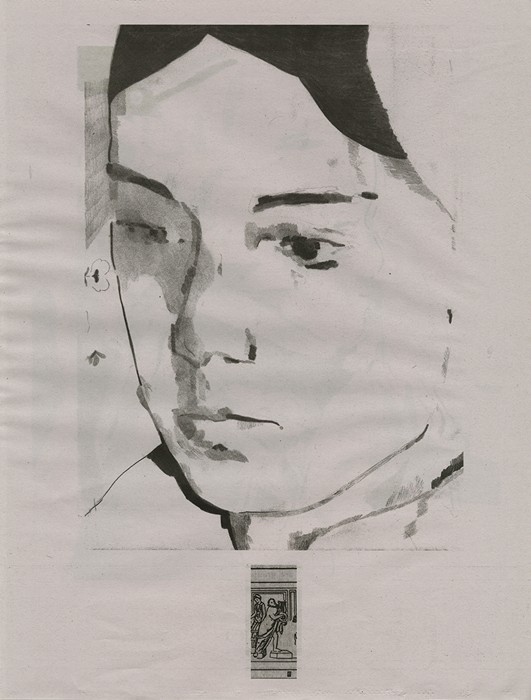

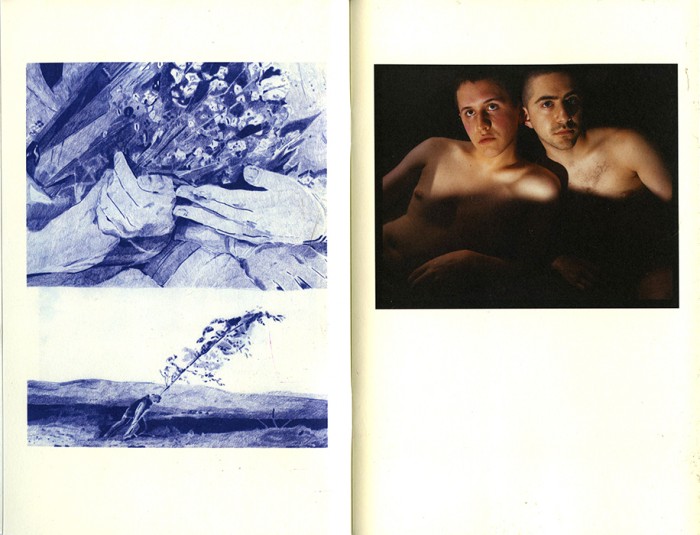

AC: Ian is the person I speak to the most about whatever it is that I'm working on, and I'm that person for him as well. Our practices are intimately tied together. We talk through our ideas, as well as push and challenge one another. Luckily, last year Kat Shannon (for Dashwood Books) curated a zine of Ian and my work where our practices were presented side by side and interacting for the first time. I think it gives a context to and raises the stakes of both our work. Some of those vigil paintings were in that book. Most of what I mentioned above about working with archives and viewing the past as a place of potential, is clearly present in Ian's photographs as well.

Recently, we've been scheduling visits to the Center's archives. As we make our way through Out Week's collection of images, we're both beginning to make works in response to some of the photographs we've found. This is the start of a hopefully long-term collaborative project between us.

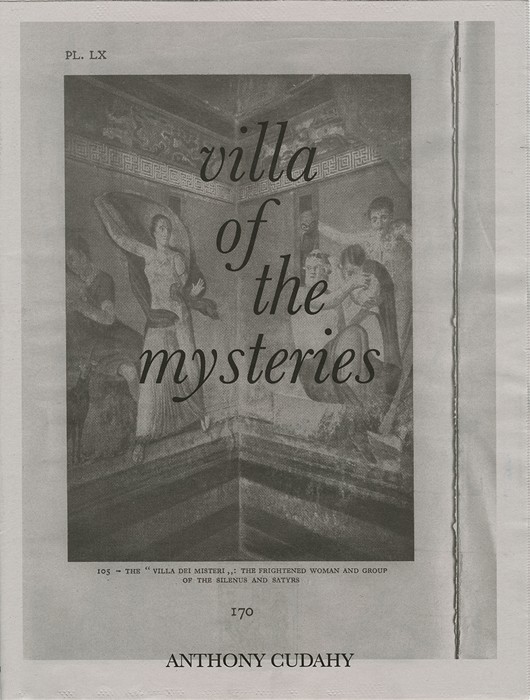

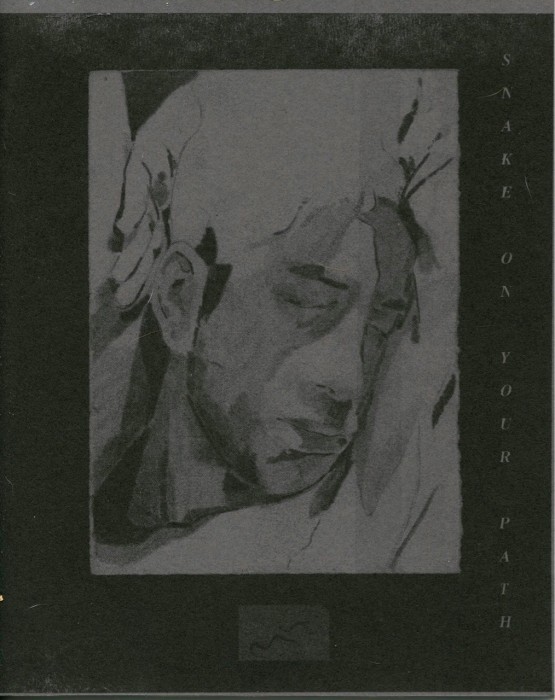

igil (Rhythm) Vigil

Anthony Cudahy & Ian Lewandowski

New York: Dashwood Books, 2017

250 Copies

RS: Painting and photography have always had a unique relationship. What are basically one of the oldest and newest art forms respectively. Many of the greatest photographers in history began as painters and fell in love with their reference material, the photographs. What is your relationship to it, if any?

AC: I've always been drawn to photography, and the visual language inherent to it. A caste shadow, or a pixelated degradation. I don't necessarily see it as opposed to a painting practice, but instead as more visual language I can reference in my work.

Extremely rarely do I take my own reference photographs, and when I do it's usually an image I "discover" later on. The set-up and composing on that end isn't very fruitful for me. I work best in a sort of collage method, finding pieces and creating visual shorthand for concepts.

RS: Zines and self-published books are an important part of your practice, offering an outlet seemingly in contrast to painting: they're cheap, infinitely and mechanically reproducible, low brow, accessible. How do each of these elements enable your practice, and how do they intersect?

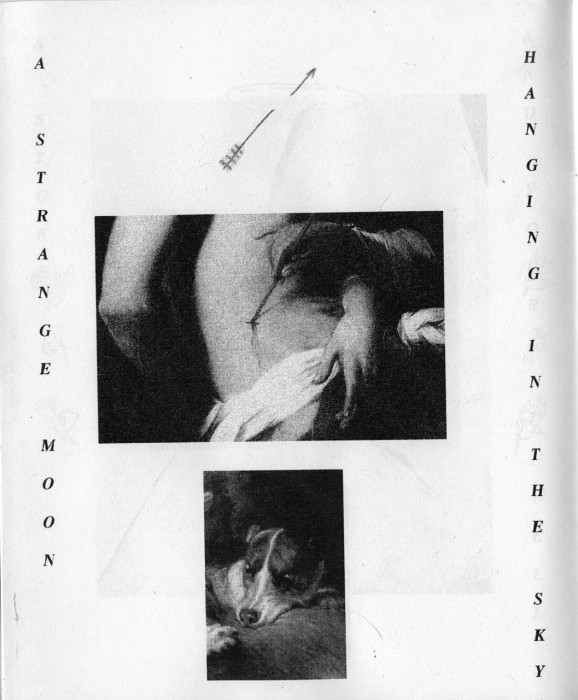

AC: For a long time, the two practices were clearly demarcated, and I thought of them as really different lines of thinking. The freedom of juxtaposing various kinds of images and mediums in the zines eventually spread into how I structure paintings.

The zine format is still so potent for me because there's the ability to pace and make comparisons between a ton of various elements. It's personal, and fetishistic in a way that might be considered antiquated, but it's something deeply satisfying about the medium.

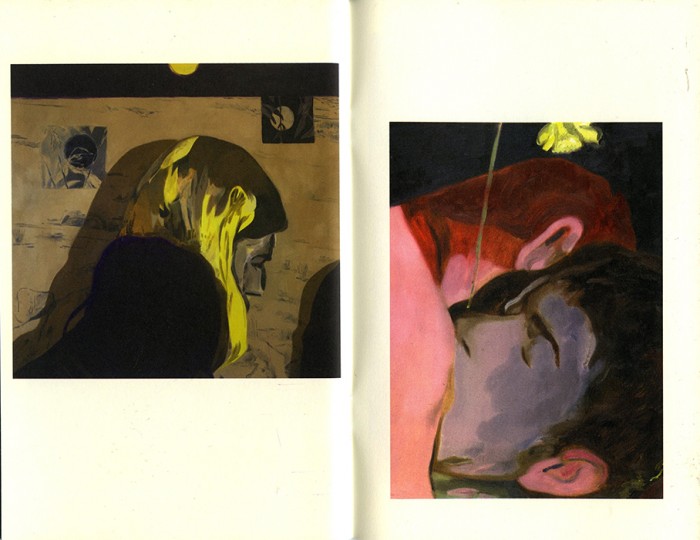

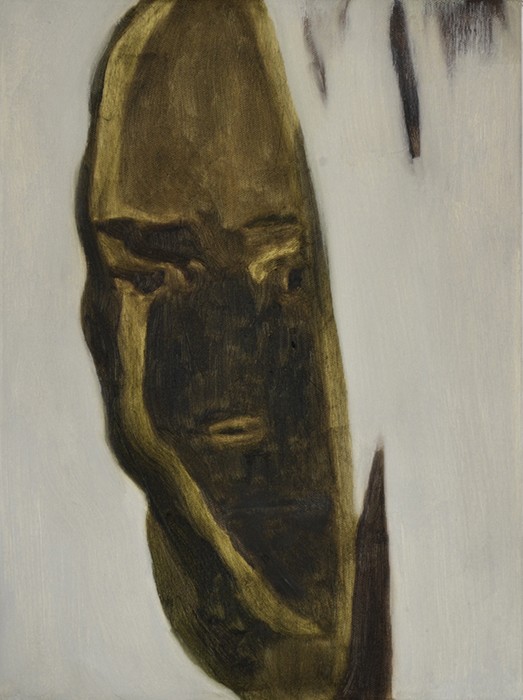

RS: Let's discuss some of the formal elements in your work. Your paintings mostly depict people, often narrowing on faces, but also in groups. The figures often remain unfinished, swaths of color bleeding into one another, nearly face-less faces. More often than not your palette is meek and turbid, with figures punctuating the scene, glowing as if by divine intervention. How did this aesthetic approach come to be? Who has inspired your mark-making?

It's funny, the bank you keep with yourself as an artist creating over time is very persistent, but slow-moving. You'll be painting and all of a sudden realize, that's how they made that mark! It'll be a painting you took in and loved years before, and it required that much time and work to get to, the painting sitting in the back of your mind all the while. In this way, I feel artists I love take a long time to work their way out in my work. I get Luc Tuymans comparisons often. He's great, and was supremely important to me at a certain point, but it's been years since I really really looked hard at his work. Jennifer Packer and Josephine Halvorson are painters I really hold dear at the moment. Lois Dodd. Like I said above Nicole Eisenman. Philip Guston.

The process of painting for me often results in minimizing the color palette as I work, until often many details merge or become a bit less certain. This is also how the paintings tend to have areas that glow. Usually the entire painting was once that saturated and slowly it becomes something a bit more dense with scattered areas of phosphorescence. I need a certain feeling of openness that's hard to pin point. I think a lot about stopping. It's a balancing act, but sometimes one unneeded mark can destroy the painting. It'll veer into being over-rendered and die. I want my drawing to be apparent in the marks. Mostly it's walking a tightrope between the surface of the painting and the image being represented. For me, they're always in some sort of conflict.

RS: What's next for you?

AC: In July, I'm part of a group show I helped curate at 1969 Gallery alongside the director, Quang Bao. The artists include Anna Glantz, Heidi Hahn, Ian Lewandowski, Kim Westfall, Eric Wiley, and Nicole Wittenberg.

Then in September, I'll have a solo exhibition also at 1969. This is what I've been working towards. I'm in a good place, the work is flowing, but there's a ton to get done.