Q&A: Ann Johnson

By Hamidah Glasgow | September 24, 2020

Ann' Sole Sister' Johnson Born in London, England, and raised in Cheyenne, WY, Ann is a graduate of Prairie View A&M University in Texas (where she now teaches) and received a BS in Home Economics. She received an MA in Humanities from the University of Houston-Clear Lake and an MFA from The Academy of Art University in San Francisco with a concentration in printmaking.

Primarily a mixed media artist, Johnson's passion for exploring issues, particularly in the Black community, has led her to create a series of evocative and engaging works such as It Is The Not Knowing That Burns My Soul, which is an investigation of exploratory mixed media works that examine the Black Indian. The series was included in an exhibition and catalog for the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian titled: Indivisible. Ann's work has been exhibited nationally in solo, group, and juried exhibitions. She was a Prize winner in Houston's "The Big Show" in 2004 and was the Mixed Media winner in the Carroll Harris Simms National Black Art Competition in 2007. Johnson was also included in the Texas Biennial in 2013. Recently, Johnson has focused on experimental printmaking, and in 2015 she was acknowledged as an "Artist to Watch" in the International Review of African American Art.

She has exhibited at The Museum of Fine Arts Houston, TX, The Museum of Printing History, Houston, TX, Women and Their Work Gallery, Austin, TX, Project Row Houses, Houston, TX, Tisdale Beach Institute, Savannah, GA, Charles H. Wright Museum, Flint, MI, The Apex Museum in Atlanta, GA, and The California African American Art Museum in Los Angeles, CA. Ann' Sole Sister' Johnson aspires to leave a legacy of challenging and thought-provoking work that will entice the viewer and inspire younger artists. Texas Representation: Hooks Epstein Galleries, Houston, TX

HG: Thank you for taking the time to chat with me. Tell me about your trajectory as an artist?

AJ: I am influenced by my mother, who is 83 and an avid gardener and oil painter. Art and being a creative thinker have been a part of my entire life. I earned the name Sole Sister because I paint portraits with my feet. I now focus on experimental printmaking. I majored in Fashion initially and eventually realized that art was and is my true love. I Attended Bauder Fashion College in Arlington, TX (AAA in Fashion Merchandising), BS in Home Economics from Prairie View A&M University, MA in Humanities from University of Houston-Clear Lake, and an MFA from the Academy of Art University. I have exhibited and curated locally and nationally in a variety of spaces (see attached CV).

HG: Some of your work uses images of Delia from the Zeally Daguerreotypes. What brought her into your life and work?

AJ: I have been infatuated with the images since Carrie Mae Weems created the piece "Scientific Profile," which was one of the first works of art that made me cry. Naturally, I immediately thought of Sarah Baartman, but more importantly, the idea of the woman in the photo being so powerless. She had no power or no rights to say, "no, I am not gonna take off my clothes for your experiment, research or examination." She had no voice over herself. Last summer, I did two exhibitions that examined slavery. Harvest at the Houston Museum of African American Culture, Acknowledge at Hooks Epstein Galleries, and Soren Christenson Gallery in New Orleans. This when I began experimenting and printing on raw cotton. This is also one of the few times that I printed someone that I did not have direct contact with, but of the presence of Delia lives. I again focused on powerlessness, which led me to create a few pieces that examined the history of gynecology. To make things full circle when I spoke about my motivation for the works that focused specifically on gynecology and using Delia's image, more than one person came to me in tears. Ain't that a trip.

HG: The Zealy daguerreotypes are unique and carry a heavy legacy of the enslaved sitters and the problematic man, Louis Agassiz, who commissioned the portraits. I would find it odd that anyone can look at them and not be touched deeply. It’s wonderful that you’ve been able to keep their legacy alive through your art and allow people to know their story. We need never forget the terrible history of this country.

HG: Tell me more about your work around gynecology? I know that the history of gynecology is highly problematic for BIPOC women in this country.

AJ: I was in a school meeting, and a professor talked about the notes that Dr. James Marion Simms. As he mentioned his "subjects" by name, Lucy, Anarcha, and Betsey, it struck a chord with me, and I wanted to give them a voice. I was so disgusted by his cynicism as it related to how the young slave's girls reacted to the pain, as they were butchered in the name of science. As I read about him, I thought of Delia and Dranna from the Zeally portraits, and all I could think about was how these women were used as experiments. And how accessible they were because they were chattel. They were property. This is the beginnings of printing on cotton, which of course, links to a direct connection with slavery. I also printed on medical gauze, which created a very haunting print.

HG: Your grandmother was a Black Indian; I'd like to hear more about her and her influence on you and your work.

AJ: My father's grandmother was known as Indian Emma or White Emma. We had this image on the wall of family pictures with her with these two long braids. I was always fascinated with that pic. Growing up in Wyoming, I always loved going to powwows. As I began to understand my own artwork, I realize now the powwow's impact on my works. When I was in graduate school, I began to focus on her image and family stories and translate that into my work, which led to my thesis, and an exhibition titled: It is the not knowing that burns my soul. I created works based on family stories and folklore. One story that has always stuck with me was that she would not allow her darker-skinned son to walk down the street with her in Alabama, fearing that he would be lynched. Although the primary medium was intaglio, I would often incorporate hair pics and hair in the pieces because my aunt told me how much she loved to comb her hair, but also she was very mean. Because of my great grandmother, I started printing on feathers to acknowledge my African, native, and African American ancestry.

HG: How did your work begin to focus on activism?

AJ: Activism has been in my family as long as I can remember. My father spearheaded the movement to make Martin Luther King day a holiday in Wyoming before it became a national holiday. Since 2015 my art has steered more towards activism. A great friend told me to "use your art as your activism." 2014-2015 was extremely significant because of Philando Castille, Tamir Rice, Eric Gardner, and the killing of unarmed black folks by law enforcement. But Sandra Bland was close to home. Sandra Bland was home. The route that I drive to school daily, I pass where she was arrested daily. The fear of driving to campus the first day after her death was very, very unsettling. I was actually in Tougaloo, Mississippi, when I heard about what happened to her. I started doing a series of sunglasses called 'You Can't See What I Can See,' in response to the decisions made not to charge law enforcement for these killings. We see these acts of violence on tv, but apparently, we are not seeing what we're seeing because these officers are rarely charged or convicted. The first pair of sun sunglasses I created was titled: It Just Keeps Happening", which is a transfer print of a mother grieving her son. I also curated an exhibition that focused on women and brutality called "How do I Say Her Name." Women are not talked about enough. As I write this, unfortunately, it's the same song. Breonna Taylor was shot to death in her own home in her own bed. No charges.

HG: The lack of accountability on the part of the police in the murder of Breonna Taylor is systemic, historic, and tragic. We need BIPOC and white leaders to change the laws that govern police and accountability. As I read your words, it reminds me of the glasses you made a while ago and that they, unfortunately, continue to be relevant today. What brings you joy in these crazy days of 2020?

AJ: 2020 has been tough. WE MUST VOTE.

I never thought any year could be worse than 2016, but 2020 has been unbelievable. I lost my brother in February, and a week or so later, I lost my nephew at the hands of law enforcement. A week later, we were locked down. I thank God that I did not lose my job and maintained my position as an Art Professor. A day without a Zoom meeting would be wonderful! Lol. My family has not lost anyone to the virus, so I am very thankful for that. I am embracing the time to create and to focus on myself mentally and physically. My mother, at 83, has an interest in technology (Zoom, Google), which is very joyful, but when she joined Facebook, I had to get rid of a few FaceBook friends. ;-)

HG: Your printing process on vegetables is gorgeous, and I'd like to hear more about the process and the idea behind using that substrate.

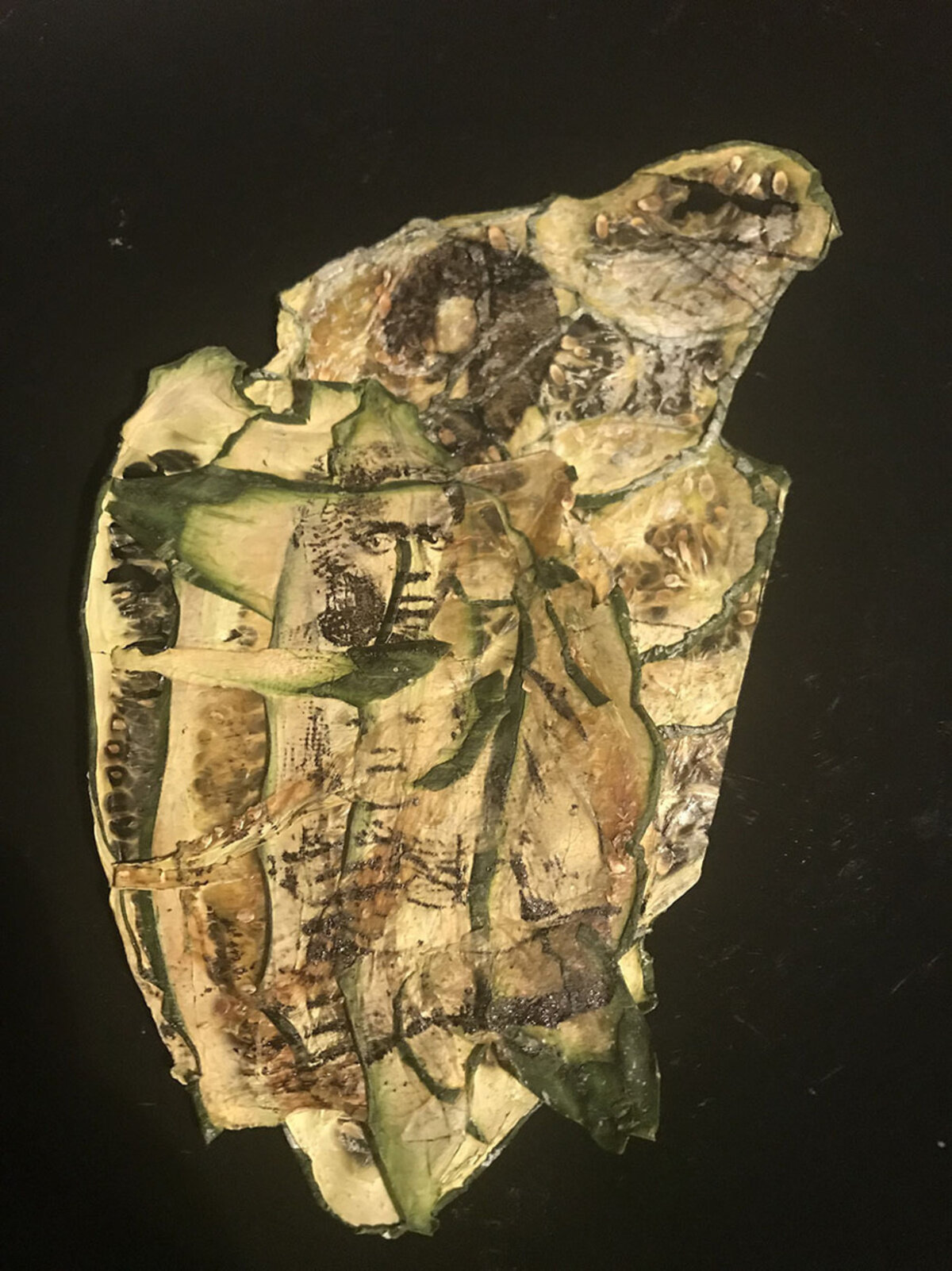

AJ: I am in an artist collective called ROUX. We have an exhibition every other year with PrintHouston. STIR was our second exhibition, and I mimicked a conceptual version of my grandmother's kitchen. This was when I began experimenting with vegetable paper, using dehydrated vegetables. I discovered that zucchini, squash, and cucumbers make incredible prints, although they don't last long. However, sweet potato and yam prints seem to last forever, which is interesting as the yam was a crop brought to the U.S. from Africa. Once the vegetables have been dehydrated after about 6 hours in the dehydrator, I organize the pieces and print them in the intaglio technique. The yams are less fragile than the zucchini and other prints. They are very sturdy and can stand on their own. The visual creates a range of narratives and conversations.

ROUX COLLECTIVE

ROUX [ROO} A mixture of flour and fat that, after being slowly cooked over low heat, is used to thicken mixtures such as soups and sauces. This dark nutty-flavored base is indispensable for specialties like GUMBO, ETOUFFEE, and BECHAMEL.

In 2011 the artist collective ROUX was formed as part of the inaugural exhibition series PrintHouston. ROUX contributes to the discourse of contemporary printmaking by using traditional and experimental methods while highlighting the diverse art practices of Rabéa Ballin (@rballin), Ann Johnson (@solesisterart), Delita Martin (@blackboxpress), and Lovie Olivia (@lovieolivia). These four artists' works navigate between styles of the past and the proposed future while addressing experiences unique to Women of Color residing in the American South.

HG: Thank you for the interview and sharing your work.

AJ: Thank you!

All images © 2020 Ann Johnson