Q&A: Amy reidel

By Jess T. Dugan | January 6, 2022

Amy Reidel is a St. Louis-based artist who has exhibited work regionally and nationally. She has been a resident artist at ACRE (Artists' Cooperative Residency and Exhibitions) based out of Chicago, the David and Julia White Artists’ colony in Ciudad Colon, Costa Rica and at the Luminary Center for the Arts in St. Louis. She has exhibited work at venues including the Contemporary Art Museum-St. Louis, ACRE projects gallery in Chicago, and the Amarillo Museum of Art. Her work has been viewed online in the curated artist registries and viewing programs at White Columns and the Drawing Center in New York City. In 2014, 2019 and 2020 Reidel was awarded Artists’ Support and COVID-19 relief grants from the Regional Arts Commission of St. Louis and the Washington University/Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum. In 2016 she received the Critical Mass Creative Stimulus award. Reidel is currently a faculty member at Washington University and St. Louis Community College as well as Co-Founder of All the Art: The Visual Art Quarterly of St. Louis (2015-2020).

Jess T. Dugan: Hello Amy! Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today. To begin, could you tell me a bit about your background? How did you initially discover artmaking, and what was your path that got you to where you are today?

Amy Reidel: Hi Jess! Thank you so much for inviting me to be interviewed and for the interest in my story and my work. I was raised in St. Louis, Missouri by my very devoted and hard-working parents, and I developed a love of drawing and coloring rocks when I was 3 or 4 years old. I remember drawing for hours and hours while at daycare or preschool because I missed my mom and was painfully shy. Getting older led me to more advanced art projects and a love for the alchemy of mixing food ingredients and eye shadow colors, then eventually paint, pastels and other media.

High school was a rough time for me as I struggled with my sexuality and other issues. I was 15 when I tried to come out but my Catholic/Christian upbringing didn’t exactly jive with being a gay teenager, to say the least, and I faced rejection, bullying and depression. I don’t want to go on about this distress but it was devastating and formative in multiple ways. During that entire time, I was supported in my art-making by my high school art teacher. I made intense, emo drawings and paintings which are embarrassing to think about now but which surely saved me. I began identifying very early on as an Artist. Somehow, life led me to my partner Rick, who embraces me fully as the queer gal and artist-mother I am now. It’s taken me about 20 years to say those words to people beyond my immediate circle so thank you for the opportunity to disclose something so important.

More linearly, I went to community college and then to the University of Missouri-St. Louis where I first majored in psychology and minored in art. As my last needed art credit approached I changed my major to Studio Art. I graduated with a BFA and then Rick and I followed our dreams to the American Southwest, where we were caretakers on a vineyard and small ranch in Abiquiu, New Mexico (where Georgia O’Keefe had lived). We worked for the property owners and tended to 62 acres of alfalfa, baby grapevines, a fruit orchard, vegetable gardens and ten chickens. After realizing I needed more education to be the artist I wanted to be, we moved to Knoxville where I got my MFA at the University of Tennessee. While in school, I attended a month-long artist residency in Costa Rica, had my first solo shows, and worked with many mentors, professors and friends who have had a lasting impact on me. I moved home to St. Louis in 2010 and have been teaching, gardening, spending time with family and making art ever since.

Sweet Jammy Nightmare (installation view)

Paintings, works on paper, mural, ceramic sculptures, glitter rug, 2019

Background Mural: Vera’s Marks, 11’ x 23’, Latex paint

JTD: That’s wonderful- thank you for sharing so much about the personal side of your journey. When writing about your work, you say you “use abstract and figurative imagery to illuminate the bittersweet conditions of caregiving, relationships, and sexuality.” Could you expand on this idea? How would you articulate the core ideas that motivate your work?

AR: Absolutely. While I was in school, and otherwise in the early- to mid-2000’s, there was still a dated, modernist, misogynist art world dynamic that I totally rejected at first but after years of exposure began buying into. These were my trusted mentors, after all, and this was the Art World in which I so badly wanted to participate. I was often told my work was a little too emotional. Or voyeuristic. Or Personal (Gasp!). It was “crafty” or “not archival enough.” I began to latch onto other visual languages to say what I wanted to say. After learning more about the work of two of my favorite artists, Felix Gonzales-Torres and Louise Bourgeois, and their use of more minimal symbolism to portray autobiography, I began using weather radar imagery as a metaphor for my own personal narrative. With this abstraction I made work I was very proud of while also dutifully satisfying the criteria of not being too…crafty? Female? Emotional? My most recent weather radar installation was in 2017, well after I rejected the misogyny I had accidentally internalized and I still think it’s good work. But it also felt slightly fabricated. Maybe just a little too clever. It didn’t always feel completely true.

TumorStorm

Loose glitter and colored sand on vinyl

Approx. 7' in diameter, 2016

Photo: David Johnson Photography

After experiencing the effects of pregnancy and a childbirth that did not go as I had planned (grateful we all came out alive and well), after watching multiple family members including my mother quietly go through life-threatening or terminal medical issues, and during the #metoo movement, I re-gained the courage to make work more obviously inspired by typically “unprofessional” issues. Themes of caregiving, the messy beauty of loving another person, and the disconnect between perceived and actual identity of women and mothers became my muses. My truest language to say what needs to be said even if it doesn’t universally apply to the art world gatekeepers.

I have found that these seemingly personal themes are actually quite global. They’ve just been the silenced perspective of women for generations.

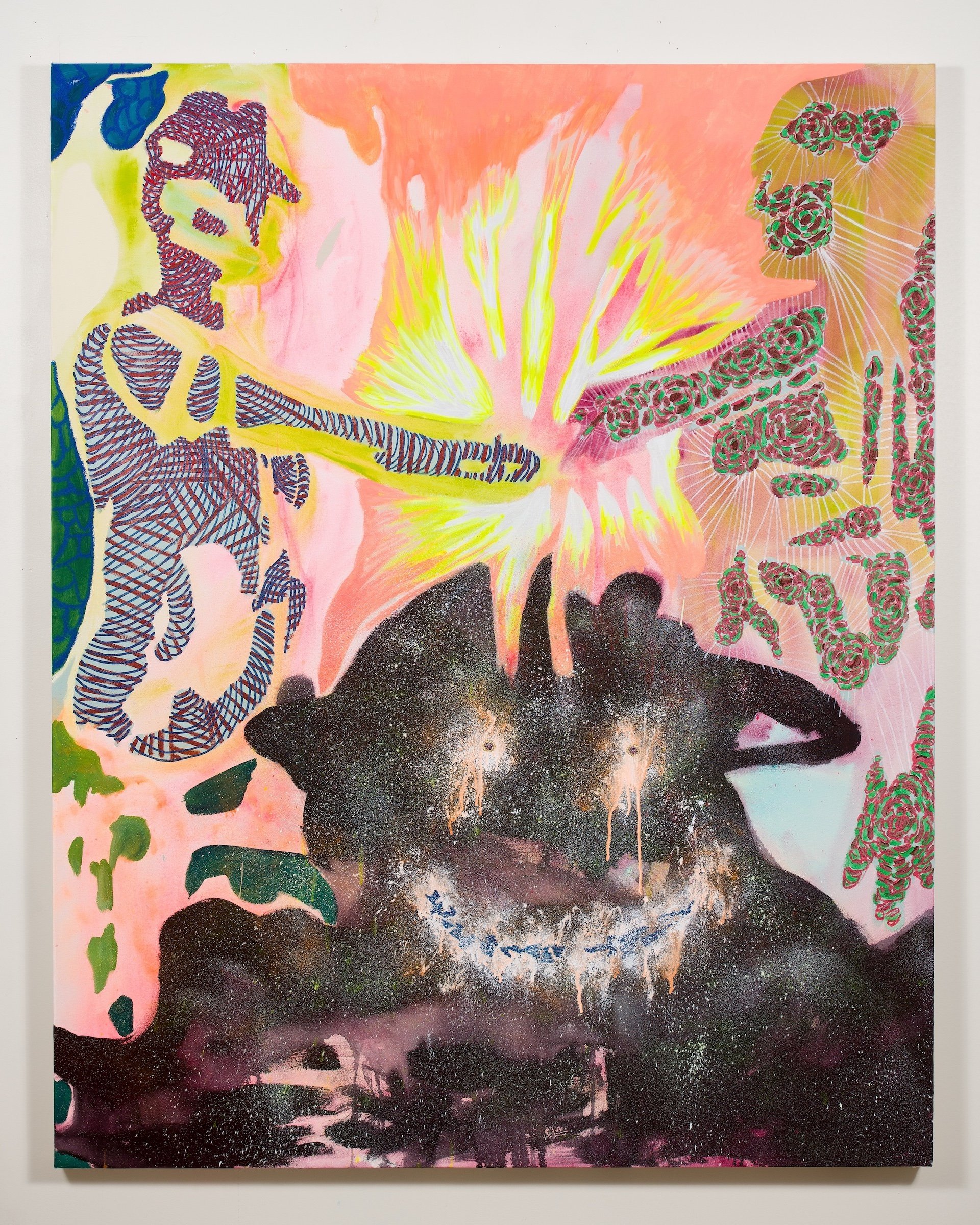

Jammy Nightmare

Acrylic, glitter, oil, spray paint on canvas

60” x 48”, 2019

JTD: Absolutely. Let’s talk about media for a moment. You work in painting, drawing, sculpture, and installation, and you often incorporate less-conventional materials such as glitter, medical tape, and cut paper. Can you elaborate on your choice of media and materials? What informs this choice, and how does it manifest during your creative process?

AR: This is such an important question that I consider so seriously even as I’m squeezing out cheap acrylics from JoAnn’s on to my ceramic sculptures and adding glittered fingernail decals from the dollar store to my drawings. To put it bluntly: I am a first-generation college graduate and I come from a working Midwestern family. My beloved wedding cookbook, derived from family recipes, has a meatloaf chapter. My Grandma married a wealthier man later in life and wore a 4-carat diamond ring but drank Bud Light out of a can. That’s basically the equivalent of “oil on canvas” vs. “glitter” to me. High vs. Low. Although many of my tastes are different from my family, I love these qualities. I want to pay homage to where I come from and my experiences. I’m compelled to re-claim the craft materials of my life and the women that came before me. Sourcing these unconventional media and combining them as an academically trained painter feels like a fair contribution to the canon. Or a version of the canon I wish to create.

During my creative process, I rotate between the disciplines frequently. Painting is very difficult for me compared to works on paper and the ceramic sculptures. Drawing is my primary language, and the most comfortable for me, so that is where I begin with a new body of work or after a studio hiatus. Moving materials around on low-stakes paper frees me up to grow my body of work in an experimental way.

The Mombie Series (partial group)

Acrylic, oil, glitter, spray paint on glazed stoneware

Dimensions vary, 2021

JTD: Let’s double down on your process. What does a day in the studio look like for you?

AR: I have a private studio out of the home in a building with about 23 other artists, a ceramics studio, kitchen and more. Before I became a mother, and a bit after, I worked in our home basement. It was great and convenient especially when I was nursing and my daughter wasn’t yet mobile. But now that she’s a preschooler, it’s a different story. It is much better for me and our family if I have a place to go to work. When I arrive, I stare at everything for a little while, not as long as I used to, and I try to have a task prepared from the last session so I don’t get too lost in my head. If I have a painting (or 2-3) in progress, I get right to work on that or I sit at my desk or on the floor and continue with some works on paper or head to the ceramics studio to create some of my Mombie sculptures. Recently, I completed a couple of paintings after months in progress and it was so invigorating to work on them. As I mentioned, paintings are difficult for me, but these latest works finally clicked after many clumsy stumbles. Unfortunately, finishing those works aligned with the holiday season and a sick 4-year-old so I’ve had an extensive break from the studio and will soon go back to blank canvases. Yikes.

JTD: What is your process for going from an initial idea to a finished piece? What is your process for making a body of work over a longer period of time?

AR: There are times when it all feels quite organic or intuitive and I appreciate the sort of spirituality associated with those terms. But I’m also a trained artist so my process isn’t accidental and is informed by history, technique and the principles and elements of design. Even if it feels like second nature to me, or almost reflexive at times, I trust it’s quite cerebral as well. Considering my bodies of work, I think in terms of exhibitions, not in individual artworks, so diving in with just one work from start to finish is very, very rare for me and uncomfortable. I love working with the breadth, positioning the different media together, initiating a conversation with each other in a space and with my audience.

To be specific about the physical process, with my paintings, I begin with a layer of water-based paint like watercolor or diluted acrylic. I create pools and stains, with the surface lying flat on the ground. Usually there is a vague image of a caregiving mother-type figure, a baby or empty arms, multiple faces, a couple/pair reaching for each other, or a rug/scarf design. After it’s dry, the layering and abstraction begin. A painting takes me months to complete and it’s a struggle almost the entire time. In the end, though, the heaviness of pattern, color, layers and hints of figures are really satisfying for me. Works on paper begin the exact same way with watercolor washes and wet on wet painting. Then I add collage, pastel, woodless graphite pencils, charcoal, tape, glitter glue, and marker. I work on a layer a session, always careful to leave the works on paper in a good state to come back to for my next studio day. I begin about four at a time, around 11 x 15” approximately. While these layers are drying or when I’m stuck on what to do next with my paintings and drawings, I weave little rag rugs for my Mombies and hand-build or glaze my ceramic works. All the while I am considering installation possibilities or plotting the next glitter rug. My brain is pulled in about five different material directions at once and I’ve been operating like that for a long time.

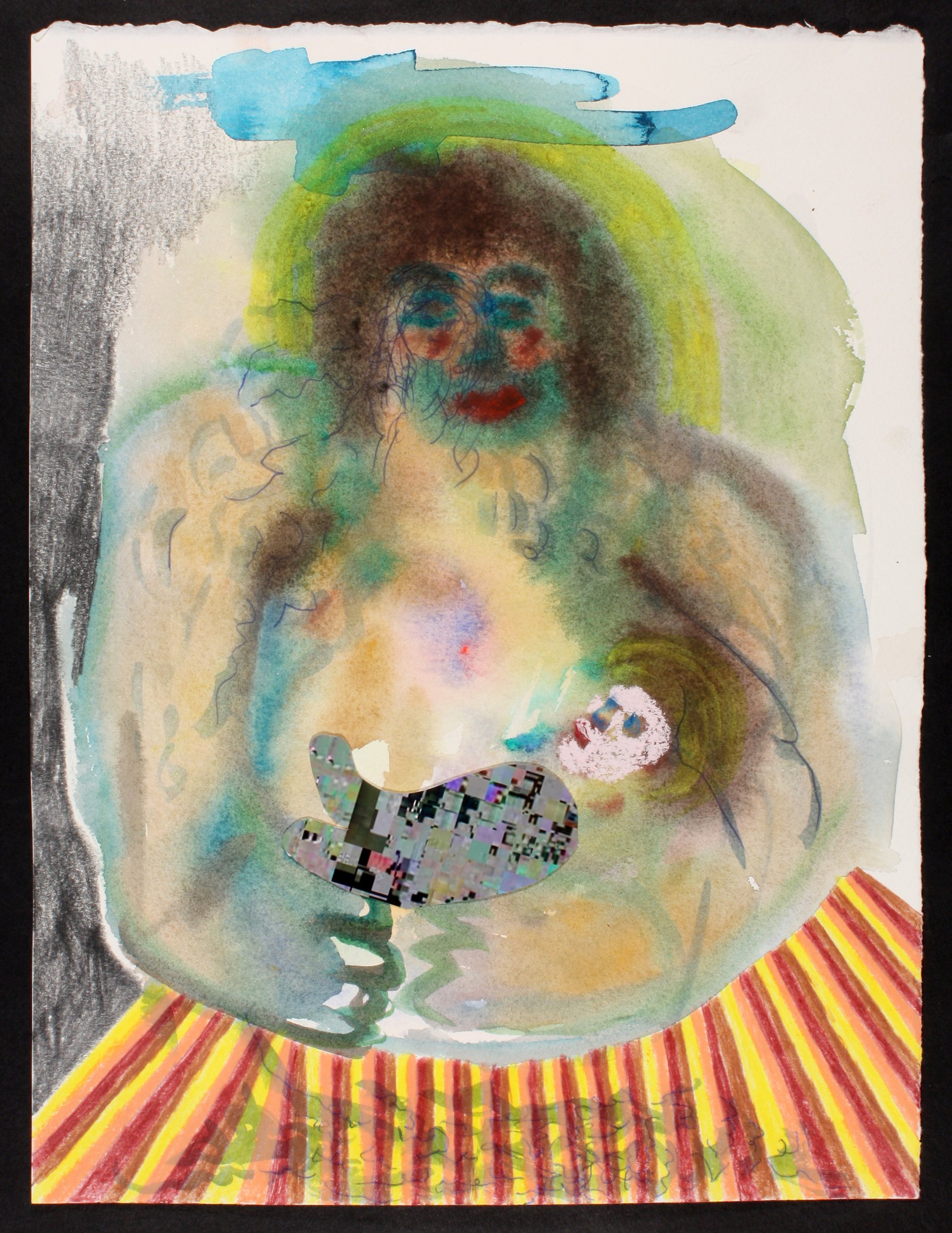

Birthday Queen

Mixed media on paper

13” x 8”, 2018

JTD: Your work is highly personal, and also explores ideas that are, as you write, both “commonplace and clandestine.” To what extent do you process your own life and experiences through your work?

AR: I am often told how personal my work is and although I obviously recognize this, every time it leaves me a bit puzzled because it seems that most artists use autobiography as an impetus for their art practice. So I often wonder what makes it worth mentioning with mine? Although I do feel that the withholding of personal narrative and struggle perpetuates certain ideas of “professionalism” that I’m not interested in, I am also conflicted with, of course, wanting to be taken just as seriously.

Even though art is not quite therapy for me, I do absolutely source some imagery from my own fears and experiences. My recent paintings and drawings might appear to be exclusively about mothers, but I am most interested in reflecting the human condition and the joys and anxieties that afflict us all. As my friend, wonderful artist and curator Jennifer Seas says, “if you have a body, then you have/had a mother.” It’s really not very subjective content at all.

Additionally, most of my work is more of a response to the news of the world. As a woman with white privilege but not excessive financial privilege, I often struggle with what I can contribute. When the news broke of the family separations at the Mexican border, like many, I was appalled. Sickened, thinking of those children in cages without their parents. Thus, the Mombies were born. My small army of ceramic caregiving sculptures attempting to save the world through a matriarchal revolution.

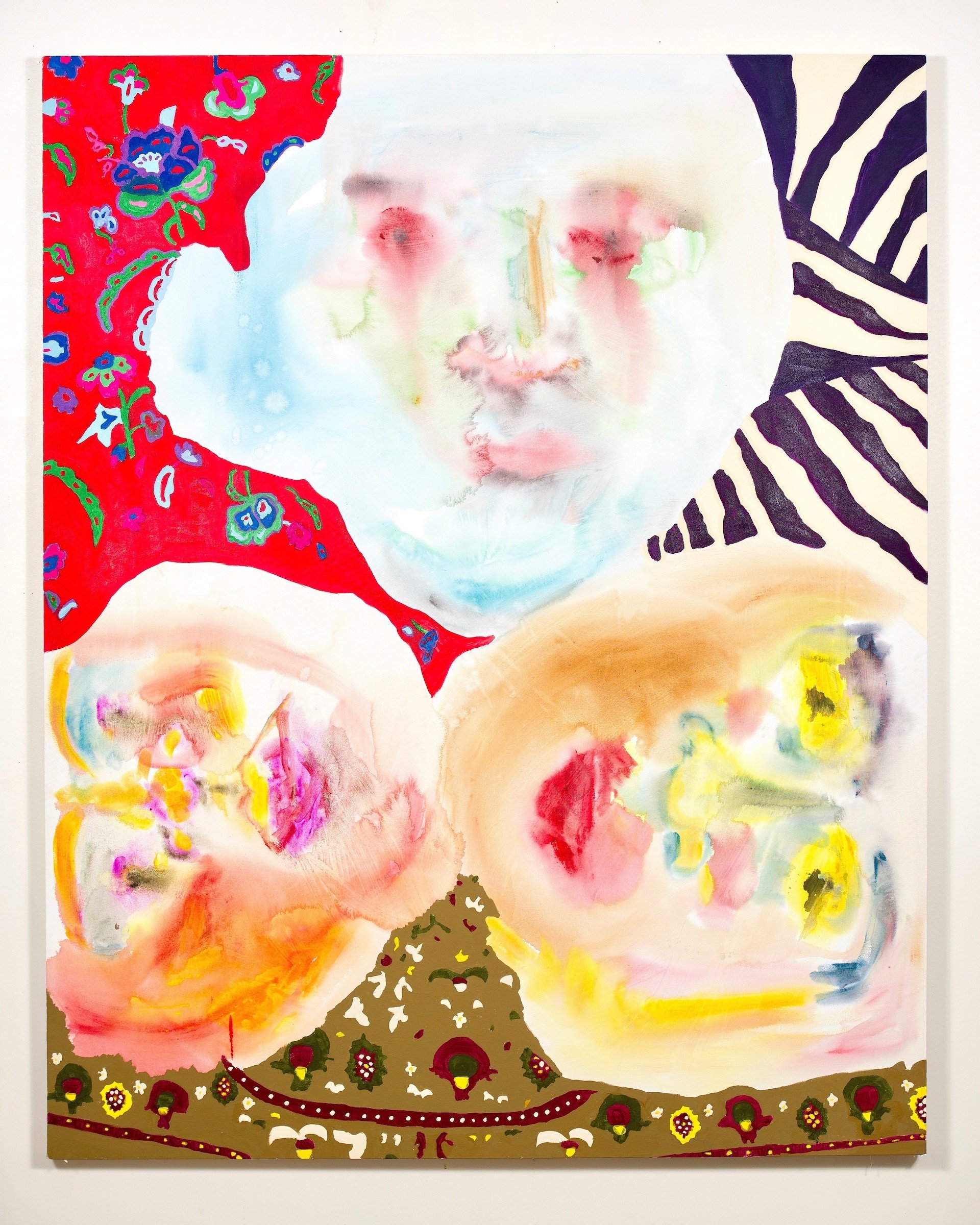

Mommy Sphinx

Acrylic, fabric paint, glitter glue on canvas

60” x 48”

2019

JTD: Much of your work focuses on ideas of motherhood, sexuality, and women’s health. These topics, of course, have not always been readily accepted as serious work within the art world (in your artist statement, you reference L.H. Baggesen’s concept of the “mother-shaped hole” within art history). How has your work been received? Do you feel that you’ve encountered barriers to having your work exhibited, collected, or written about because of its subject matter?

AR: This is such a powerful question and one that needs to be addressed on a much broader level beyond just my own work and career. I can’t be sure about the answer because if an entity openly rejected my work due to the subject matter that would be akin to gender discrimination. So I don’t think we’ll ever really know how many careers or artists have been stifled because of the status quo. I certainly do suspect, however, that my work has been looked over, rejected, not reviewed, or not collected by some parties for that reason. If I look at the award winners of competitions and major exhibitions just here in St. Louis, it’s quite easy to see that gaping hole in representation. Occasionally, an artist-mother is the recipient but rarely is the work explicitly about those related issues. So my short answer is yes, and I am far from alone in that regard. Unfortunately. Even though I feel my career has been possibly stifled, either due to my location, my gender, subject matter, or my actual caregiving roles, I still have seen great successes thanks to some courageous and feminist curators, advocates, directors and collectors. I am so very grateful for their faith and interest in my work and I hope to pay that faith forward as my career progresses.

JTD: It seems that there is significant traction within certain parts of the art world to make opportunities, such as residencies, more accessible to artists with caregiving responsibilities (in particular, those who are parents, although I have seen some institutions supporting caregivers more broadly). Do you perceive this shift? What are your thoughts about the current state of things for artists who are also parents?

AR: I do see that shift happening thanks to organizations like the Sustainable Arts Foundation which focuses all support on either artist-parents or ensuring that artist residencies accommodate artist-parents. A few recent exhibitions here and there have popped up which seem to focus on motherhood and parenthood. And although these are big strides in improving accessibility for artist parents it is still not fixing the system. Caregivers in general are still not well supported in the art world, or any world for that matter. To be clear, in my work and in my life, I use the term caregiver more broadly than parenting or mothering, having grown up helping my family care for my uncle with muscular dystrophy. I’ve seen what devoted caregiving can do when a disability is in the picture and also when it’s related to parenting or caring for an aging parent. I think often about some artist friends (myself included) who in no way could attend any residency because their parent or partner is sick. There are more residencies and opportunities for caregiver-artists than there were just four years ago when I became a parent. They do seem to be mostly less-established, or alternative spaces or exhibitions, but they are moving the dial forward which is terrific! It’s still fairly defeating, though, to read through the FAQ’s from a stalwart of an organization and see that ‘NO, a dependent or partner is not allowed to remain overnight…’ That immediately rules me out. And many others as well, I would think. Even before having a child, I noticed how inaccessible those regulations make it for many populations. As though growing a network, developing work and gaining opportunities is reserved for a VERY specific demographic. That sure enforces an idea of what a “professional artist” looks like and that’s not a system I’d like to participate in. Unfortunately, there aren’t many other safety nets or systems set in place yet for artists.

JTD: What are you currently working on, and what’s on the horizon for you?

AR: Well, after some tough rejections and questioning my content and more, I had a brief moment of considering moving on from my current practice and subject matter. Thankfully, after a few weeks of sulking, talking with trusted friends and digging deep, I decided instead to double down. Which is so liberating! I recently finished a painting I feel so proud of which is like some kind of 2021coviddumpsterfiremotherchildMaryCassatt piece. It’s my current favorite and I look forward to exhibiting it in 2022 at the High Low Gallery in the Kranzberg Art Center in St. Louis. I’ll also be participating in a group show at projects + gallery in January and a solo show at Beco Gallery in Kansas City in March. I’m eager to expand beyond the St. Louis area and will focus on that for 2022 and 2023! Maybe even attend a family residency if I’m lucky.

JTD: Wonderful, thanks so much Amy!

All images © Amy Reidel