Q&A: Alessandra Torres

By Rafael Soldi | December 8, 2016

Alessandra Torres was raised in Puerto Rico. She received a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) in 2002, and a Master of Fine Arts in Sculpture at Virginia Commonwealth University in 2006 on a Jacob K Javits Memorial Fellowship. Torres’s performances, installations, and photographs have been exhibited nationally: in Washington D.C., Los Angeles, New York City, and throughout the Mid-Atlantic area, and internationally: in Holland, London, and most recently in Bilbao, Spain for her first international solo exhibition at BilbaoArte. She has participated in such prestigious residencies as The Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Sculpture Space, Vermont Studio Center, The Prague Summer Theatre Program, and The Creative Alliance. Alessandra currently resides in Baltimore, Maryland where she serves as an Adjunct Sculpture Instructor & Undergraduate Admission Counselor, for national and international recruitment, at MICA.

Rafael Soldi: Your work is roughly divided into photography, performance, and sculpture/installation. Can you describe what role each of these mediums play in your practice?

Alessandra Torres: Photography serves to captures intimate, private moments of transformation and connection - when my body merges with its surroundings; the moment when a dance or movement becomes a drawing; the magical instant when the figure becomes a character in a fairytale. I have always used my own body in my photo work, so the photographs allow me to witness my physical impulse from the perspective of the viewer. I know the photograph is a success when it teaches/shows me something more advanced that I could have imagined. I direct every shot: the angle that it’s taken from, the composition, the lighting… Most importantly, in the photo work, my face is almost always turned away from the camera in order to allow the viewer to psychologically enter the work – so that they don’t have eyes staring back at them making them self-conscious, breaking the fragile and fleeting suspension of disbelief. The goal of my photography work is for the viewer to connect with my body, to empathize with what my body is doing in the image and to imagine it as their own.

My live performances are extremely rare occurrences; years may pass between my live body events. I prefer not to refer to them as performances, but instead something more akin to “physical interactions”. My body is present but I am not the focus, the real focus is the viewers’ response and how, or whether, they choose to interact with me, or not. The goal of my live body work is to activate the viewer, to make them conscious of the fact that they are a living breathing physical being in space, to allow them to connect directly with my body, and to, ideally, and ultimately inspire empathy. Like in my photography work, my face/eyes are often covered. This allows the viewer to stare, to come in closer, and to touch me without eyes looking back at them. There is only one instance where I am looking back at the viewer during one of my live body events, and that was because the goal of the piece was to consciously threaten, and aggressively invade, their personal space.

Personal Space Experiment

In graduate school in VCU’s MFA Sculpture Program, my teachers challenged me to make work about body, without my body being present. That was the inspiration for my Interactive Sculptural Installations. The viewer’s body became the focus of the work – I realized that the body interacting with the artwork should be that of the viewer, if the goal was to activate them. My Interactive Sculptural Installations encourage the viewer to experience, learn, and communicate through the body - activating and empowering them through the accomplishment of a physical feat.

RS: In your work you play with scale, whether it is by enlarging your body digitally, or placing your body in spaces that seem dwarfed by it—in a field of tiny hills, in an adult-sized incubator, surrounded by a tiny brick wall, or your body as a mountain. Conversely, many of your sculptures are larger-than-life replicas of very small things (i.e. spinning tops). How does this shift in scale help you explore your own identity?

AT: Shifting scale creates a whole body sensation - manipulating, transforming and affecting our sense of self in relation to our surroundings. Creating something large dwarfs the body, making it vulnerable. Shrinking something in an artwork empowers the viewer… I explore the power of scale in order to portray my psychological sense of body, versus how others’ view might see me. My sense of body and self is very abstract. It is constantly shifting and evolving, so documenting through my artwork, my interactions with the world around me help me to take control and solidify my identity.

Adollsessence

My interest in the power of shifting scale originated with images from a photo shoot during my sophomore year in MICA’s Undergraduate Sculpture Department. I was using photography to document my interactions with a large plaster doll head that I had made for a masks and headdresses class, inspired by a miniature plaster bust of a young adolescent girl that I had purchased in the basement of an old, dusty, doll store in San Sebastián, Spain. I reproduced this head keeping the doll’s same proportion in relation to my own body, and as a result the plaster head dwarfed my body – transforming me into a giant child. This was the first sculpture I had ever made that I felt compelled to interact with physically. I needed to physically inhabit/wear this large doll head in order to figure out what fascinated me so much about it. I photographed myself, nude and wearing the head, running into the dark train tunnel. When I got the images back, there was one that I thought was an image of a tiny doll, when in fact it was me wearing the plaster head. I felt the scale shift happen in my body, looking at this image and then realizing what it was - thinking initially that it was a tiny doll, then realizing that it was a whole human being. I continued exploring the effects of shifting scale, through my series of photographs, “Shadow Drawing” – documenting myself dancing wearing a 60’ long black skirt, photographed from about 30’ in the air. The resulting images look like sumi ink paintings, and as a viewer you approach them as such, only to have them explode to their enormously large scale once you’ve recognized the tiny figure at the beginning of the long curving black mark. I always carefully consider the size of every element in my artwork, how it will contribute to the concept of the piece, and on the viewer’s response.

Shelter

RS: You often use the pseudonym is Play Pretend, which I find very fitting. Your work is often playful—childlike, while not childish. You test to see whether your body fits into drawers and chests; you pretend you are the person who makes it snow; you turn yourself into a spinning top. At first glance there is a naïveté and simplicity in your approach that is often found in child's play, but a closer look reveals a certain heaviness—a deep physical and emotional negotiation with your own body, experiences, childhood, and surroundings. Do you consciously gravitate towards playfulness to mask some of the darker elements of your work (or perhaps, to enhance it), or is this somewhat unconscious?

AT: Art-making makes visible and tangible the current of emotions, feelings, impulses, reactions, and responses that course through my mind and body as I move through this world, exploring my surroundings, and interacting with others. Children are free to release, express, and explore through the multi-sensorial experience of play. But, “play” is not something that we are encouraged to do, or often given the opportunity to do, as adults. As adults there is very little time or importance given to play. I remember during my sophomore year in college, my professor encouraging us to “play”: to act on impulse, to make art on the spot without time to prepare or research, to make art with “nothing” but what was around us in the immediate situation. To be present, to listen to our responses, and reactions, as well as to pay attention to the things that we were drawn to, or repulsed by - to explore all of that, reflect on it, and build from there - and to trust that the result would reveal infinite insight. (And it always has.) We were also encouraged to reflect back on our childhood, to remember games that we enjoyed playing, actions we repeated, sensations we liked and/or disliked - and this proved to be the most helpful exercise. I learned that I prefer to experience the world around me with my whole body. From the time I was small, I loved physical sensations: of hiding, squeezing into that tiny space between the back of the couch and the wall, cramming myself into my parents’ clothes hamper - the charge of being simultaneously present, yet invisible. I binge watched horror movies, because I loved that those images on the flat 2-dimensional television screen could completely electrify my entire body, activating all of my senses. I craved that whole body sensation. I also rearranged the furniture in my bedroom regularly as a child, because I loved the sensation of being disoriented. I loved waking up, and that moment when the imagined layout of the room in my head would suddenly shift, spins, and readjust to the newly arranged reality of the room around me.

I do not come from a background that is well versed in contemporary art, but I want my family to be able connect with what I am making. I want my viewer to feel empowered by my work. I want them to say: Oh, yes, I’ve totally had that impulse - I share that desire to climb/hide/collide. I want to encourage them to pay special attention to that - to listen to that reaction. Play is important because it reveals inner truths. My goal as an artist is to generate wonder in my viewer, to get them to see something for the first time again, to encourage them to allow their body to lead, to play - and to pretend.

The Portable Winter Series: Snowfall

The Portable Winter Series: Snowfall

RS: I love this idea of using your body as a mark-making tool, as a measurement tool. Movement is such an important part of your work. Can you describe your dance machines and any other works in which movement is important?

AT: We understand everything with our bodies, employing all of the senses that we possess. We make art using our bodies. Art records, captures and displays a gesture. I am fascinated by the concept of an artist’s fulcrum of creation, the part of the body, and the gesture or movement, used to make an artwork. Some artists make with repetitive tiny fingertip movements, others with the whole arm. I think, and make, with my whole body. I began as a painter, and I felt so limited standing there in front of the canvas trying to communicate all of my feelings through these tiny brush marks. It wasn’t long before began covering myself in paint, pressing my entire body against paper, in search of a more genuine, more immediate self-portrait. My current artwork records and explores gestures as small as contorting my body in order to fit within the fireplace, or closet in my home, to gestures as grand as creating a seemingly-magical snowfall on a hillside, and as complex as the gyrations involved in a dance movement.

I define myself as a "body thinker". I learn through re-enacting something, by experiencing something with my body. When I enter a room I am hyper aware of its scale in relation to my body. I feel the freedom and excitement inspired by a large open space, the intimacy of a smaller room… I scan the room for hiding places…where do I fit, what could I crawl into, where could I hide? Art provides an outlet for this form of body thinking, and gives me the opportunity to spotlight spatial/kinesthetic and body memory intelligence through my art, to show that it is just as valid, important, and essential as our most revered form of intelligence: the intellect and academia.

My body is my tool of measurement for creating and displaying my artwork. Often, my sculptures are my body’s height and width, so that the viewer is not only approaching my artwork, but they are also relating to the size of my body.

My Instructional Dance Machines were inspired from growing up in Puerto Rico, where the body leads in dance, and in conversation and interactions with others. Puerto Ricans constantly touch one another in discussions, gesturing with the hands, shrugging with the nose, pointing with the lips and/or the chin. Even the way that people give directions is spatial and visual, no one knows the names of streets, which way is East or West, or the mileage it will take to get there – they will describe the entire visual and spatial experience of getting to the destination - using landmarks, the colors of buildings, how much time might pass to get there. And EVERYBODY dances there. Everybody. When new students from the USA arrived in Puerto Rico, we had to teach them how to dance. In fact, we created a sort of game in order to teach them to dance – and this is what inspired my most recent interactive sculptural installations, my four “Instructional Dance Machines”.

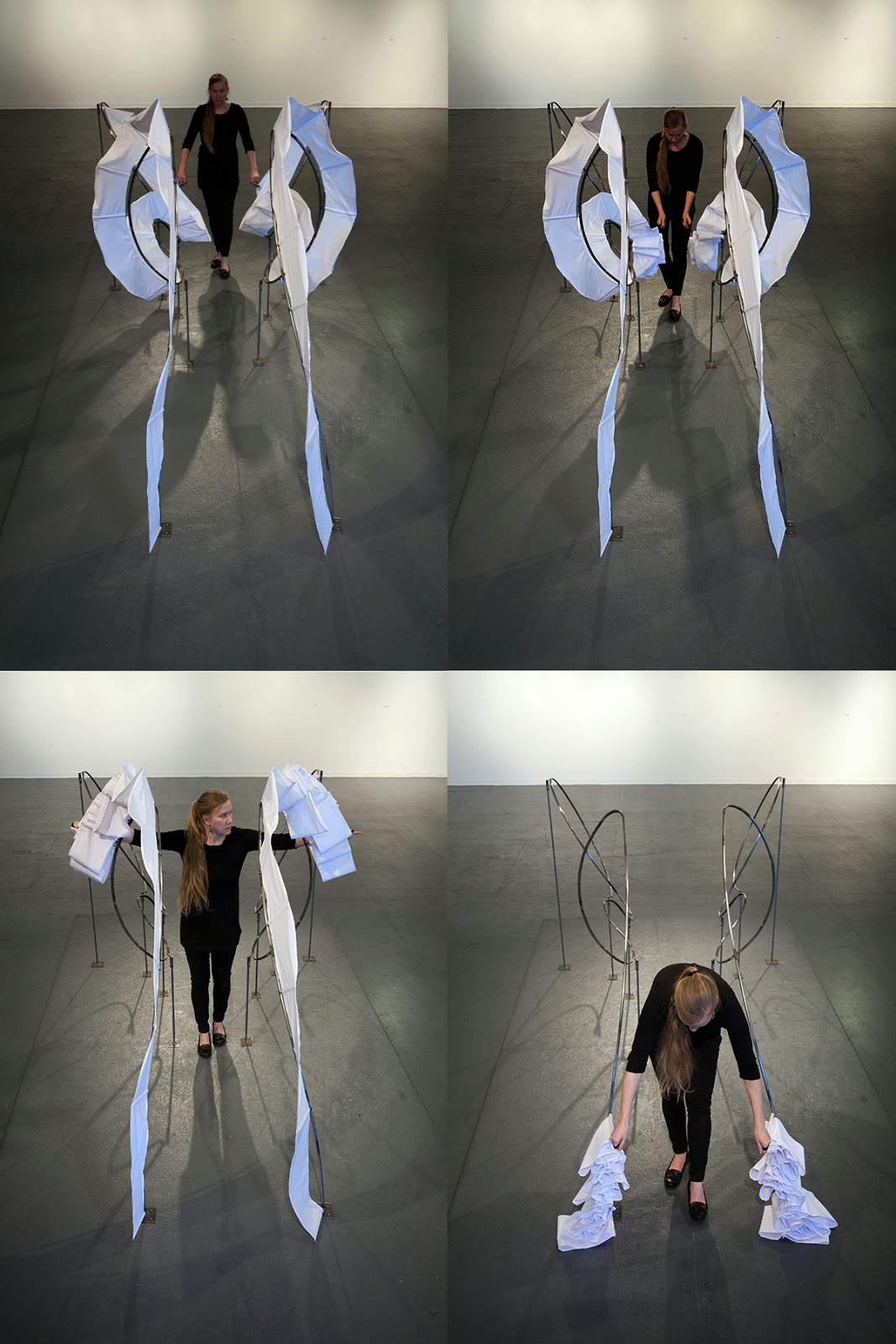

Instructional Dance Machine, Prototype #1

Interactive Sculpture where viewers "learn to dance" by holding on to the handles and sliding the fabric along the steel track. The dance move is an excerpt from “El Duelo” (The Wake), Flamenco.

Steel, Muslin

84” x 96” x 180”

2011-2014

RS: What have you gained from understanding your personal creative process?

AT: The creative process is different for every artist. For me, it is made up of my making process and my thought/idea generating process. And it is not linear. I see my creative progress/process as an upward spiral representing my growth, connecting with overlapping, vertical lines that are the themes/ideas. I notice that I’ll start something, and then revisit that idea again, or finish it, years later. My themes also overlap with one another, and sometimes there is that magical moment when one project answers all of the questions you were asking in a range of different projects. I got into so much trouble in grad school working this way: I’d be working on a sculpture of a figure, then at critique I’d present a series of photographs where I was making it snowfall on a hillside, then I’d make a piece where I was trying to learn to walk like a horse.

My brain is my sketchbook. I also like to think of my brain as a rock tumbler, full of hundreds of ideas rattling around, getting cleaned, and refined, taking shape until finally one of them tumbles out - a shiny luminous perfectly polished diamond. There is a lot of thinking that goes unseen, and undocumented, until the final piece is created. That is the most exhausting part.

Just like in sports, there is a learning curve to art-making. There is a similar fascinating, infuriating, mysterious relationship between our body and brain. As an artist, the most insightful and informative and empowering thing you can do is to understand both your making and your thought process. I learned that I have to take things apart, recreate them and put them back together in order to understand them. I learned this while I was busily re-inventing the wheel, doing something very easy the hard way – but it was the way that made sense to me. By understanding my thinking and making process I can ensure that the work is successful.

RS: You can trace a very powerful line from your work to some of the seminal women artists of the last five decades—tell us about the women you call "body thinkers."

AT: I’ve found other body thinkers working in a wide array of different mediums. The photographer Francesca Woodman - the way she interacted with her surroundings, her gestures, movements, and the compositions she created of her body in space. Ann Hamilton, who explores both tiny gestures, using her mouth as a pin-hole camera, and also giant gestures affecting the viewer. Her Art21 episode made me just want to throw in the towel – she’s just too good. There is simply nothing left to make after watching that. Janine Antoni is another. Marina Abramovic - her early work with Ulay was poetry. I love the way they represented their relationship and feelings toward one another with their bodies – facing each other, leaning back with a bow and arrow stretched taut between them, with the arrow pointed at the heart; sitting back to back with their hair twisted together into a bun; facing each other, naked in a doorway, waiting for the viewer to squeeze between them, connecting their bodies. The entire evolution of Rebecca Horn’s work: the way that over time she stepped out of the spotlight herself, to allow the viewer the full experience of the work. And, Cindy Sherman – there was an interview with her about her initial inspiration to dress-up as the “other”. She spoke about having this very abstract sense of self, that we could never see ourselves without the aid of a mirror, and how she longed to see herself as this complete, whole, physical entity like she saw others. So, she stood before a mirror with the camera set-up on a remote trigger, and she would dress up and look in the mirror, and wait for the moment when she no longer recognized herself – and that was the moment that she captured on film. Lucky for us she followed through with that impulse which led to her “Untitled Film Series”.

Although not an artist, Temple Grandin, and her book “Thinking in Pictures”, offers incredible insight into the thought process. She is a highly-functioning autistic woman, and she realized at a young age that the way that she experienced the world around her was much the same as how animals, specifically cattle, related to their surroundings. She could empathize with them, feel what they were feeling, and see the world through their eyes. As a result, she has gone on to become the designer of humane livestock hanging systems which are used all over the world.

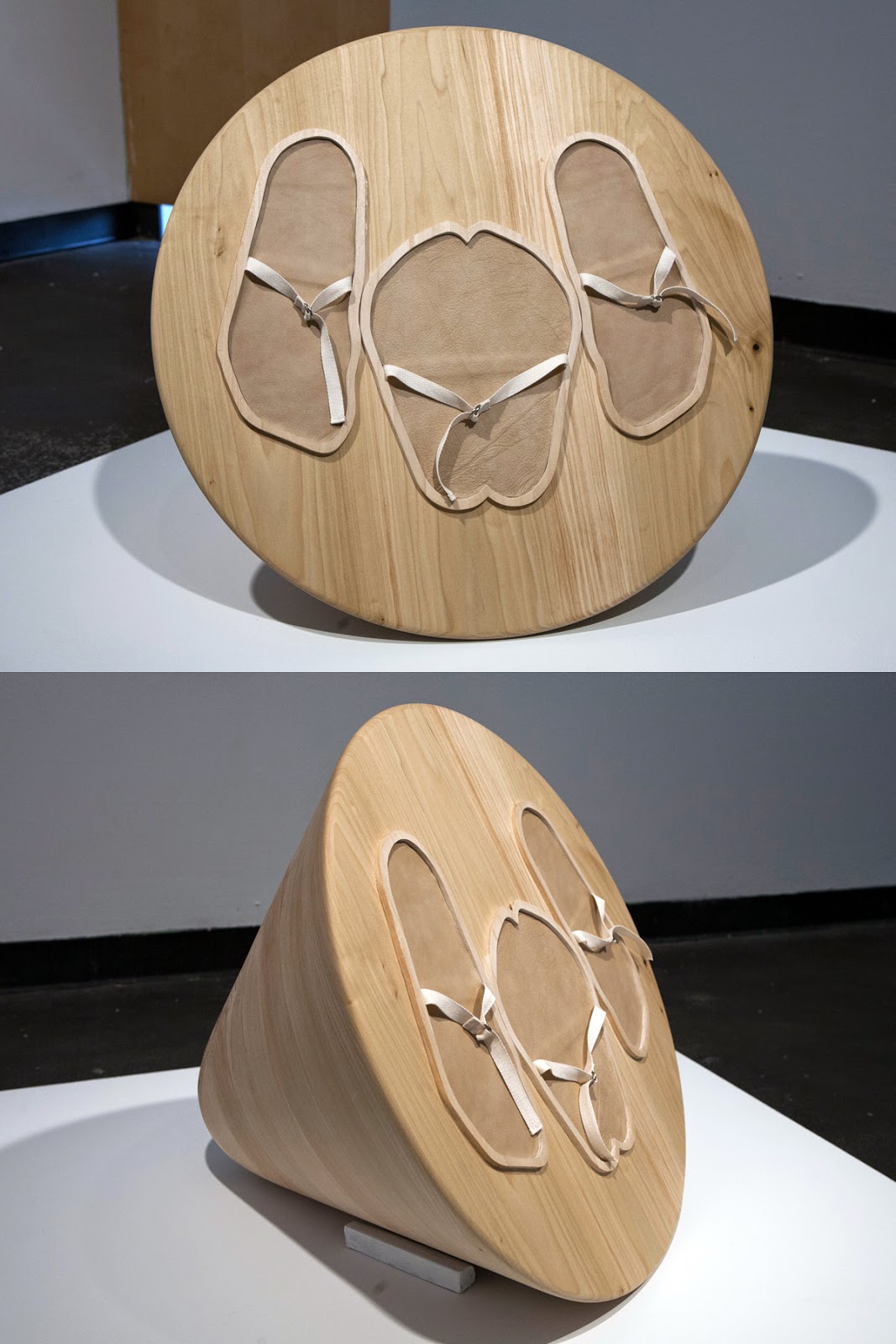

La Ria

RS: You just completed a 6-month residency at BilbaoArte, where you created extraordinary work. How was that experience, and what is next for you?

AT: It was a very difficult experience, mostly because it was an inconvenient time for me to leave the USA for 6 months. I was so uncertain that I would attend, that I didn’t get my VISA. So, once I arrived there I had to be granted permission to remain in Spain for the 6 moths, and I was not allowed to leave and return during that time. I got myself stuck there. Bilbao is a labyrinthine city, geographically located at the bottom of a bowl of mountains. Being there forced me to stay put, to focus, to make, to go to the studio every day. I didn’t take anything with me, so that I had to use only the materials I found there. My work documented my experience there, which was comforting, intimate, and confining. I was ultimately selected for a solo show which I entitled “Proprioception” and it took place in October 2015.

Currently, I reside in Baltimore, and am putting the finishing touches on a building that I have purchased. It has become my big giant artwork. It is a space that has helped other artists create work, and at the moment, I am helping to supply and create visuals for an immersive theatrical experience titled, “H.T. Darling’s Incredible Musaeum Presents: The Treasures of New Galapagos, Astonishing Acquisitions from the Perisphere” that will be taking place this Spring in Baltimore’s Peale Museum.

There are quite a few new artworks that are calling to me to make. I’m very interested in exploring other ways of recording movement in space. There is a photo series I’m working on - it’s a sort of cross between painting and a fashion show – it still has me completely baffled, which is a good thing. There is also a research project taking shape, perhaps for a PhD?!?!, exploring and researching how different cultures use, think about, and portray body. We will see. Please stay tuned.

All images © Alessandra Torres