Q&A: ADA TRILLO

By Hamidah Glasgow | October 31, 2019

Ada Trillo is a documentary photographer based in Philadelphia, PA, and Juarez, Mexico. Trillo holds degrees from the Istituto Marangoni in Milan and Drexel University in Philadelphia. Trillo’s work is concerned with human rights issues facing Latin American culture. Trillo has documented forced prostitution in Juarez, and the recent migrant caravan attempting to reach the U.S. Trillo has exhibited internationally at Saint Joseph’s University in Philadelphia, The Photo Meetings in Luxembourg, The Passion for Freedom Art Festival in London, Festival Internazionale di Fotografia in Cortona Italy and at the Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery at the John Jay College in New, York. In 2017, Trillo received a Leeway Foundation’s Art and Change Grant. Her work has been featured in The British Journal of Photography, The Guardian, and Smithsonian Magazine. Trillo was recently awarded a CFEVA Fellowship by The Center For Emerging Visual Artists and was named the Visual Artist-in-Residence for Fleisher Art Memorial in Philadelphia. Her work is included in the permanent collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

HG: Tell me about your history and why you got involved with the migrant/refugee/asylum seekers traveling through Mexico?

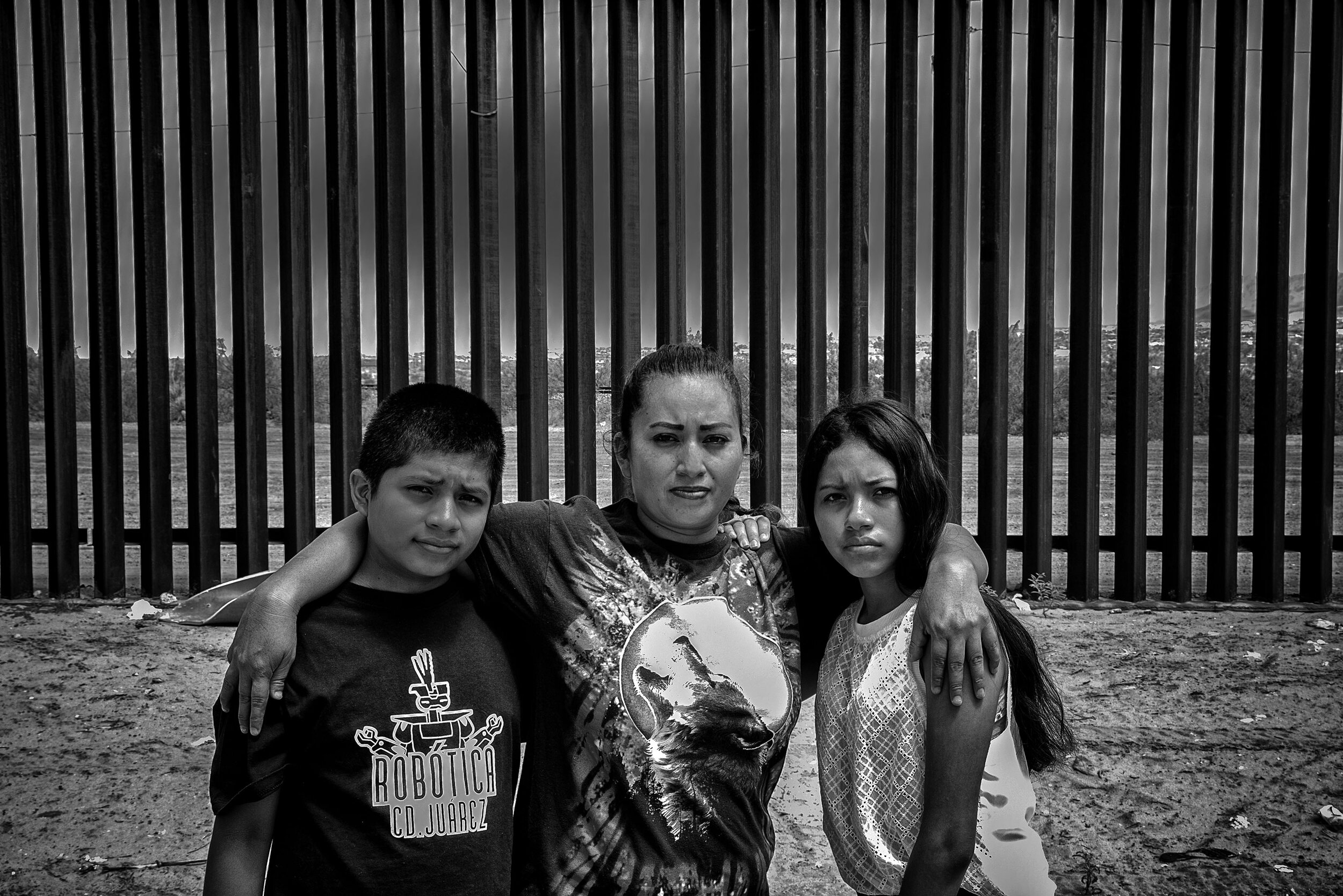

AT: The border is an issue that I'm personally tied to, but I'm also a woman, a single mother, and a member of the LGBTQ community. Naturally, my photography reflects what speaks to my heart. So I am drawn to the stories of those who are most vulnerable, the women, children, and members of the LGBTQ community who suffer through the travel and immigration process.

I was born in El Paso but raised in Juárez, Mexico. Because I'd been educated in the U.S., I crossed the US-Mexico border almost daily. I remember walking across the bridge that connects the sister cities and watching inflatable rafts fight the current of the Río Grande River below. Those lightweight vessels held migrants of the 1980s, desperately fleeing from crime, poverty, and political unrest. Today, as I walk across that same bridge, it feels as if I am watching history repeat itself.

In the summer of 2017, I flew to the city of Tapachula on the Border of Guatemala and Mexico. From there, I hopped on a bus to Arriaga Chiapas, a small village that serves as the first stop of the infamous La Bestia train system, which connects migrants to multiple cities along the U.S. Mexico border.

In 2019, I returned to my hometown of Juarez to complete a project about asylum seekers, having traveled back and forth to the border for the past three years. In those years, much has changed for individuals seeking asylum. The Trump administration has drastically cut the number of refugees that the United States will accept and is now requiring asylum seekers to remain in the first country where they land. As a result, many migrants are trapped in dangerous border towns along the U.S./Mexico border.

HG: Tell me about some of the people that you traveled with on your journey to the Mexican border?

AT: One of these people was, Kevin from Honduras, whom I befriended in Tapachula, and was hoping to get asylum in the United States. Kevin wanted to live a life free of the overbearing stigma that modern-day Latin American countries associated with the LGBTQ Community. I know personally the discrimination that exists against these people in Latin America.

Kevin eventually arrived at the U.S./Mexican Border and turned himself over to immigration, claiming asylum. Nobody has seen or heard from him since. I have tried repeatedly to get in touch with Kevin, and his brother in Honduras, a Priest, has heard nothing from him. Other transgender members of the Migrant Caravan are similarly escaping a life of prejudice and social torment, hoping to find acceptance in a more tolerant society. The stigma of their lives/choices is so deeply rooted in the Latin American culture that even their fellow caravan members ostracized and abused them. Finally, in Mexico City, the LGBTQ community provided buses to the transgender members of the Caravan, to ensure their safety for the rest of the trip.

HG: What are the statistics/demographics of people in the Caravan (s)?

AT: Some estimate that there are as many as 14,000 members of the Migrant Caravan. Many say there are at least 5,000 to 7,000. The Mexican Government estimated that 2,800 minors were traveling with the Caravan when I joined them. The demographics were varied. From my observation, there were women, children, men, youth, seniors, families, and unaccompanied minors. As we went along, people dropped off the Caravan to seek asylum in Mexico. The Caravan was mostly formed by people from the Northern Triangle; an area made up of Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador.

HG: Please tell me some specific stories of these people that you spent time with? Why did they make their journeys?

AT: The life expectancy for trans women in El Salvador is 35 years, and there has been a 400% increase in the number of trans women murdered there since 2003. Many find it preferable to risk a dangerous excursion across thousands of miles for a chance at safety. The Maras (gangs) have taken over the Central American countries, threatened transgender people with death, and held young people hostage. That's why the Caravan had so many unaccompanied minors because children as young as 10 and 12 years old are forced to join the gangs. If they resist, they are murdered, so the parents send their children away in desperation to keep them safe.

During my journey, I heard several horrifying stories. I met a young girl, Alejandra, who had been raped by the federal police. She was traveling along with her brother, who lost an arm on the train and was unable to defend her. Because the train is for cargo, it often makes sudden stops that injure the migrants on board. La Bestia is known by locals as "The Train of Death" due to the multiple deaths and injuries suffered by those who have traveled on it. The guilt her brother felt was indescribable, along with the frustration that justice would not be served because it had been the police who had attacked her.

On one of my trips, I met Candida and her three children. Candida left her home country of Guatemala after she was raped. Her attackers threatened to rape her children as well. Candida escaped with her children and was allowed into the U.S. a week before the supreme court decision took effect that would have prevented her from entering.

Many families seeking asylum, including pregnant women, walk up to 10 hours at a time because they could not get rides. Children with special needs are not getting their proper medicine. We have a humanitarian crisis that needs to be addressed. Again, the idea is to open a space that increases awareness around the human rights violations of asylum-seekers. The work that I've been making over the past five years has touched me in a way that is hard to describe. I learned much about the hope and desperation people have faced in their journey towards a better life. I am aware that borders serve an essential purpose, but we need a humane immigration and asylum system.

HG: How are you still involved with this project?

AT: I have been documenting those seeking asylum at the US-Mexican Border in my hometown of Juarez, where the illegal practices of metering are taking place. People are facing horrible conditions in the detention centers of the U.S. and then being returned to Juarez, one of the most dangerous cities in the world, to wait for their asylum case. There are an estimated 18,000 people waiting to have their asylum claim heard by the US Government just in Juarez alone. Recently I have been focusing on the Shelters where the Caravan has been dispersed, and new members have arrived. The issues surrounding immigration are not going away any time soon, especially with the Trump Administration's unjust policies. I still keep in contact with many of the Caravan members I met, as well as the Minority Humanitarian Foundation, who helps them.

HG: How do you see this photography helping people that are seeking asylum?

AT: There are many misconceptions and rampant racism associated with the immigrants coming from Central and South America. My goal is to bring awareness to the faces and the stories of good, hardworking people that have had horrible experiences and have a legal right under the 1951 refugee convention to seek asylum.

Through all of my work, I hope that viewers here in the United States can begin to understand the odysseys many have undertaken to provide a brighter future for themselves and their children. The stories behind my photographs are both heartbreaking and complex, and they defy generalizations that seek to divide us. Through the lens of my camera, I hope to bring awareness and inform those who may have never been to the border and may not have ever met a refugee. Above all, I hope my art sparks conversations where there has been too much confusion and mistrust.

HG: Thank you for sharing your story and images.

AT: Thank you.